Has God withdrawn?

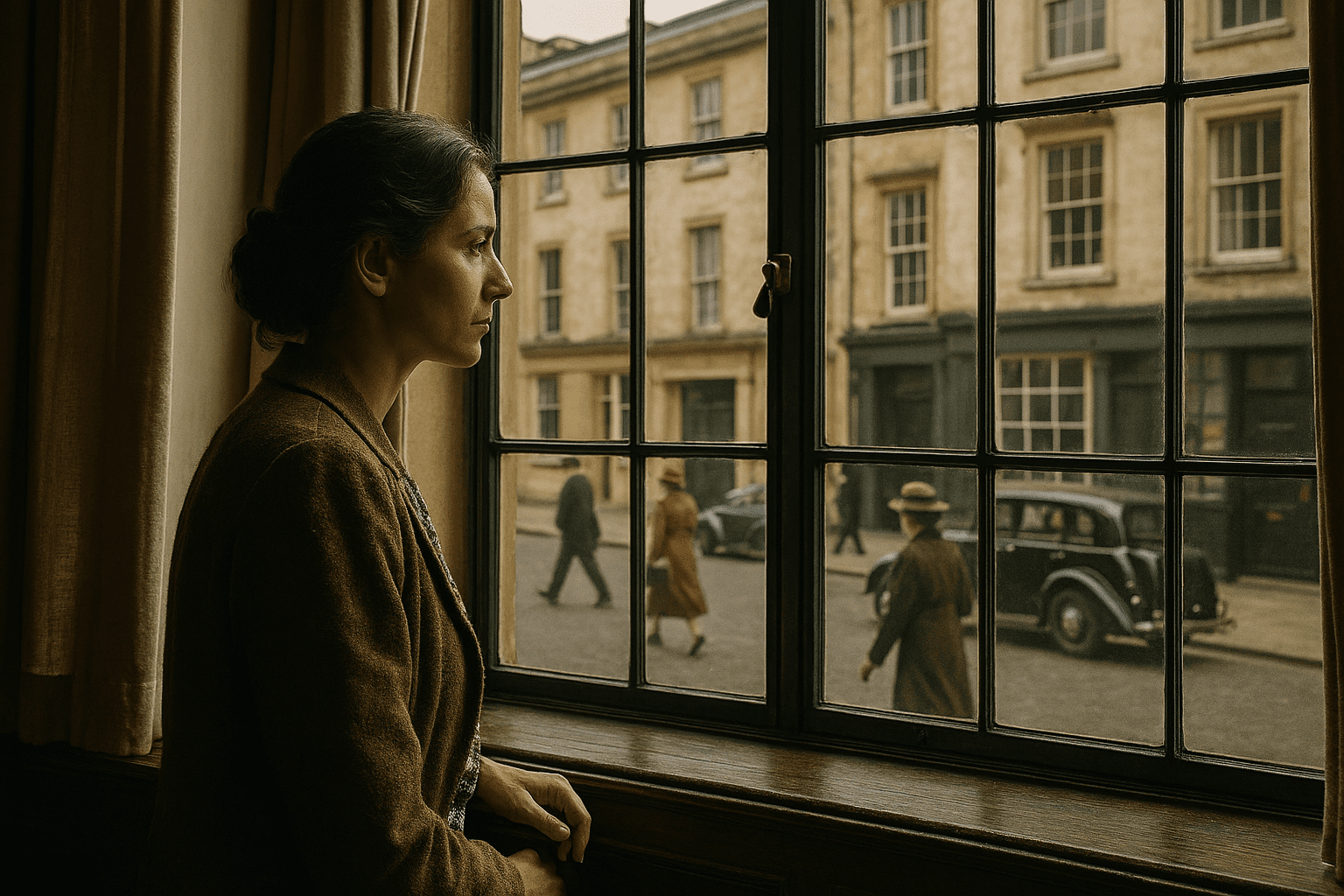

Every believer faces seasons when prayer feels like speaking into a void, when Scripture seems flat, when the warm assurance of God’s presence gives way to cold silence.

Do Feelings Match Reality?

