You meant evil.., but God meant it for good.

If God could prevent evil, why doesn’t he? How can he be good and all-powerful if he allows rape, genocide, child abuse, betrayal? Can we trust a God who permits what he does not approve?

Freedom, Evil, and Providence

This article is part of our Prayers Series—God’s will is not a puzzle to solve—it is a person to trust. This series explores four biblical dimensions: sovereign decrees, moral commands, permissive allowances, and redemptive purposes.

“As for you, you meant evil against me, but God meant it for good, to bring it about that many people should be kept alive, as they are today.”

— Genesis 50:20, ESV

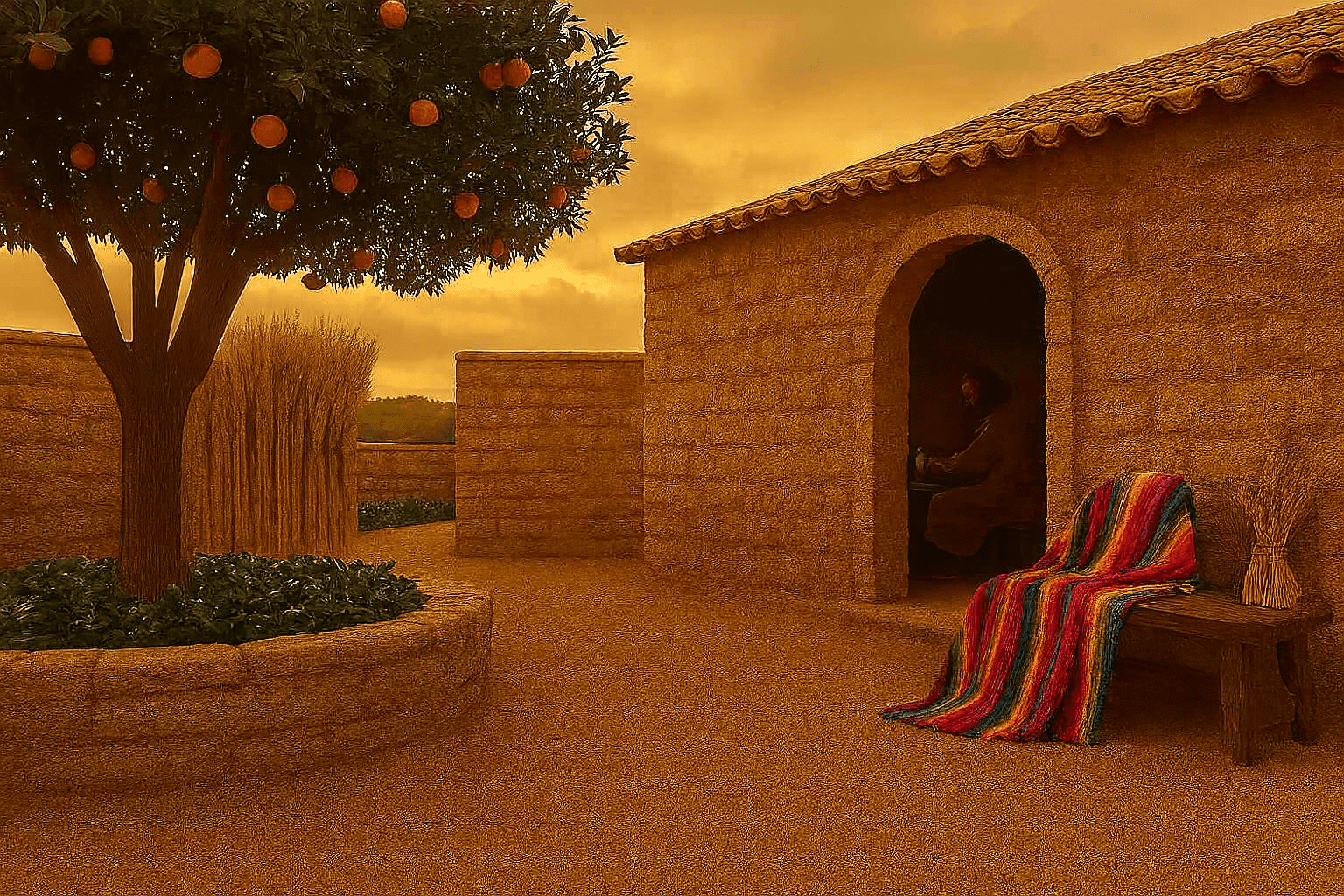

Joseph speaks these words to the brothers who betrayed him, sold him into slavery, and shattered his family. Twenty-two years have passed—years of false accusations, imprisonment, forgotten promises, and separation from his father. The brothers stand before him terrified, expecting vengeance. But Joseph sees something they cannot: a deeper story running beneath their treachery. They meant evil—the Hebrew verb chashav (חָשַׁב) conveys deliberate planning, intentional wickedness. Their choice was real, their guilt undeniable. Yet God meant it for good—the same verb, the same intentionality, but aimed toward a vastly different end. Two wills operating in the same event: human evil and divine purpose, neither canceling the other, both fully real.

This is the hardest dimension of God’s will to grasp—what theologians call his permissive will. God does not cause the brothers’ sin, does not approve their malice, does not endorse their betrayal. Yet he permits it. More than that, he governs it, sets its boundaries, and weaves it into a tapestry of redemption. The evil remains evil; the perpetrators remain guilty. But God’s sovereign authority ensures that no evil falls outside his control, and his redemptive purposes guarantee that no suffering is wasted. This is not an easy truth. It raises agonizing questions: If God could prevent evil, why doesn’t he? How can he be good and all-powerful if he allows rape, genocide, child abuse, betrayal? Can we trust a God who permits what he does not approve? This article will not resolve every mystery—Scripture itself guards some tensions without dissolving them—but it will trace what the Bible reveals about how God’s permission, human freedom, and divine providence intersect.

Examine the Biblical Foundation

