Spiritual Resurrection ?

Eschatologically, it anticipated the resurrection of the dead and the establishment of God’s eternal kingdom.

An Exegetical Analysis of Lauren Daigle’s “Dry Bones”

The Divine Breath of Restoration

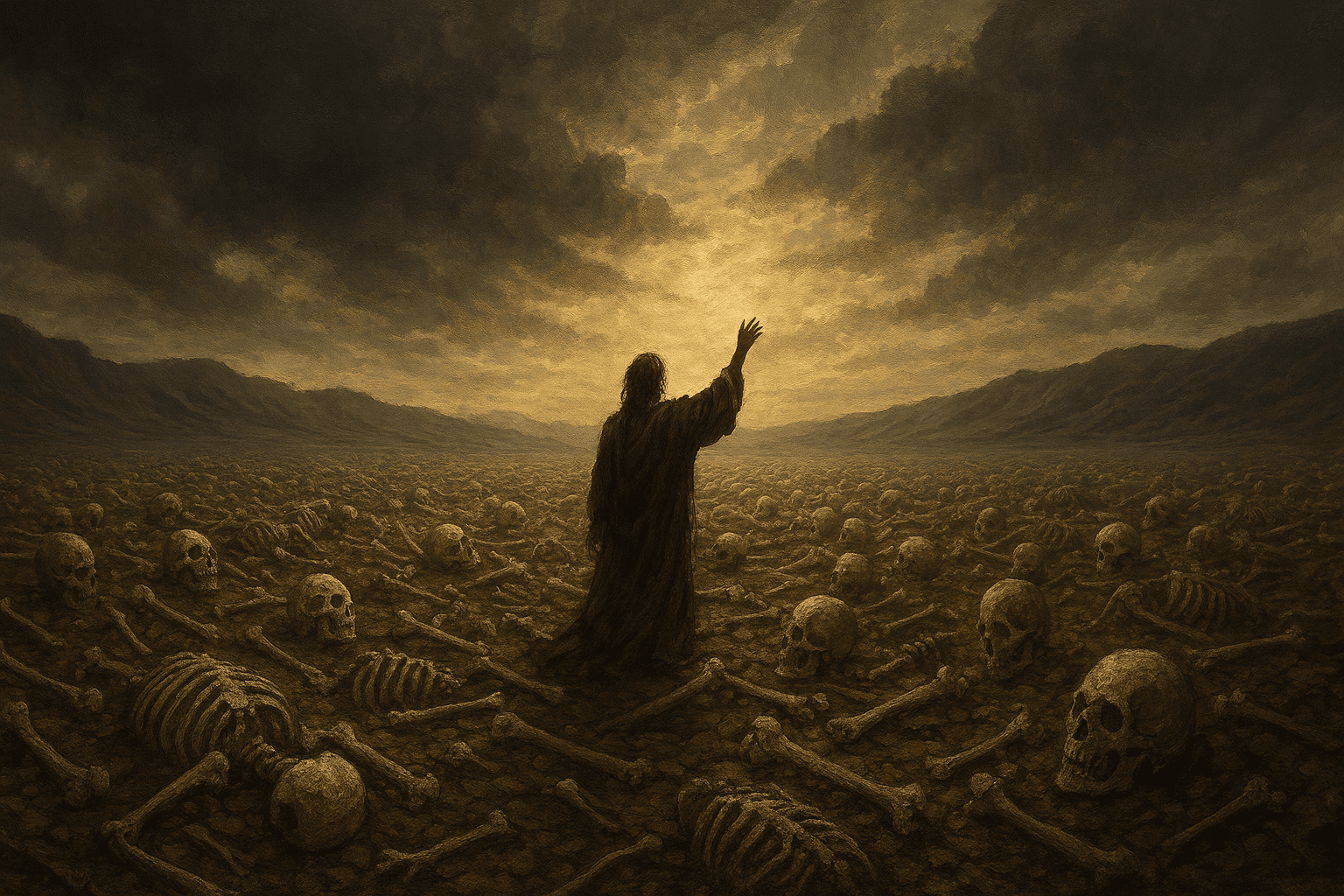

“The hand of the Lord was upon me, and he brought me out in the Spirit of the Lord and set me down in the middle of the valley; it was full of bones… And he said to me, ‘Son of man, can these bones live?’ And I answered, ‘O Lord God, you know.’ Then he said to me, ‘Prophesy over these bones, and say to them, O dry bones, hear the word of the Lord.’” — Ezekiel 37:1, 3-4 (ESV)

Ezekiel’s prophetic vision of resurrection in the valley of dry bones stands as one of Scripture’s most vivid portraits of divine power to restore what appears irredeemably lost. The image of scattered bones receiving sinew, flesh, and breath through prophetic proclamation has captivated believers across millennia as both historical promise to exiled Israel and eternal hope for spiritual resurrection. Yet when contemporary worship songs appropriate such powerful biblical imagery, they risk either trivializing the original context or creating false expectations about divine intervention. Does Lauren Daigle’s “Dry Bones” honor the typological richness of Ezekiel’s vision while maintaining theological accuracy, or does it venture into territory that sounds biblical but lacks exegetical foundation?