“The LORD is near to the brokenhearted and saves the crushed in spirit”

—Psalm 34:18, ESV

Draw near to God, and he will draw near to you”

— James 4:8, ESV

These two statements stand as a compressed summary of Scripture’s insistence: God’s presence is a revealed and promised reality, and yet human beings are summoned to respond. The Bible never leaves the felt life of the soul unaddressed. It names both the objective fact of divine nearness in covenant and incarnate presence, and the practical, pastoral realities that explain why a person—saint or seeker—may not sense that nearness. The question we face is not whether God is near but why our perception of that nearness sometimes fails, and what the Scriptures bid us to do in such seasons.

Every believer faces seasons when prayer feels like speaking into a void, when Scripture seems flat, when the warm assurance of God’s presence gives way to cold silence. The question then becomes urgent and personal: Has God withdrawn, or has something in us shifted? The answer Scripture gives is both consoling and convicting—God’s nearness is a covenant reality that does not depend on our perception, yet our souls require tending. The path forward involves both theological clarity about what is objectively true and pastoral wisdom about why our experience sometimes lags behind that truth.

God’s Nearness in Scripture

From the Psalms to the Pauline letters, Scripture insists that God is intimately present with his people. The Psalms repeatedly give voice to a God who is “near to the brokenhearted” (Psalm 34:18 ESV) and “near to all who call on him, to all who call on him in truth” (Psalm 145:18 ESV). Isaiah’s oracle comforts trembling hearts with the simple promise, “Fear not, for I am with you” (Isaiah 41:10 ESV). The incarnate Lord declares his abiding presence to his disciples: “And behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age” (Matthew 28:20 ESV). The writer to the Hebrews anchors Christian courage in the same covenantal assurance: “For he has said, ‘I will never leave you nor forsake you’” (Hebrews 13:5 ESV).

The New Testament further clarifies the mode of that nearness: God comes to dwell within believers by his Spirit. Paul’s sober assertion—”If anyone does not have the Spirit of Christ, he does not belong to him” (Romans 8:9 ESV)—makes the point stark: nearness is not merely God being “nearby” in a general sense; it is God’s indwelling presence in those united to Christ. Thus the biblical picture is double: God is objectively near because of his covenant promises and uniquely near to those who are in Christ by the Spirit.

But Scripture does not treat nearness as a static metaphysical proposition only. The biblical authors also call God’s people to active response: to draw near, to seek, to call. James’s succinct injunction—”Draw near to God, and he will draw near to you” (James 4:8 ESV)—ties divine initiative to human turning. Hebrews entreats the community to “draw near with a true heart in full assurance of faith” (Hebrews 10:22 ESV). Isaiah exhorts the people to “seek the LORD while he may be found; call upon him while he is near” (Isaiah 55:6 ESV). These imperative texts presuppose the reality of God’s presence but insist that humans must reorient toward it.

It is important to keep the theological distinction clear. The Bible teaches an objective reality—God’s nearness in covenant, incarnate presence, and Spirit-indwelling—that is true whether or not our senses register it. At the same time, Scripture speaks plainly about subjective experience: human perception of God varies, is fallible, and can be clouded. The Reformation language of objective justification versus subjective assurance is helpful here: a believer’s standing in Christ is a settled fact; the believer’s felt assurance can wax and wane. This distinction matters pastorally. When a believer says, “I can’t feel God near,” the first pastoral reply drawn from Scripture is to affirm the stability of God’s promises. But the pastoral story does not end there; the Bible also invites practical attention to the soul, diagnosing the reasons for spiritual darkness and offering means for renewed awareness.

Why Believers Sometimes Can’t Feel God’s Presence

Scripture provides multiple answers to why the regenerate can find themselves in seasons where God’s presence is not felt. These are not exhaustive, but they are the most recurrent and pastorally significant.

First, and most sobering, is the burden of unconfessed sin. The Psalms testify to the corrosive effect of hidden sin and silence before God. “When I kept silence, my bones wasted away through my groaning all day long” (Psalm 32:3–4 ESV). David’s confession—”I acknowledged my sin to you, and I did not cover my iniquity; I said, ‘I will confess my transgressions to the LORD’—and you forgave the iniquity of my sin” (Psalm 32:5 ESV)—connects restoration of fellowship with the renewal of joy and peace. John similarly links confession and cleansing: “If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just to forgive us our sins and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness” (1 John 1:9 ESV). The pastoral implication is simple: unconfessed sin narrows fellowship and dulls the conscience, which in turn dims apprehension of God’s nearness.

