The Telos—the end goal

God’s will ensures it will happen, moral will describes the character of those being redeemed, permissive will allows the brokenness that makes redemption necessary. But God’s redemptive will is the through-line purpose that makes sense of the whole story.

The Purpose That Restores All Things

This article is part of our God’s Will Series—God’s will is not a puzzle to solve—it is a person to trust. This series explores four biblical dimensions: sovereign decrees, moral commands, permissive allowances, and redemptive purposes

“As a plan for the fullness of time, to unite all things in him, things in heaven and things on earth.”

— Ephesians 1:10, ESV

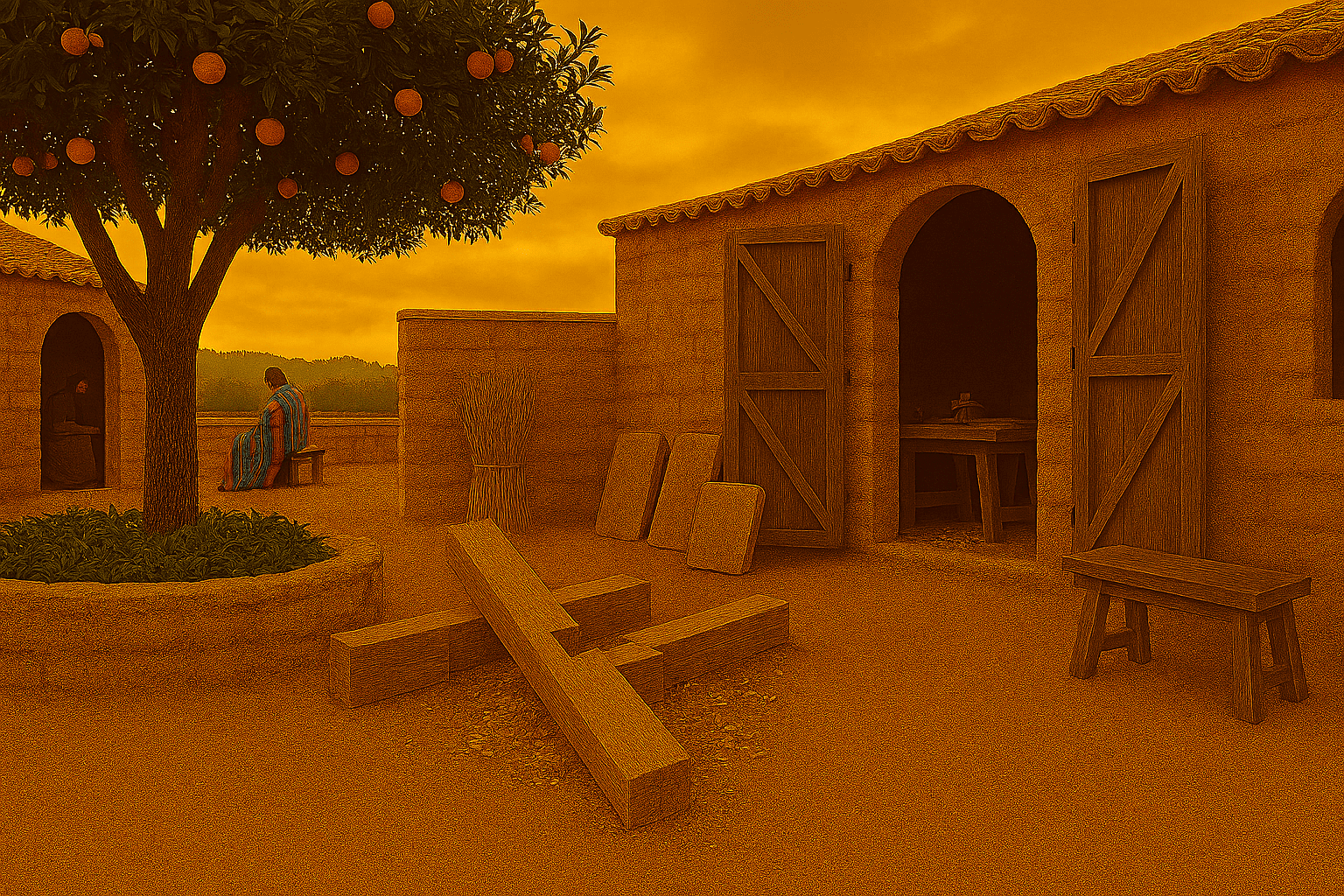

Paul unveils here what he calls a mystery—the Greek word mystērion (μυστήριον) refers not to something inherently incomprehensible but to something previously hidden and now revealed. For ages, God’s ultimate purpose remained veiled, hinted at in promises and prophecies but not fully disclosed. Now, in Christ, the curtain is pulled back and the plan is announced: God is bringing all things together under one head, reconciling heaven and earth, healing the fractures of the fall, restoring what sin has broken. This is not peripheral to God’s will; it is the telos—the goal, the destination, the end toward which everything else points. God’s sovereign decrees ensure it will happen. God’s moral commands describe the character of those being redeemed. God’s permissive will allows the brokenness that makes redemption necessary. But God’s redemptive will is the through-line purpose that makes sense of the whole story: God is remaking creation, and he is doing it through Christ.

This is not wishful thinking or human optimism. It is divine intention, announced in Genesis 3, accomplished at the cross, applied by the Spirit, and awaiting consummation when Christ returns. From the protoevangelium—the first gospel promise that the serpent’s head would be crushed—to the final vision of a new heaven and new earth where God dwells with his people, the Bible is one long story of redemption. And the protagonist is not humanity clawing its way back to God, but God himself pursuing, purchasing, and perfecting a people for his glory. This article traces God’s redemptive will across the canon, showing how it shapes history, hope, mission, and perseverance.

Examine the Biblical Foundation