The concept of God’s permissive will emerges as early as Genesis 3. God commands Adam not to eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (Gen. 2:17). This is God’s revealed, moral will—clear and explicit. Yet when the serpent tempts Eve and she eats, and Adam follows, God does not intervene to stop them. He permits the choice. He does not cause their sin—James 1:13 declares, “God cannot be tempted with evil, and he himself tempts no one”—but he allows it within the scope of creaturely freedom he has granted. The fall is not outside God’s sovereign governance (he knew it would happen and ordained the plan of redemption before the foundation of the world, Eph. 1:4), yet Adam and Eve are fully responsible. God’s permission does not equal causation or approval.

The consequences follow immediately: guilt, shame, broken relationships, pain in childbearing, toil in labor, death itself. These are not good. They are the wages of sin, the fracturing of a world meant to reflect God’s glory. But even here, in the darkest moment, God announces a redemptive purpose: “I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and her offspring; he shall bruise your head, and you shall bruise his heel” (Gen. 3:15). This is the protoevangelium—the first gospel—the promise that from the wreckage of human rebellion, God will bring a Redeemer. God permits the fall, but he does not permit it to be the final word.

Joseph’s story, quoted in the opening, is the clearest Old Testament example of God’s permissive will in action. His brothers’ sin is real—Genesis 37:18 says, “They saw him from afar, and before he came near to them they conspired against him to kill him.” Premeditated evil. God does not author this wickedness, but he permits it. And over the years in Egypt, God is at work beneath the surface. Joseph is sold to Potiphar; the Lord is with him, and he prospers (Gen. 39:2). He is falsely accused and imprisoned; the Lord is with him, and he finds favor (Gen. 39:21). He interprets dreams, saves Egypt from famine, and when the brothers arrive desperate for food, Joseph recognizes the thread: “God sent me before you to preserve life” (Gen. 45:5). Not “You sent me”—though they did. But “God sent me”—because God’s sovereign purpose governed even their evil intent. This is the mystery of permission: God does not commit evil, but he permits it and governs its outcomes for redemptive ends.

The Exodus introduces another layer. Pharaoh’s heart is hardened—but by whom? Sometimes Scripture says Pharaoh hardens his own heart (Ex. 8:15, 32; 9:34). Other times it says God hardens Pharaoh’s heart (Ex. 9:12; 10:20, 27; 14:8). Both are true. Pharaoh acts freely; his refusal to obey God is his own sin. Yet God’s sovereign will ordains that Pharaoh’s defiance will serve a larger purpose: “For this purpose I have raised you up, that I might show my power in you, and that my name might be proclaimed in all the earth” (Ex. 9:16, quoted in Rom. 9:17). God does not make Pharaoh wicked against his will; Pharaoh already is wicked. God permits Pharaoh’s rebellion and governs it to display both justice and mercy—judgment on Egypt, salvation for Israel.

