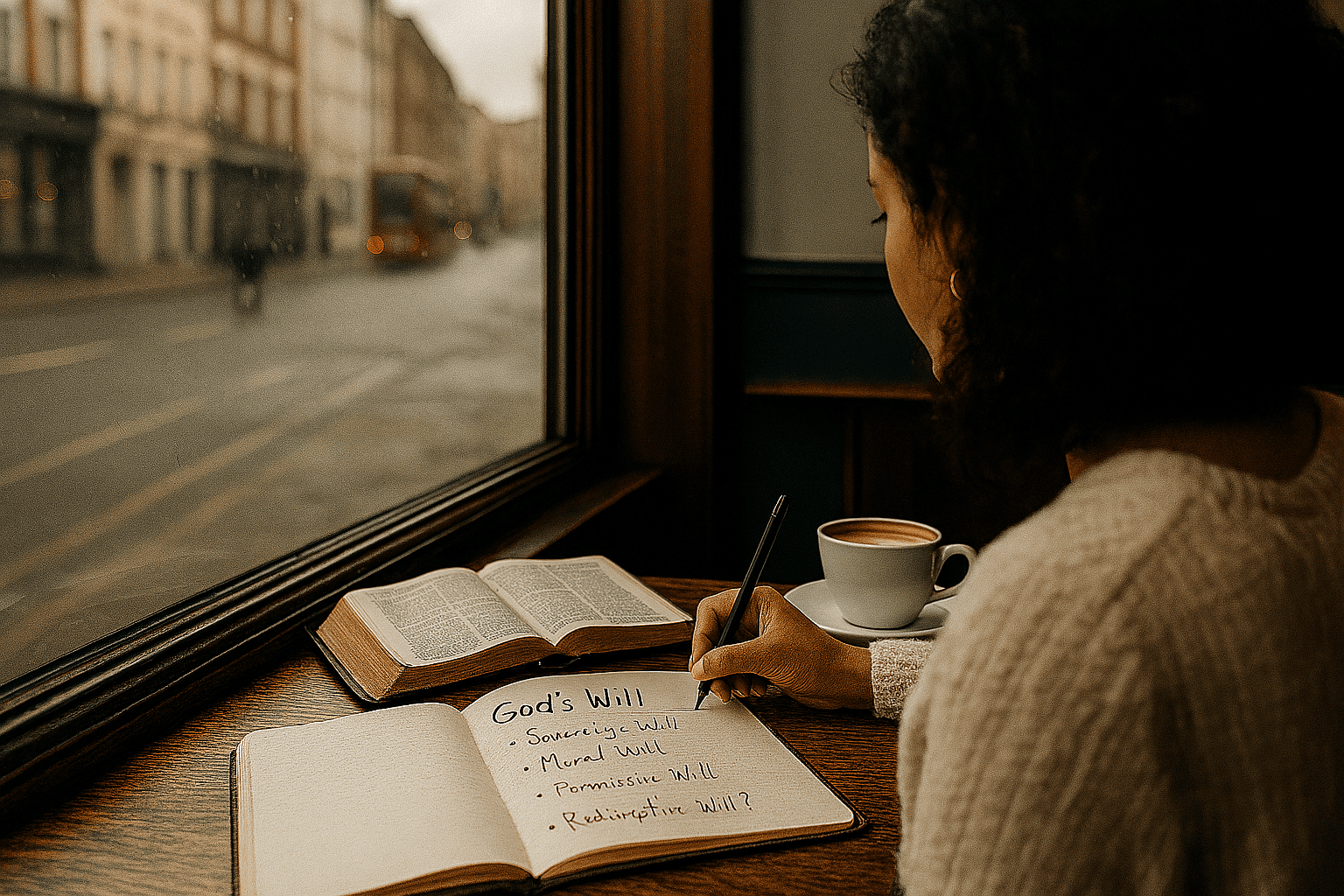

God’s will isn’t a single, monolithic thing.

For all its importance, “God’s will” remains one of the most misunderstood concepts in Christian thought. Believers wrestle with painful questions: If it’s God’s will, why pray? If God is sovereign, why obey? How can we “find” God’s will for our lives when Scripture seems silent on our specific decisions?

When Heaven’s Purpose Meets Earth

“Your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.”