The Bible’s first hint of redemption comes in the garden, moments after the fall. God does not abandon his image-bearers to their sin. Instead, he announces judgment on the serpent and a promise to humanity: “I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and her offspring; he shall bruise your head, and you shall bruise his heel” (Gen. 3:15). This is the protoevangelium—the first gospel—veiled in mystery but stunning in scope. One day, a descendant of the woman will crush the serpent, though it will cost him a wound. Sin has entered, but redemption is already decreed. God’s redemptive will is not a reaction to the fall; it was planned “before the foundation of the world” (Eph. 1:4). The fall does not surprise God or derail his purposes. It becomes the stage on which his glory in redemption will shine all the brighter.

God’s redemptive will takes covenantal form with Abraham. “I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and him who dishonors you I will curse, and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed” (Gen. 12:2–3). Notice the scope: all the families of the earth. God’s purpose is not merely to save one man or one nation but to bring blessing—salvation—to all peoples. This is teleological will—will aimed at a goal. The goal is universal blessing through Abraham’s seed, ultimately fulfilled in Christ (Gal. 3:16). Every promise, every patriarch, every twist in the narrative serves this redemptive trajectory.

The Exodus becomes the paradigmatic redemption event of the Old Testament. Israel is enslaved in Egypt, powerless to save themselves. God hears their groaning and remembers his covenant (Ex. 2:24). Then he acts: plagues, Passover, Red Sea crossing, covenant at Sinai. The Hebrew word for “redeem” is ga’al (גָּאַל), which means to buy back, to ransom, to act as kinsman-redeemer. God redeems Israel not because they deserve it but because of his covenant faithfulness and his commitment to his redemptive purposes. Exodus 6:6–7 declares, “I will redeem you with an outstretched arm and with great acts of judgment. I will take you to be my people, and I will be your God.” This is God’s redemptive will in action: deliverance from bondage, formation of a people, relationship with their God.

But Israel’s redemption from Egypt is not the ultimate goal; it points forward. The prophets announce a new covenant, a new exodus, a greater redemption. Jeremiah prophesies, “Behold, the days are coming, declares the LORD, when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and the house of Judah… I will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts. And I will be their God, and they shall be my people” (Jer. 31:31, 33). This is not merely external law but internal transformation—redemption that changes the heart. Ezekiel adds, “I will give you a new heart, and a new spirit I will put within you. And I will remove the heart of stone from your flesh and give you a heart of flesh” (Ezek. 36:26). God’s redemptive will includes not just forgiveness of sins but the renewal of human nature itself.