Job’s suffering presents perhaps the most intense wrestling with God’s permissive will in all of Scripture. Satan accuses Job of serving God only for blessings, and God permits Satan to test him—first taking his wealth and children (Job 1:12), then afflicting his body with sores (Job 2:6). Job’s suffering is not caused by God directly; it is inflicted by Satan. Yet it happens only within the boundaries God sets: “Behold, all that he has is in your hand. Only against him do not stretch out your hand” (Job 1:12). Permission with limits. Satan is the active agent of harm; God is the sovereign authority who permits and governs.

Job’s friends insist there must be hidden sin—suffering is always punishment. But the narrator has already told us Job is blameless (Job 1:1). Job protests his innocence and demands answers, but God does not explain. Instead, God confronts Job with a series of questions: “Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth?” (Job 38:4). God does not say, “I allowed your suffering because…” He says, “Trust the one who governs the cosmos.” Job’s response is not resignation but worship: “I know that you can do all things, and that no purpose of yours can be thwarted” (Job 42:2). He trusts God’s sovereignty even when he doesn’t understand God’s purposes. In the end, God restores Job (Job 42:10), but the book leaves the tension unresolved: God permits suffering we do not deserve, for reasons he may not disclose, yet he remains sovereign and good.

The crucifixion is the climax of how God’s permissive will operates. Wicked men—Herod, Pilate, Gentile soldiers, the Jewish leaders—conspire to murder the sinless Son of God. This is evil, a violation of God’s moral will: “You shall not murder” (Ex. 20:13). Yet Peter preaches, “This Jesus, delivered up according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God, you crucified and killed by the hands of lawless men” (Acts 2:23). The Greek phrase “definite plan” is hōrismenē boulē (ὡρισμένῃ βουλῇ)—a determined counsel, a fixed purpose. God ordained the crucifixion. The early church prays, “Truly in this city there were gathered together against your holy servant Jesus, whom you anointed, both Herod and Pontius Pilate, along with the Gentiles and the peoples of Israel, to do whatever your hand and your plan had predestined to take place” (Acts 4:27–28). The most heinous evil in history—deicide, the murder of God—was predestined by God. Yet the human actors remain fully culpable. God did not make them sin; he permitted their free, wicked choices and governed them to accomplish the atonement.

Here is the heart of the matter: if God can take the worst evil—the cross—and turn it into the greatest good—the salvation of sinners—then no evil is beyond his governance, and no suffering is outside his redemptive purposes. This does not make evil good. It does not remove human guilt. But it anchors hope: the God who permitted the crucifixion and brought resurrection can be trusted with every other suffering we endure.

Paul’s thorn in the flesh illustrates how God’s permissive will operates in personal suffering. Paul writes, “A thorn was given me in the flesh, a messenger of Satan to harass me, to keep me from becoming conceited” (2 Cor. 12:7). The thorn is from Satan—an affliction, not a blessing. Yet it is given—passive voice, implying God’s permission. Paul pleads three times for its removal, but God answers, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness” (2 Cor. 12:9). God permits the thorn, refuses to remove it, and uses it to display his power and keep Paul humble. Paul concludes, “For the sake of Christ, then, I am content with weaknesses, insults, hardships, persecutions, and calamities. For when I am weak, then I am strong” (2 Cor. 12:10). God’s permissive will allows suffering that he could prevent, yet his grace is present in it, and his purposes are accomplished through it.

Finally, Romans 8:28 offers the New Testament’s most comprehensive statement on how God’s sovereign and permissive wills relate: “We know that for those who love God all things work together for good, for those who are called according to his purpose.” The Greek verb synergei (συνεργεῖ), translated “work together,” means to cooperate, to function jointly toward an end. God does not say all things are good—cancer, abuse, betrayal, injustice are evils God permits but does not endorse. But God does promise that all things—even evils—will be woven together for good for his children. This is not wishful thinking or pious platitude. It is covenant promise grounded in God’s sovereign control and redemptive purposes.

Clarify Key Distinctions

God’s permissive will must be carefully distinguished from his moral will and his sovereign will. His moral will reveals what he commands and approves; his permissive will includes what he allows but does not approve. Murder violates God’s moral will, yet God permits murder—Cain kills Abel, the brothers plot against Joseph, Herod kills the innocents, the mob crucifies Jesus. In each case, God could prevent the evil but does not. His permission is not passive indifference; it is active governance within boundaries he sets. He permits the evil to occur, governs its scope, and ensures it will serve his larger purposes.