— Matthew 6:10, ESV

When Jesus taught his disciples to pray these words, he was not offering a pious platitude or a resigned shrug toward fate. He was inviting them into the central drama of Scripture itself—the unfolding story of God’s will moving through history like a river, sometimes visible on the surface, sometimes running deep beneath human choices, always flowing toward a destined sea. From the garden command in Genesis to the restored city in Revelation, the Bible traces how God’s purposes govern the universe, how his commands shape human life, and how his redemptive plan transforms even rebellion into restoration.

Yet for all its importance, “God’s will” remains one of the most misunderstood concepts in Christian thought. Believers wrestle with painful questions: If it’s God’s will, why pray? If God is sovereign, why obey? How can we “find” God’s will for our lives when Scripture seems silent on our specific decisions? The confusion often stems from treating God’s will as a single, monolithic thing—a hidden blueprint to discover or a Devine determinism that cancels human choice. But the Bible itself speaks with greater nuance, revealing God’s will in several distinct yet harmonious ways. Understanding these distinctions doesn’t solve every mystery, but it does illuminate how prayer, obedience, suffering, and hope fit together in the life of faith. This is not abstract theology; it’s the grammar of trust.

The Foundations: God’s Will in Torah and Covenant

The Pentateuch—the five books of Moses—introduces God’s will primarily through two channels: sovereign promise and revealed command. In Genesis, God’s will operates as decree: “Let there be light” (Gen. 1:3), and light obeys. No negotiation, no resistance. This is God’s sovereign or decretive will, the aspect of his purpose that ordains outcomes and shapes the cosmos by sheer divine authority. The Hebrew word often translated “will” or “purpose” in these contexts is chephets (חֵפֶץ), denoting delight or desire—what God takes pleasure in accomplishing. When God calls Abram and promises, “I will make of you a great nation” (Gen. 12:2), he is not offering a conditional possibility but announcing a settled intention. History will bend toward this promise.

But Genesis also introduces a second dimension: human moral agency under God’s command. God permits Adam and Eve genuine choice, even the choice to rebel. This introduces what theologians call God’s permissive will—not what God endorses, but what he allows within the freedom he grants to creatures. Evil enters not because God wills it morally, but because he permits it within a world where love and obedience must be freely given to be meaningful. Joseph’s brothers sell him into slavery; God does not cause their treachery, yet Joseph later testifies, “You meant evil against me, but God meant it for good” (Gen. 50:20). The brothers act freely and culpably; God’s sovereign purpose absorbs their evil and redirects it toward salvation for many. This is the interplay that will echo throughout Scripture.

By Exodus, God’s will takes a third form: revealed law. At Sinai, Yahweh thunders from the mountain with commandments—Ten Words that express his moral character and govern Israel’s covenant life. “You shall have no other gods before me” (Ex. 20:3); “You shall not murder” (Ex. 20:13). This is God’s preceptive or moral will, the normative standard by which humans should live. It is not hidden or mysterious; it is carved in stone, repeated by Moses, written on scrolls. Deuteronomy 29:29 captures the distinction perfectly: “The secret things belong to the LORD our God, but the things that are revealed belong to us and to our children forever, that we may do all the words of this law.” God’s decrees may remain hidden until their time, but his moral will is disclosed so that obedience becomes possible.

Crucially, these laws are not arbitrary. They flow from God’s holy character and aim at human flourishing under his lordship. “You shall be holy, for I the LORD your God am holy” (Lev. 19:2). The moral will is the imprint of God’s nature on human conduct. To obey is not to earn God’s favor but to reflect his image, to live as his covenant people. And woven through all the statutes is a fourth strand: God’s redemptive will, his long-arc purpose to bless all nations through Abraham’s seed (Gen. 22:18). Law and promise together show a God who commands and a God who saves, whose will encompasses both “Thou shalt” and “I will.”

The Narrative Arc: God’s Will in Israel’s History

The Historical Books—Joshua through Esther—trace how God’s sovereign and moral will collide with human rebellion and faithfulness across generations. These narratives are not mere chronicles; they are theological dramas showing what happens when a people align with or reject God’s revealed will, and how God’s sovereign purposes press forward regardless.

In Judges, the refrain tolls like a funeral bell: “Everyone did what was right in his own eyes” (Judg. 21:25). Israel abandons the moral will of God, yet God permits this lawlessness—not because he approves, but because covenant relationship requires free response. Still, his redemptive will does not falter. He raises up deliverers, judges who embody his intervention in history. Even the flawed Samson, driven by lust and vengeance, becomes an instrument of God’s purpose to harass the Philistines (Judg. 14:4). God’s sovereign will incorporates even broken tools.