Beyond the question of sin, Scripture also recognizes seasons of spiritual dryness—times when the discipline of faith is tested by absence of feeling. The psalmist asks poignantly, “How long, O LORD? Will you forget me forever? How long will you hide your face from me?” (Psalm 13:1 ESV). Yet the same psalm turns to remembrance and praise; the pattern is instructive: honesty before God about absence is itself a form of prayer. Puritan writers, and later other spiritual leaders, have often pointed to dryness as an instrument of sanctification—an occasion for faith to learn reliance on God when feeling fails. Scripture urges perseverance: “Consider it pure joy… whenever you face trials of many kinds, because you know that the testing of your faith produces steadfastness” (James 1:2–3 ESV).

The body’s frailty also matters. Biblical narrative is honest about the body and soul’s complexities. Jesus wept (John 11:35 ESV); he also groaned in spirit (Mark 8:12 ESV). The apostle Paul describes seasons of such pressure that he despaired of life itself (2 Corinthians 1:8–10 ESV). Modern understandings of depression and anxiety reveal physiological and neurological dimensions to spiritual experience, yet Scripture models both compassion and practical care. Where mental illness or overwhelming grief impairs spiritual sense, the Bible calls for mutual ministry: pastoral presence, practical aid, and, when appropriate, medical help.

Neglect of the ordinary means of grace often explains felt distance from God. God ordinarily speaks through means: Scripture, prayer, the sacraments, preaching, and the local community. Psalm 119 petitions, “Open my eyes, that I may behold wondrous things out of your law” (Psalm 119:18 ESV), assuming that Scripture is the instrument of reorientation. Likewise, the New Testament’s insistence on corporate worship and mutual exhortation—”not neglecting to meet together, as is the habit of some, but encouraging one another” (Hebrews 10:25 ESV)—recognizes the communal shape of spiritual life. Withdrawal from these means will typically narrow the channels of God’s communication.

There is also a cultural temptation to equate faith with constant emotional uplift or unbroken spiritual consolation. The New Testament corrects this expectation with the steady assertion that faith is trust in God’s acts, not the fluctuation of feeling. “We walk by faith, not by sight” (2 Corinthians 5:7 ESV) names the Christian’s calling to trust where perceiving fails. Expectation recalibrated toward God’s promises rather than immediate sensation transforms endurance into worship.

Finally, the process of sanctification itself can produce seasons of disquiet. Paul speaks of the groaning of creation and of believers who await adoption as sons (Romans 8:23 ESV). As God strips idols and reveals hidden dependencies, the soul can feel impoverished before it is renewed. This is not evidence of divine absence but evidence of divine surgery—painful yet purposing restoration.

Pathways Back to Felt Nearness

Scripture’s diagnoses are matched by scriptural remedies—practical, sacramental, communal, and pastoral. These are not mechanical prescriptions but faithful pathways that the Bible commends.

The first is the discipline of memory. The psalmist’s practice of remembrance becomes normative. “I will remember the deeds of the LORD; yes, I will remember your wonders of old” (Psalm 77:11 ESV). Remembering the factual promises—Hebrews’ “I will never leave you nor forsake you” (Hebrews 13:5 ESV), Jesus’ “I am with you always” (Matthew 28:20 ESV)—is a spiritual discipline. Memory exercises the mind and anchors the heart to covenant truth when feelings drift.

Closely related is the call to confession and repentance. James’s appeal—”Draw near to God, and he will draw near to you” (James 4:8 ESV)—is integrally bound to repentance. A humbled heart that names its sins opens to receive grace. 1 John 1:9’s promise is both theological and pastoral: public or private confession restores the believer to the open fellowship that makes nearness felt.

The ordinary instruments of grace must be reengaged. Scripture reading, prayer, sacramental participation where appropriate, and faithful communal worship are the primary avenues by which God ordinarily makes his presence known. Scripture invites the weary to “come to me, all who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest” (Matthew 11:28 ESV), and it equips the church to be a means of grace through preaching, sacraments, and care.

When absence is complicated by depression, trauma, or persistent spiritual distress, Scripture’s pastoral care includes professional aid. Paul’s own appeals, and the New Testament’s practical wisdom, allow for a church that attends to body and mind. Shepherds should shepherd, but they should also direct those in deep distress toward the necessary medical resources.

Finally, Scripture commends the practice of patient endurance and lament. The biblical way through darkness often passes by lament. The Psalms are full of lamentation that does not despair: “Out of the depths I cry to you, O LORD!” (Psalm 130:1 ESV). Lament gives voice to sorrow while holding to the hope of rescue. In this way faith is not the suppression of feeling but its honest offering to God.