God’s sovereign will ordains what comes to pass; his permissive will is part of that sovereign decree. God does not ordain some things (the good) while merely tolerating others (the evil). He ordains that certain evils will be permitted. This is crucial: permission itself is decreed. God does not lose control when sin happens; he has sovereignly determined to allow creaturely freedom, including the freedom to rebel. Why? Because love, trust, and obedience are meaningless unless freely given. A programmed robot cannot love; a coerced servant cannot trust. God permits sin not because he lacks power to prevent it but because a world with free creatures—even fallen, rebellious ones—better serves his purposes than a world of automatons.

Second, God’s permission does not imply causation. When Joseph says, “God sent me before you” (Gen. 45:5), he does not mean God made the brothers sin. God did not inject malice into their hearts, twist their arms, or override their wills. They chose freely and wickedly. Yet God’s sovereign purpose encompassed their choice and directed its outcome. Theologians call this concurrence—God’s will and human will operate concurrently, neither collapsing into the other. God governs all things, yet humans act freely. God ordains outcomes, yet humans bear responsibility for their choices. This is mystery, not contradiction. We may not comprehend how it works, but Scripture insists on both.

Third, permission is not the same as approval. God permits divorce (Deut. 24:1), but Jesus says, “From the beginning it was not so” and calls it a concession to human hard-heartedness (Matt. 19:8). God permits polygamy in the Old Testament (Abraham, Jacob, David, Solomon), but it always brings heartache and never reflects his creational ideal of one man, one woman (Gen. 2:24). God permits injustice, oppression, idolatry—he does not immediately strike down every evildoer—but he hates these things (Prov. 6:16–19; Amos 5:21–24). Permission is God’s decision, within his sovereign will, not to prevent something his moral will condemns. Why he permits some evils and not others is part of the “secret things” (Deut. 29:29) that belong to him alone.

Fourth, God’s permission operates within the scope of compatibilism—the biblical teaching that divine sovereignty and human responsibility are compatible. Pharaoh hardens his heart; God hardens Pharaoh’s heart. Both are true. The brothers betray Joseph; God sends Joseph ahead. Both are true. Wicked men crucify Jesus; God ordains the crucifixion. Both are true. This is not double-talk; it is the Bible’s consistent testimony that God’s sovereign will includes human agency as a secondary cause. The philosophical conundrum—”If God ordains it, how can humans be responsible?”—is not resolved in Scripture, but both truths are affirmed. The alternative is either to deny God’s sovereignty (making him a helpless observer) or to deny human responsibility (making humans puppets). Scripture rejects both extremes.

Finally, God’s permissive will is always purposeful. He does not permit evil arbitrarily or randomly. Every evil he allows serves his broader purposes: to reveal his character (justice in judgment, mercy in salvation), to accomplish his redemptive plan (the cross), to sanctify his people (suffering produces endurance, character, hope—Rom. 5:3–4), or to bring him greater glory. This does not mean we always see the purpose. Job never learned why he suffered. Paul never got the thorn removed. But the promise of Romans 8:28 stands: God works all things—including the things he permits but does not cause—for the good of those who love him.

Address Common Confusion

The doctrine of God’s permissive will raises the problem of evil in its most acute form: If God is all-powerful and all-good, why does evil exist? If he can prevent suffering, why doesn’t he? Philosophers call this the theodicy question—from the Greek theos (God) and dikē (justice)—the defense of God’s goodness in light of evil.

One common but inadequate response is to limit God’s power: “God’s hands are tied; he can’t prevent evil without violating human freedom.” But this denies Scripture’s clear teaching that God is sovereign over all things, including human choices. God does not merely react to what creatures do; he governs what they do. Another inadequate response is to deny that evil is truly evil: “Everything happens for a reason, so it’s all part of God’s good plan.” But this sanitizes suffering, minimizes sin, and can lead to victim-blaming. Cancer is not good. Abuse is not good. Betrayal is not good. These are evils God permits, not goods God designs.