Isaiah paints the most expansive vision of God’s redemptive purposes. The Servant Songs (Isa. 42, 49, 50, 52–53) speak of one who will bring justice to the nations, be a light to the Gentiles, and bear the sins of many. “He was pierced for our transgressions; he was crushed for our iniquities; upon him was the chastisement that brought us peace, and with his wounds we are healed” (Isa. 53:5). This is vicarious atonement—the Servant suffers in the place of sinners. And the result is not just individual salvation but cosmic restoration: “For behold, I create new heavens and a new earth, and the former things shall not be remembered or come into mind” (Isa. 65:17). God’s redemptive will culminates in new creation, where death, mourning, crying, and pain are no more (Isa. 65:19; cf. Rev. 21:4).

In the Gospels, Jesus announces that God’s redemptive will has arrived in him. “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand; repent and believe in the gospel” (Mark 1:15). Jesus is the seed of the woman who crushes the serpent (Gen. 3:15), the seed of Abraham through whom all nations are blessed (Gen. 12:3; Gal. 3:16), the suffering Servant who bears our sins (Isa. 53; 1 Pet. 2:24), the Davidic King whose kingdom has no end (2 Sam. 7:16; Luke 1:33). His miracles—healing the sick, casting out demons, raising the dead, calming storms—are not mere displays of power but signs that God’s redemptive purposes are invading the broken world. Where Jesus is, the kingdom breaks in.

The cross is the hinge of redemption. Jesus declares, “The Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many” (Mark 10:45). The Greek word for “ransom” is lytron (λύτρον), a price paid to free captives. Jesus’ death is the payment that secures redemption. “In him we have redemption through his blood, the forgiveness of our trespasses, according to the riches of his grace” (Eph. 1:7). This is substitutionary atonement—Christ dies in the place of sinners, bearing the wrath they deserve, so they can receive the righteousness he earned. And his resurrection is the firstfruits of new creation, the guarantee that God’s redemptive will includes not just souls but bodies, not just individuals but the cosmos itself (1 Cor. 15:20–23; Rom. 8:21–23).

Paul’s letters unpack the scope of redemption. Ephesians 1:9–10 speaks of God’s purpose “to unite all things in him, things in heaven and things on earth.” The Greek word for “unite” is anakephalaiōsasthai (ἀνακεφαλαιώσασθαι), from anakephalaioō, meaning to sum up, to bring together under one head. All of history is moving toward Christ as the center, the head, the unifying point. Colossians 1:19–20 adds, “In him all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell, and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, making peace by the blood of his cross.” The scope is cosmic: all things. Christ’s redemptive work extends to every corner of creation fractured by sin.

Romans 8:18–25 describes creation itself groaning, waiting for redemption. “The creation was subjected to futility, not willingly, but because of him who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to corruption and obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God” (Rom. 8:20–21). God’s redemptive will includes the material world. The new heavens and new earth are not ethereal, disembodied existence but renewed physicality—resurrected bodies dwelling in a restored cosmos. Redemption is not escape from creation but the restoration of it.

The book of Revelation brings the story full circle. What was lost in Genesis 3 is regained in Revelation 21–22. The tree of life, barred after the fall (Gen. 3:24), reappears for the healing of the nations (Rev. 22:2). The curse is removed (Rev. 22:3). God dwells with his people as he did in the garden (Rev. 21:3). Death, mourning, crying, and pain—consequences of sin—are abolished (Rev. 21:4). And the cry goes up, “Behold, I am making all things new” (Rev. 21:5). Not some things. Not just spiritual things. All things. This is the consummation of God’s redemptive will: the complete renewal of heaven and earth, the marriage of the Lamb and his bride, the eternal joy of redeemed humanity in the presence of God.

Clarify Key Distinctions

God’s redemptive will is the overarching purpose that gives shape and direction to the other dimensions of his will. His sovereign will ensures redemption will happen—no power in heaven or earth can thwart it. His moral will describes the character of redeemed people and the life they are called to live. His permissive will allows the brokenness and evil that make redemption necessary. But his redemptive will is the goal toward which all history moves: the restoration of creation and the glory of God in the salvation of his people.