The books of Samuel and Kings present kingship as both gift and test. When Israel demands a king “like all the nations” (1 Sam. 8:5), they reject God’s direct rule—an affront to his moral will. Yet God grants their request, not as endorsement but as permission. Saul’s failure and David’s rise show that God’s sovereign election operates within, not against, human decisions and consequences. David, despite his adultery and murder, is called “a man after [God’s] own heart” (1 Sam. 13:14)—not because David never sinned, but because he aligned his deepest desires with God’s purposes and repented when he strayed. God’s will for Israel includes both judgment on sin (the death of David’s son, 2 Sam. 12:14) and preservation of the messianic line (the promise to David’s house, 2 Sam. 7:16). Sovereignty and morality, permission and purpose, interweave.

The Exile epitomizes this complexity. God’s moral will condemns idolatry, yet his permissive will allows Israel to chase foreign gods for centuries. His sovereign will decrees exile as judgment—announced beforehand through Moses (Deut. 28:64) and reiterated through the prophets. And within the catastrophe, his redemptive will ordains a return, a remnant, and ultimately a Messiah. Nehemiah prays, “Let your ear be attentive to the prayer of your servant… who delight to fear your name” (Neh. 1:11). To “delight to fear” is to align one’s desires with God’s moral will; to pray for restoration is to appeal to his redemptive purpose. The historical books thus become a tutorial in providence: God governs all, permits much, judges sin, and redeems those who return.

Wisdom and Worship: Seeking God’s Will in Daily Life

The Wisdom literature—Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Solomon—shifts from national epic to individual experience. Here the question is not “What is God doing in history?” but “How should I live rightly before him?” and “Where is God when I suffer?”

Proverbs presents God’s will as accessible wisdom for righteous living. “Trust in the LORD with all your heart, and do not lean on your own understanding. In all your ways acknowledge him, and he will make straight your paths” (Prov. 3:5–6). This is practical guidance rooted in the fear—reverence and awe—of Yahweh. Wisdom is not esoteric mysticism; it is skillful living according to God’s moral order. The wise person discerns what pleases God and acts accordingly: honesty over deceit, diligence over sloth, humility over pride. Wisdom literature democratizes the knowledge of God’s will—it is not reserved for priests or prophets but offered to all who listen.

Psalms adds a dimension of prayer and lament. The psalmists model how to seek alignment with God’s will even in darkness. “Teach me to do your will, for you are my God!” (Ps. 143:10). “I delight to do your will, O my God; your law is within my heart” (Ps. 40:8). These prayers breathe trust and desire—trust that God’s purposes are good, desire that one’s own life might conform to them. Yet the lament psalms also voice raw questions: “How long, O LORD?” (Ps. 13:1). They show that submission to God’s will is not passive fatalism but honest wrestling. God invites the questions even as he calls for surrender.

Job takes this tension to its extreme. Job is blameless, yet catastrophe befalls him. His friends insist suffering must be punishment, that God’s will is transparent and retributive. Job rejects this calculus; he knows he hasn’t earned his agony. Eventually God speaks from the whirlwind, not answering Job’s “Why?” but overwhelming him with the majesty of divine sovereignty: “Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth?” (Job 38:4). The message is not “Shut up and take it” but “Trust the one whose purposes span creation and exceed your comprehension.” Job’s restoration shows God’s redemptive will at work, but the book leaves mystery intact. Some aspects of God’s decretive will remain secret things (Deut. 29:29), known fully only to him.

The Prophets: God’s Will as Judgment and Promise

The Major and Minor Prophets thunder with God’s revealed will in the form of covenant lawsuit—indictments for breaking his commands—and eschatological promise—visions of his redemptive purposes fulfilled.

Isaiah captures both poles. “Cease to do evil, learn to do good; seek justice, correct oppression” (Isa. 1:16–17)—this is moral demand. Yet Isaiah also announces God’s sovereign plan: “My counsel shall stand, and I will accomplish all my purpose” (Isa. 46:10). The Hebrew word for “purpose” here is chephets (חֵפֶץ) again—God’s delight, his unshakable intent. Human kingdoms rise and fall under God’s governance; Cyrus, a pagan king, becomes God’s “anointed” to free Israel (Isa. 45:1), a stunning example of God’s sovereign will bending history to redemptive ends.