The Contemporary Prophet’s Voice

“Dry Bones,” written by Lauren Daigle, Michael Farren, and Michael Weaver, was released in 2018 on Daigle’s album “Look Up Child.” The Contemporary Christian Music composition draws explicitly from Ezekiel’s prophetic vision while addressing contemporary concerns about spiritual deadness and the church’s role in proclaiming restoration. This biographical and textual context raises the central theological question: Does Daigle’s appropriation of Ezekiel’s imagery accurately reflect the biblical text’s meaning and application, maintaining proper hermeneutical boundaries between Old Testament historical promise and contemporary spiritual reality?

The song’s framework presents believers as prophetic voices calling for spiritual resurrection in apparently hopeless circumstances—prodigal children, spiritually dead hearts, lives reduced to ashes. This application of prophetic ministry to the contemporary church demands careful examination against Scripture’s teaching on prophetic authority, spiritual resurrection, and the means by which God accomplishes restoration.

Biblical Foundations and Lyrical Fidelity

The Original Vision: Context and Meaning

Ezekiel 37:1-14 provides the foundational text that Daigle’s song explicitly references. The prophet’s vision occurred during Israel’s Babylonian exile, when the nation’s political, religious, and social structures lay in ruins. The scattered bones represented Israel’s despair: “Our bones are dried up, and our hope is lost; we are indeed cut off” (Ezekiel 37:11). God’s command to prophesy restoration addressed both immediate historical circumstances and ultimate eschatological hope.

Crucial to proper interpretation is understanding the vision’s dual fulfillment. Historically, it promised Israel’s return from exile and national restoration. Eschatologically, it anticipated the resurrection of the dead and the establishment of God’s eternal kingdom. The New Testament applies Ezekiel’s imagery to spiritual regeneration (John 3:8, where Jesus references the Spirit’s work like wind) and final resurrection (1 Corinthians 15:35-49).

Daigle’s opening observation that through human eyes there appears to be much loss, followed by reference to prodigals who have walked away, establishes the contemporary application. This parallel between Israel’s exile and individual spiritual wandering contains legitimate typological connections—both involve covenant people separated from their intended relationship with God through disobedience and spiritual deadness.

The Nature of Prophetic Proclamation

The song’s central action involves calling out to dry bones and dead hearts to “come alive.” This appropriation of Ezekiel’s prophetic role requires careful theological examination. In the original vision, Ezekiel spoke not on his own authority but as direct recipient of divine command: “Prophesy over these bones, and say to them, O dry bones, hear the word of the Lord” (Ezekiel 37:4).

The question arises: Do contemporary believers possess similar prophetic authority to command spiritual resurrection? Scripture teaches that all believers participate in gospel proclamation (Matthew 28:19-20, 2 Corinthians 5:20), yet it maintains clear distinctions between apostolic/prophetic authority and general Christian witness. The New Testament pattern shows spiritual life coming through gospel preaching (Romans 10:17, 1 Peter 1:23) rather than through direct command to the spiritually dead.

However, Daigle’s framework can be understood as representing prayer and gospel proclamation rather than claiming prophetic authority. The repeated phrase “we call out” suggests petitioning God for resurrection rather than commanding it directly. This interpretation aligns with biblical patterns of intercession for the spiritually lost (Romans 10:1, 1 Timothy 2:1-4) and evangelical witness that proclaims life to the dead (Ephesians 2:1-5).

The Agency of Spiritual Resurrection

Theologically crucial is the song’s treatment of who accomplishes spiritual resurrection. The lyrics maintain proper emphasis on divine agency: “But we know that you are God / Yours is the victory” and “Show the world that you alone can save / You alone can save.” This emphasis aligns perfectly with Scripture’s teaching that spiritual life originates solely from God’s power.

Ephesians 2:1-5 establishes the pattern: “And you were dead in the trespasses and sins… But God, being rich in mercy, because of his great love with which he loved us, even when we were dead in our trespasses, made us alive together with Christ.” The passive construction emphasizes divine initiative rather than human contribution to the resurrection process.

The song’s bridge, invoking “breath of God” repeatedly, directly parallels Ezekiel 37:9-10, where God commands the breath to enter the assembled bodies: “Come from the four winds, O breath, and breathe on these slain, that they may live.” In Hebrew, the word ruach means both breath, wind, and spirit, connecting physical breath with spiritual life. John 3:8 employs similar imagery when Jesus explains to Nicodemus that spiritual birth comes from the Spirit’s sovereign work.