Second, God’s redemptive will is both particular and universal. It is particular in that God redeems a specific people—those chosen in Christ before the foundation of the world (Eph. 1:4), those given to the Son by the Father (John 6:37), those who believe and are saved (John 3:16). Not everyone will be saved; Jesus speaks of those who enter through the narrow gate and those who take the broad road to destruction (Matt. 7:13–14). Yet God’s redemptive purposes have universal scope: “All the families of the earth shall be blessed” (Gen. 12:3); “All things” will be reconciled (Col. 1:20); “Every knee will bow” (Phil. 2:10–11). The elect are drawn from every tribe, tongue, people, and nation (Rev. 5:9). Creation itself will be renewed (Rom. 8:21). Redemption is not universal in the sense that all individuals are saved, but it is cosmic in the sense that all things broken by sin will be restored.

Third, God’s redemptive will operates in an “already/not yet” tension. The kingdom has come in Christ (Luke 17:21); redemption is accomplished at the cross (John 19:30); believers are already raised with Christ and seated in heavenly places (Eph. 2:6). Yet the kingdom is still awaited in its fullness (Matt. 6:10); creation still groans (Rom. 8:22); we await the resurrection of the body and the new creation (1 Cor. 15:42–44; 2 Pet. 3:13). We live between the decisive victory (D-Day) and the final consummation (V-Day). God’s redemptive purposes are certain, but their full manifestation is future.

Fourth, God’s redemptive will includes both salvation from and salvation to. We are saved from sin, wrath, death, and condemnation (Rom. 5:9; 1 Thess. 1:10; Col. 1:13). But redemption is not merely escape; it is restoration. We are saved to holiness, eternal life, new creation, and joy in God’s presence (1 Thess. 4:3; Titus 1:2; Rev. 21:3–4). Redemption is not just forgiveness but transformation, not just pardon but adoption, not just rescue but renewal. God’s purpose is not merely to fix what sin broke but to bring his people into greater glory than Adam ever knew—the glory of knowing Christ and being conformed to his image (Rom. 8:29; 2 Cor. 3:18).

Finally, God’s redemptive will glorifies God. The ultimate purpose of redemption is not human happiness (though that is a fruit) but the display of God’s glory. Ephesians 1:6 says we are chosen “to the praise of his glorious grace.” Ephesians 1:12 says we are predestined “to the praise of his glory.” Ephesians 1:14 says the Spirit seals us “to the praise of his glory.” Three times in six verses, Paul anchors redemption in the purpose of God’s glory. This is not divine narcissism; it is the fitting end of all things. God is infinitely glorious, and creation’s highest joy is to see, savor, and proclaim that glory forever. Redemption brings us into that joy.

Address Common Confusion

One common confusion is universalism—the belief that God’s redemptive will includes the salvation of every individual. Passages like Colossians 1:20 (“to reconcile to himself all things“) and 1 Timothy 2:4 (“God desires all people to be saved”) are cited as proof. But Scripture elsewhere clearly teaches that not all will be saved. Jesus speaks of those who will hear, “I never knew you; depart from me” (Matt. 7:23). Revelation describes the lake of fire where the devil, the beast, the false prophet, and all whose names are not in the book of life will be thrown (Rev. 20:10, 15). When Paul speaks of reconciling “all things,” he means all things in the category of what God redeems—creation, the church, the cosmos fractured by sin—not every individual human. God’s redemptive will is universal in scope (cosmic) but particular in application (the elect).

A second confusion is hyper-realized eschatology—the belief that God’s redemptive purposes are fully accomplished now, that the kingdom has fully come, and believers should experience complete victory, health, and prosperity in this age. But Scripture maintains the “already/not yet” tension. Yes, we are new creations (2 Cor. 5:17). But we still groan, awaiting the redemption of our bodies (Rom. 8:23). Yes, Christ has defeated sin and death (1 Cor. 15:54–57). But death is still the last enemy to be destroyed (1 Cor. 15:26). Yes, healing and miracles accompany the kingdom (Luke 9:1–2). But Paul’s thorn remained, Epaphroditus nearly died, and Timothy had stomach ailments (2 Cor. 12:7–9; Phil. 2:27; 1 Tim. 5:23). The fullness of redemption awaits Christ’s return.