The Bible’s answer to the problem of evil is not a philosophical argument but a historical event: the cross. At the cross, we see the worst evil—deicide—permitted, even ordained, by God, yet accomplishing the greatest good—redemption. God does not explain every evil, but he demonstrates that he can take the worst evil and turn it into salvation. If God can do that with the cross, we can trust him with every other evil. Romans 8:32 reasons, “He who did not spare his own Son but gave him up for us all, how will he not also with him graciously give us all things?” The cross is God’s theodicy. He proves his goodness not by preventing all suffering but by entering into it, bearing it, and redeeming through it.

A second confusion concerns the pastoral application of God’s permissive will. Some Christians misuse this doctrine to explain suffering in ways that add to the hurt: “God gave you cancer to teach you a lesson.” “Your child died because God needed another angel.” “This tragedy is God’s judgment on your secret sin.” These statements may reflect a twisted understanding of God’s permissive will, but they contradict Scripture. God does not author evil (James 1:13). He does not tempt anyone to sin. He does not delight in the death of the wicked (Ezek. 33:11). While God permits suffering and can use it for good, we must not glibly attribute evil directly to God’s active will as though he were the immediate cause.

Job’s friends made this mistake. They assumed suffering always equals divine punishment for specific sin. But the narrator told us Job was blameless. The friends’ theology was too neat, their categories too small. God rebukes them: “You have not spoken of me what is right, as my servant Job has” (Job 42:7). Job’s anguished questions and raw laments were more faithful than the friends’ tidy explanations. The lesson: it is better to sit in the mystery, lament the pain, and trust God’s character than to offer glib answers that misrepresent him.

A third confusion is the conclusion that if God permits evil, then evil must not be that bad. But Scripture never draws this inference. God permits evil within his sovereign purposes, yet he hates it, judges it, and will one day eradicate it. The fact that God permits sin does not minimize its wickedness or remove human guilt. Joseph’s brothers are culpable for their betrayal, even though God used it for good. Judas is guilty of treachery, even though his betrayal fulfilled God’s plan (Matt. 26:24). The Roman soldiers sinned in crucifying Jesus, even though the crucifixion was ordained. God’s permissive will allows evil to occur, but it does not make evil less evil or sinners less responsible.

Finally, some struggle with the tension itself: “How can God be sovereign over evil without being responsible for it?” This is where we must acknowledge mystery. Deuteronomy 29:29 reminds us that “the secret things belong to the LORD our God.” We do not have exhaustive knowledge of how God’s sovereignty and human responsibility intersect. We see both affirmed in Scripture—God’s decrees and human choices, divine permission and creaturely guilt—but we are not given a philosophical explanation that resolves every tension. Our calling is not to solve the mystery but to trust the God who holds it, who has proven his goodness at the cross, and who promises to work all things for the good of those who love him.

Provide Practical Wisdom

How does understanding God’s permissive will shape the way we pray, especially in suffering? First, it gives us permission to lament. If evil is real—not sanitized, not excused—then honest grief is appropriate. The Psalms are full of raw cries: “How long, O LORD? Will you forget me forever?” (Ps. 13:1). “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Ps. 22:1). Jesus himself prayed in agony, “Let this cup pass from me” (Matt. 26:39). God invites these prayers. He does not require stoic acceptance or pious platitudes. Lament is faith crying out to God in the midst of what should not be.

Second, it grounds intercession. We pray for God to intervene, to heal, to deliver, to prevent harm—because we know he can. His permissive will means he allows suffering, but his sovereign will means he can stop it. So we ask. We plead. We appeal to his mercy, his power, his promises. Paul prayed three times for the thorn to be removed (2 Cor. 12:8). Jesus prayed for the cup to pass (Matt. 26:39). Neither prayer was answered as requested, but both were faithful. We pray knowing God permits suffering, yet trusting he can and sometimes does intervene.

Third, it enables surrender. After praying for deliverance, we pray, “Nevertheless, not my will, but yours, be done” (Luke 22:42). This is not fatalism; it is trust. We entrust outcomes to the God who governs all things, who is wiser than we are, and whose purposes are good even when we cannot see them. Surrender does not mean we stop caring or praying; it means we rest in God’s sovereignty even when he permits what we wish he would prevent.

Fourth, understanding God’s permissive will shapes how we respond to evil done against us. Joseph could forgive his brothers because he saw God’s hand in the story: “You meant evil against me, but God meant it for good” (Gen. 50:20). This does not erase the brothers’ guilt or minimize the pain, but it reframes the suffering within God’s larger purposes. When we trust that God permits nothing outside his control and works even evil for good, we are freed from bitterness. We can forgive those who wrong us because we know God will judge justly and use even their sin redemptively.