Jeremiah confronts a people who mistake God’s permissive will (allowing the temple to stand for a time) for unconditional endorsement. “Do not trust in these deceptive words: ‘This is the temple of the LORD’” (Jer. 7:4). God permits the temple’s existence provisionally, but his moral will demands justice and faithfulness. When these are absent, judgment comes—not arbitrarily, but as consequence woven into the covenant. Yet even in exile, God promises restoration: “‘I know the plans I have for you,’ declares the LORD, ‘plans for welfare and not for evil, to give you a future and a hope’” (Jer. 29:11). This verse, often wrested from context for personal comfort, is corporate and eschatological—God’s redemptive will for Israel will not be thwarted.

Ezekiel and Daniel add apocalyptic visions, pulling back the veil on cosmic warfare and divine sovereignty over empires. God’s will operates not just in Judah but among the nations; not just in the present but toward a future consummation. “I will vindicate the holiness of my great name… And the nations will know that I am the LORD” (Ezek. 36:23). This is teleological will—God’s purpose driving history toward a goal where his glory is revealed and creation is healed.

The Gospels: God’s Will Incarnate

In Jesus, God’s will moves from word to flesh. The Gospels present Christ as the ultimate expression of the Father’s will—in his teaching, his obedience, and his redemptive death.

The Lord’s Prayer, taught in Matthew 6, places “your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven” at the heart of Christian petition. Heaven is the realm where God’s will is perfectly enacted, without rebellion or delay. Jesus teaches his followers to pray that this reality would invade earth—that God’s moral will would be obeyed, that his redemptive purposes would advance, that his kingdom would come. It is a prayer of alignment, not resignation. “Thy will be done” does not mean “I guess I’ll accept whatever happens” but “May your righteous rule be established here and now.”

Jesus’ own life embodies this prayer. In Gethsemane, facing the cross, he prays, “My Father, if it be possible, let this cup pass from me; nevertheless, not as I will, but as you will” (Matt. 26:39). Here we see two wills—the human will of Jesus shrinking from suffering, and the divine will of the Father ordaining atonement. Jesus’ submission is not fatalism; it is the free, agonized choice to trust the Father’s redemptive purpose. Luke’s version adds, “Father, if you are willing, remove this cup from me. Nevertheless, not my will, but yours, be done” (Luke 22:42). The Son’s perfect obedience in the face of immeasurable cost reveals what it means for creatures to align with the Creator’s will.

The Synoptic Gospels also record Jesus’ teaching that knowing and doing God’s will is the family mark of his disciples. “Whoever does the will of my Father in heaven is my brother and sister and mother” (Matt. 12:50). Relationship with Christ is defined not by mere verbal confession but by obedient alignment with God’s revealed will. The Sermon on the Mount unpacks what this looks like: mercy, purity, peacemaking, love for enemies (Matt. 5–7). This is the moral will of God for kingdom citizens.

John’s Gospel introduces the language of God’s “work” and Jesus’ obedience to it. “My food is to do the will of him who sent me and to accomplish his work” (John 4:34). Jesus does not come as a rogue agent but as the sent one, perfectly executing the Father’s redemptive will. And at the cross, that will is accomplished: “It is finished” (John 19:30). The Greek word tetelestai (τετέλεσται) conveys completion, fulfillment. God’s sovereign plan to redeem humanity through the death and resurrection of his Son reaches its ordained climax.

The Epistles: Living in Light of God’s Will

Paul and the other apostolic writers unpack the implications of Christ’s finished work for Christian obedience and assurance. The Epistles give shape to both the moral and sovereign aspects of God’s will.

Romans 12:2 exhorts, “Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that by testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect.” Here God’s will is moral and discernible through Spirit-led transformation. It is not a cryptic puzzle but a knowable standard of holiness. Paul elaborates in 1 Thessalonians 4:3: “This is the will of God, your sanctification”—specifically, sexual purity and love. The moral will is concrete.

Yet Paul also grounds believers’ security in God’s sovereign will. “Those whom he predestined he also called, and those whom he called he also justified, and those whom he justified he also glorified” (Rom. 8:29–30). This golden chain of salvation reflects God’s decretive will, his eternal purpose to save a people for himself. Nothing can separate us from his love (Rom. 8:38–39) because our salvation rests not on our grip but on his. Ephesians 1:11 declares we were “predestined according to the purpose of him who works all things according to the counsel of his will.” The Greek word proorizo (predestined) (προορίζω) literally means “to mark out beforehand”—God’s will operates not as reaction but as eternal intention.