A third confusion is the opposite error—hyper-futurism or escapism, the belief that redemption is entirely future and has no present implications. Some Christians focus so much on “going to heaven when I die” that they neglect the already-inaugurated kingdom. But Jesus taught his disciples to pray, “Your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven” (Matt. 6:10). Redemption includes the here and now. We are already justified, already adopted, already indwelt by the Spirit. The power of the age to come is breaking into this age (Heb. 6:5). So we work for justice, pursue holiness, care for creation, love our neighbors, and make disciples—not to build the kingdom by human effort, but as signs and instruments of the kingdom God is bringing.

A fourth confusion is the belief that God’s redemptive purposes can fail or be thwarted. Some fear that widespread apostasy, moral decline, or persecution means God’s plan is failing. But Scripture assures us otherwise. Jesus promised, “I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it” (Matt. 16:18). Paul declared that God “works all things according to the counsel of his will” (Eph. 1:11). Isaiah said, “My counsel shall stand, and I will accomplish all my purpose” (Isa. 46:10). God’s redemptive will is not contingent on human cooperation or cultural conditions. It is grounded in his sovereign decree and guaranteed by Christ’s finished work. The elect will be saved, the kingdom will come, and creation will be renewed—not because we make it happen, but because God has decreed it.

Finally, some struggle with the relationship between God’s redemptive will and human responsibility. If God has decreed to save his elect, why evangelize? Why pray for the lost? Why pursue mission? But again, God ordains both the ends and the means. He has decreed that people will be saved through the proclamation of the gospel (Rom. 10:14–17). He has ordained prayer as the instrument by which his purposes are accomplished (James 5:16). He commands us to make disciples (Matt. 28:19–20) and promises his presence in the task. God’s sovereignty does not cancel mission; it empowers it. We labor knowing that our work is not in vain, that God will save those he has chosen, and that the gospel is “the power of God for salvation” (Rom. 1:16).

Provide Practical Wisdom

Understanding God’s redemptive will shapes how we pray. We pray, “Your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven” (Matt. 6:10), asking God to advance his redemptive purposes in our lives, our communities, and the world. We pray for the lost, knowing God uses prayer as a means to bring people to faith (1 Tim. 2:1–4). We pray for justice, healing, reconciliation, and renewal—not as wishful thinking, but as appeals to the God who is making all things new. And we pray with confidence, knowing that God’s redemptive purposes will prevail.

God’s redemptive will also motivates mission. If we believe God is reconciling all things to himself through Christ, we join him in that work. We proclaim the gospel because it is “the power of God for salvation to everyone who believes” (Rom. 1:16). We make disciples because Christ commands it and promises to build his church (Matt. 28:19–20; 16:18). We pursue justice and mercy because these reflect God’s character and align with his redemptive purposes (Mic. 6:8; Amos 5:24). We care for creation because it, too, will be redeemed (Rom. 8:21). Mission is not optional activism; it is participation in God’s cosmic redemption project.

God’s redemptive will shapes how we suffer. Romans 8:18 says, “I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the glory that is to be revealed to us.” Suffering is real, painful, and often bewildering. But it is not ultimate. God’s redemptive purposes ensure that one day, all tears will be wiped away (Rev. 21:4), all groaning will cease (Rom. 8:23), and all that sin has broken will be healed. We endure suffering now with hope, knowing that “our light and momentary troubles are achieving for us an eternal glory that far outweighs them all” (2 Cor. 4:17, NIV). Redemption reframes suffering as temporary, purposeful, and outweighed by coming glory.

God’s redemptive will also shapes how we live ethically. If God is restoring all things, we live as agents of that restoration. Colossians 3:9–10 says, “You have put off the old self with its practices and have put on the new self, which is being renewed in knowledge after the image of its creator.” Redemption is not just a past event (justification) but an ongoing process (sanctification). We grow in holiness, putting off sin and putting on righteousness (Eph. 4:22–24). We live as “a people for his own possession, zealous for good works” (Titus 2:14). Our conduct is not the means of redemption but the fruit of it.