A Word to the One Who Is Not Yet Regenerate

For the reader who finds these pages because of a newfound stirring—an unusual openness, an ache in the soul, a hunger for meaning—the Bible offers both a diagnosis and an invitation. The diagnosis is frank: humanity is estranged from God by sin. “All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23 ESV). The heart is described as “deceitful above all things, and desperately sick” (Jeremiah 17:9 ESV). This diagnosis is not meant to shame but to remove false confidence and show the seriousness of the problem.

But Scripture’s good news is immediate and specific. The movement from death to life is the Lord’s making. “But God, being rich in mercy, because of the great love with which he loved us, even when we were dead in our trespasses, made us alive together with Christ—by grace you have been saved” (Ephesians 2:4–5 ESV). Jesus himself promises, “Whoever comes to me I will never cast out” (John 6:37 ESV), and Paul assures that “everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved” (Romans 10:13 ESV).

What does the Scripture call for? Repentance and faith. Repentance is a turning—a reorientation of the will away from self and sin and toward Christ. Faith is a trusting reliance on Jesus and his finished work. These are not accomplishments we muster by moral strength; they are gifts wrought by God’s Spirit. John declares the necessity of new birth: “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless one is born again he cannot see the kingdom of God” (John 3:3 ESV). Yet Jesus also assures that the Father draws sinners: “No one can come to me unless the Father who sent me draws him” (John 6:44 ESV).

Practical next steps for an awakening soul are simple and clear in Scripture: acknowledge your need in prayer, ask God to make Christ real to you, begin reading the Gospel of John to behold Jesus, and seek out a church where the Word is proclaimed and the sacraments are rightly administered. The invitation is urgent but merciful: “Seek the LORD while he may be found; call upon him while he is near” (Isaiah 55:6 ESV).

Conclusion and Pastoral Encouragement

Scripture holds the tension without contradiction: God is near in covenant and incarnate presence, and yet human beings are summoned to draw near. For the believer who cannot feel God’s presence, Scripture offers firm consolation: the Spirit dwells in God’s elect whether or not sensation coincides. For the one awakening to the reality of spiritual need, Scripture offers a clear and immediate remedy: come to Christ, repent, and believe.

The pastoral voice the Bible gives us is tender, truthful, and urgent. It acknowledges honest lament, provides concrete means for restoration, and never reduces faith to mere feeling. The Lord’s promises—”The LORD is near to the brokenhearted” (Psalm 34:18 ESV); “I will never leave you nor forsake you” (Hebrews 13:5 ESV); “And behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age” (Matthew 28:20 ESV)—are the bedrock under every human season of doubt or awakening. Whether you are a disciple who grows restless in the night or a stranger at the edge of the fold whose heart is beginning to stir, the same merciful summons comes from Scripture: draw near to God, and he will draw near to you (James 4:8 ESV). The truth is not finally about how we feel in a given hour but about the faithful God who draws close and calls us home.

“The LORD is near to the brokenhearted and saves the crushed in spirit” (Psalm 34:18 ESV); “Draw near to God, and he will draw near to you” (James 4:8 ESV). These twin truths frame the Christian life: a God who is present by covenant and a people who are invited to return, seek, and abide. Wherever you stand—assured in Christ, or newly aware of need—the Bible’s word is the same: the Shepherd is near, and he calls you to draw near to him.

Editor’s Note: To the Spirit-filled believer, nearness to God is not a feeling—it is a position. As the article above explains, there are many reasons a believer may feel distant from God, and of those, neglect is particularly common. Neglect of what? Neglecting such a great salvation. We explored this further in “So Great a Salvation,” examining how we forget to treasure God and the salvation granted to us, instead treasuring the things of the world.

If you suspect God is using spiritual dryness as an instrument of sanctification, ask your brothers and sisters in Christ for prayer as He transforms you. Perhaps that lack of “nearness feeling” is meant to draw you to treasure Him more, to treasure your position in Christ more deeply, and ultimately to draw you nearer to Him.

For those who wonder how unregenerate people may understand this article’s biblical truths, remember this is part of the mystery of salvation. People who are spiritually dead cannot initiate a response to God—it is God who first opens the heart, mind, eyes, and ears. To those starting to hear the shepherd’s voice as a faint calling: draw near to Him who is calling you. For more on this topic: Unblinded to Choose?