Fifth, it provides hope in suffering. Romans 5:3–4 says, “We rejoice in our sufferings, knowing that suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope.” God permits suffering, but he does not waste it. He uses it to refine, sanctify, and mature his children. James 1:2–4 echoes this: “Count it all joy, my brothers, when you meet trials of various kinds, for you know that the testing of your faith produces steadfastness.” God’s permissive will means suffering will come; God’s redemptive purposes mean suffering will serve good ends.

Sixth, it guards us from presumption. We cannot always discern why God permits specific evils. Job never learned why he suffered. We may never know in this life why a loved one died, why a marriage ended, why a child was harmed. The “secret things belong to the LORD” (Deut. 29:29). Our calling is not to explain every suffering but to trust the God who governs it. Sometimes the most faithful response is, “I don’t know why, but I trust you.”

Finally, God’s permissive will shapes how we think about justice. God permits evil in this age, but he will judge it in the age to come. Revelation 6:10 records the martyrs crying out, “O Sovereign Lord, holy and true, how long before you will judge and avenge our blood?” God’s answer is not immediate vengeance but patience: “Rest a little longer, until the number of their fellow servants and their brothers should be complete” (Rev. 6:11). God permits injustice now, but he will right every wrong at the final judgment. This gives us patience to endure and confidence that justice will prevail.

Returning to Joseph’s Testimony

When Joseph declared, “You meant evil against me, but God meant it for good,” he was not minimizing his brothers’ sin or pretending the years of suffering were easy. He was testifying to a truth he had learned through two decades of anguish: God’s purposes run deeper than human malice. The brothers acted freely, wickedly, culpably. Yet God’s sovereign hand governed every step—the pit, the slave caravan, Potiphar’s house, the prison, Pharaoh’s court, the famine, the reunion. None of it was accidental. None of it was outside God’s control. And all of it served a purpose larger than Joseph could have imagined: “to bring it about that many people should be kept alive, as they are today” (Gen. 50:20).

This is the mystery and the comfort of God’s permissive will. He permits what he does not approve. He governs what he does not cause. He weaves even evil into a story of redemption. The evil remains evil; God hates it, judges it, and will one day eradicate it. But in the meantime, in this broken world where God has granted creatures the freedom to rebel, his sovereignty ensures that no suffering is meaningless, no evil is beyond his reach, and no purpose of his can be thwarted.

We may not understand why God permits specific evils. We may wrestle, like Job, with the silence. We may cry out, like the psalmists, “How long?” But we anchor our trust not in explanations but in the character of the God who permitted the worst evil—the crucifixion of his Son—and brought from it the greatest good—the salvation of sinners. If God can do that, he can be trusted with every other suffering. His permissive will is not arbitrary, not capricious, not cruel. It is the will of a sovereign God whose purposes are wise, whose heart is good, and whose ultimate aim is the display of his glory and the joy of his people. And one day, when all is revealed, we will see that even the darkest threads were woven into a tapestry more beautiful than we could have imagined.

Editor’s Note: If you’ve suffered deeply and struggled with the question “Where was God?” this doctrine may feel cold, even offensive. How dare we say God permitted this? But consider the alternative: a God who is helpless, who watches evil unfold but cannot govern it, who hopes things work out but cannot ensure they do. That God offers no comfort. He is as victimized by evil as we are.

The God of Scripture is different. He is sovereign over all things, including the evils he permits. This does not make him the author of evil—Scripture emphatically denies that (James 1:13). But it does mean that nothing happens outside his control, and nothing he permits is beyond his redemptive purposes. The cross proves this. The worst evil in history—the murder of the sinless Son of God—was ordained by God (Acts 4:27–28), yet it accomplished the greatest good—redemption for sinners. If God can take the cross and turn it into salvation, he can take your suffering and weave it into a story of grace.

This is not an answer to every “Why?” It is an anchor in the storm. God is sovereign. God is good. And the God who permitted the cross—and brought resurrection—can be trusted with your pain. Lament honestly. Question boldly. But do not let go of the God whose permissive will is always purposeful, whose sovereign will is always good, and whose redemptive will ensures that one day, all will be made new.