Understanding God’s redemptive will gives us eschatological hope. We do not hope vaguely for “something better” or pine for a disembodied heaven. We hope for what God has promised: resurrected bodies (1 Cor. 15:42–44), a new heaven and new earth (2 Pet. 3:13), the return of Christ (Acts 1:11), the defeat of death (1 Cor. 15:26), the restoration of all things (Acts 3:21). This hope is not escapism; it is the confident expectation that what God has begun, he will complete (Phil. 1:6). And this hope sustains perseverance. “Therefore, my beloved brothers, be steadfast, immovable, always abounding in the work of the Lord, knowing that in the Lord your labor is not in vain” (1 Cor. 15:58). Because God’s redemptive purposes are certain, our efforts in his service are never wasted.

Finally, God’s redemptive will calls us to worship. When we glimpse the scope of what God is doing—restoring all things, reconciling heaven and earth, defeating sin and death, bringing us into eternal joy in his presence—the only fitting response is praise. Revelation captures this: “Worthy are you, our Lord and God, to receive glory and honor and power, for you created all things, and by your will they existed and were created” (Rev. 4:11). “Worthy is the Lamb who was slain, to receive power and wealth and wisdom and might and honor and glory and blessing!” (Rev. 5:12). Redemption is God’s greatest work, and it displays his greatest glory. Our lives should be one long doxology—praise for the God who redeems.

Returning to the Mystery Revealed

When Paul wrote of “a plan for the fullness of time, to unite all things in him, things in heaven and things on earth” (Eph. 1:10), he was pulling back the curtain on the greatest story ever told. For millennia, God’s redemptive purposes were hinted at in promises and prophecies, enacted in deliverances and covenants, but never fully disclosed. Then, in Christ, the mystery was revealed. The plan is not random. History is not meaningless. God is weaving every thread—creation, fall, promise, law, exile, restoration, incarnation, crucifixion, resurrection, church, mission, consummation—into a single tapestry that displays his glory and brings his people into eternal joy.

This is not wishful optimism; it is divine decree. God’s redemptive will is not a hope that might fail but a purpose that will prevail. The Lamb who was slain is worthy to open the scroll of history (Rev. 5:9). The kingdom of this world will become the kingdom of our Lord and of his Christ (Rev. 11:15). Death will be swallowed up in victory (1 Cor. 15:54). And the cry will go up from the throne: “Behold, I am making all things new” (Rev. 21:5).

This is the will of God—the redemptive, teleological will that drives all history toward its appointed end. And what is that end? Not merely the rescue of sinners, though that is glorious. Not merely the defeat of evil, though that is necessary. Not merely the restoration of creation, though that is wondrous. The ultimate end is the display of God’s glory in the salvation of his people, the reconciliation of all things under Christ, and the eternal joy of redeemed humanity in the presence of the triune God. This is what God wills. This is what God is doing. And this is the future for which we hope, the mission in which we labor, and the God we worship. Come, Lord Jesus. Your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.

Editor’s Note

If you’ve ever felt that your life is insignificant, that history is spiraling out of control, or that evil is winning, this doctrine offers a different perspective. God is working a plan vast enough to encompass all of history yet personal enough to include you. You are not a cosmic accident. If you are in Christ, you are part of the greatest story ever told—the story of redemption. Your prayers, your obedience, your witness, your suffering, your perseverance—all of it matters because all of it fits within God’s redemptive purposes.

This does not mean life is easy or suffering is light. It does not mean you will always see how your pain serves God’s plan. But it does mean that nothing is wasted, nothing is meaningless, and the end is certain. God is making all things new, and one day you will stand in the new creation, in a resurrected body, in the presence of God, and you will see that every thread of your life—even the darkest ones—was woven into a tapestry more glorious than you could have imagined.

So live with hope. Work with purpose. Pray with confidence. Witness with boldness. Suffer with endurance. Because the God who raised Jesus from the dead is bringing his redemptive purposes to completion, and nothing—not death, not demons, not your failures, not this broken world—can stop him. The kingdom is coming. The King is returning. And all things will be united in him.