Suffering is reframed under this sovereign purpose. “We know that for those who love God all things work together for good, for those who are called according to his purpose” (Rom. 8:28). Paul does not say all things are good—tragedy, injustice, persecution are evils God permits—but that God’s redemptive will bends even these toward ultimate good for his children. This is providence: God’s wise and powerful governance ensuring his purposes prevail.

The pastoral epistles and Hebrews emphasize God’s will for communal life and perseverance. Hebrews 10:36 says, “You have need of endurance, so that when you have done the will of God you may receive what is promised.” Doing God’s will (obedience) and receiving the promise (inheritance) are linked, not as earning but as covenant relationship. And Hebrews 13:21 prays that God would “equip you with everything good that you may do his will, working in us that which is pleasing in his sight.” Here divine action and human response interlock—God works in us, we do his will.

Revelation: God’s Will Consummated

The Apocalypse of John brings the theme full circle. Revelation unveils—the Greek apokalypsis (ἀποκάλυψις) means uncovering—the final outworking of God’s sovereign and redemptive will. The scroll sealed with seven seals (Rev. 5) represents God’s decrees for history; only the Lamb who was slain can open it, showing that Jesus’ death is the hinge on which all divine purposes turn.

The visions of judgment are not arbitrary; they express God’s moral will vindicating justice. The prayers of the martyrs—“How long?” (Rev. 6:10)—echo the lament psalms, but here they receive answer. God’s permissive will allowed their suffering, but his sovereign will ensures their vindication. The fall of Babylon (Rev. 18) and the binding of Satan (Rev. 20) demonstrate that evil’s apparent victories are temporary permissions within a larger plan.

And then the consummation: “Behold, the dwelling place of God is with man. He will dwell with them, and they will be his people, and God himself will be with them as their God” (Rev. 21:3). The redemptive will announced in Genesis—God walking with his people—is fully realized. The new creation reflects God’s original purpose: a world where his will is done perfectly, where heaven and earth are one. The final “Amen. Come, Lord Jesus!” (Rev. 22:20) is the ultimate “Thy will be done.”

Returning to the Prayer

When Jesus taught, “Your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven,” he was not introducing a new idea but gathering up the entire scriptural witness into a single petition. He was inviting his disciples to pray that God’s sovereign purposes would triumph, that his moral commands would be obeyed, that his redemptive plan would advance, and that the brokenness he permits would one day be healed. It is a prayer of trust (“You are good and your purposes are wise”), of repentance (“Align my life with your ways”), and of hope (“Bring your kingdom fully”).

The four aspects of God’s will—sovereign, moral, permissive, redemptive—are not competing ideas but facets of the one divine character. God decrees the end from the beginning, yet invites human participation. He commands holiness, yet permits rebellion in a world where freedom makes love possible. He works all things toward redemption, absorbing even evil into a story of restoration. To pray “Thy will be done” is not to abandon discernment or responsibility; it is to entrust outcomes to the one who sees what we cannot, who holds what we cannot grasp, who loves with a constancy we cannot fathom.

This is no cold determinism. It is the heart of a Father who disciplines those he loves, who weeps over rebellion, who sent his Son to die for enemies, who invites his children to reason together (Isa. 1:18) and to make their requests known (Phil. 4:6). The God of Scripture has a will—settled, good, multifaceted—and he invites us not just to submit to it but to delight in it, to seek it, to pray for its full arrival on earth as it already reigns in heaven.

Editor’s Note: First, if you found yourself wanting more, we have explored these four types of God’s Will in a Series.

Second, If you’ve grown up hearing “finding God’s will” described like a scavenger hunt—one wrong turn and you’ve missed his perfect plan—this article offers freedom. God’s moral will isn’t hidden; it’s revealed in Scripture. You don’t need to agonize over whether to take Job A or Job B when both align with biblical wisdom and godly character. God delights in your sanctified freedom to choose wisely within his moral boundaries.

At the same time, resist the opposite error: treating God’s sovereignty as an excuse for passivity. “It’s all in God’s hands” can become a pious-sounding escape from obedience, prayer, or hard decisions. The Bible calls you to active trust—to seek wisdom, to pray fervently, to obey what’s clear, and to rest in what remains mysterious. God’s decrees don’t cancel your responsibility; they ground it.

So pray “Thy will be done” with both surrender and expectation. Surrender your demand to control outcomes; expect that the God who governs history invites you to participate in it. Read his Word to know his moral will. Trust his providence when circumstances confuse you. And keep praying for his kingdom to come—on earth, in your life, as it already reigns in heaven.