Typological Integrity and Contemporary Application

The song’s application of Ezekiel’s vision to contemporary spiritual deadness raises questions of typological integrity. Proper biblical typology maintains correspondence between the historical situation and contemporary application while respecting the unique features of both contexts.

The correspondence appears legitimate: both ancient Israel and contemporary prodigals experience separation from God, spiritual deadness, and need for divine intervention. The pattern of divine restoration through prophetic proclamation finds New Testament fulfillment in gospel preaching that brings spiritual life to the dead (Romans 1:16, 1 Corinthians 1:18).

However, important distinctions must be maintained. Ezekiel’s vision addressed national restoration with specific historical promises about land, temple, and political structure. Contemporary application must focus on the spiritual reality that the historical events typified rather than claiming identical promises for modern situations.

The song navigates this appropriately by focusing on spiritual rather than material restoration—dead hearts coming alive, spiritual armies rising, wayward sons returning. This maintains the typological connection while respecting the unique historical context of Ezekiel’s prophecy.

The Problem of Spiritual Deadness

Daigle’s diagnosis of spiritual deadness requires biblical examination. The opening verses attribute this condition to enemy deception: “One by one / The enemy has whispered lies / And led them off as slaves.” This explanation aligns with Scripture’s teaching on Satan’s role in spiritual blindness (2 Corinthians 4:4, Ephesians 2:2) and deception (John 8:44, Revelation 12:9).

However, Scripture also emphasizes human responsibility in spiritual deadness. Romans 1:18-32 describes the process by which people “suppress the truth in unrighteousness” and experience progressive hardening. Ephesians 4:17-19 attributes spiritual darkness to “futility of their minds” and hardness of heart. A complete biblical diagnosis includes both Satanic deception and human culpability.

The song’s emphasis on enemy activity, while biblically accurate, could minimize the human responsibility aspect that Scripture consistently maintains. This theological balance proves crucial for proper understanding of both the problem (sin’s guilt and power) and the solution (divine grace addressing both aspects).

The Scope of Divine Mercy

The song’s portrayal of God as “God of endless mercy / God of unrelenting love” who will “rescue every daughter / Bring us back the wayward son” raises questions about the extent of divine salvation. The universal language (“every daughter,” “the wayward son”) could suggest either universal salvation or confident expectation of comprehensive restoration within the covenant community.

Biblical teaching maintains tension between God’s universal love (John 3:16, 1 Timothy 2:4) and the reality that not all will be saved (Matthew 7:13-14, 2 Thessalonians 1:8-9). God’s mercy is indeed endless for those who repent and believe, yet Scripture consistently warns of the possibility of final hardening and judgment.

The song’s language functions better as expression of hope and prayer rather than prophetic declaration of universal restoration. This interpretation aligns with biblical patterns of intercession that express confident hope in God’s mercy while acknowledging the necessity of individual response to grace.

Discerning the Writer’s Spiritual Posture

The lyrical content reveals a spiritual posture characterized by faith despite appearances, confident intercession, and evangelical concern for the lost. The acknowledgment that through human perspective “there’s so much we have lost” combined with faith that “there is more to come” demonstrates the tension between sight and faith that marks mature Christian experience (2 Corinthians 5:7, Hebrews 11:1).

The repeated emphasis on God’s exclusive saving power (“you alone can save”) reflects appropriate theological humility that recognizes human limitations while maintaining confident expectation in divine capability. This posture aligns with biblical intercession patterns that combine realistic assessment of human need with bold appeal to divine power.

The song’s triumphant tone, calling for armies to rise from ashes, suggests a heart that has experienced or witnessed divine restoration and expects similar intervention in present circumstances. This optimism, grounded in God’s character rather than circumstances, reflects the “heart of flesh” that Scripture describes as responsive to divine purposes (Ezekiel 36:26).

However, the lyrics lack the element of lament or detailed confession that often accompanies biblical calls for restoration. The Psalms frequently combine confident appeal with honest acknowledgment of sin and failure (Psalm 51, 80, 126). While not theologically incorrect, this omission means the song addresses only part of the restoration pattern that Scripture typically includes.

Categorical Suitability Assessment

Corporate Worship Evaluation

As a Contemporary Christian Music composition explicitly written for Christian audiences, “Dry Bones” requires full evaluation for corporate worship suitability. The song demonstrates several strengths that support congregational use while requiring attention to specific theological concerns.

Biblical Foundation: The explicit connection to Ezekiel’s vision provides solid scriptural grounding that congregations can recognize and appreciate. The imagery resonates with believers familiar with the biblical narrative while remaining accessible to those less versed in Old Testament prophecy.

Theological Orthodoxy: The song maintains essential Christian doctrines—divine sovereignty in salvation, human need for spiritual resurrection, Christ’s exclusive saving power, and the Spirit’s role in regeneration. These themes align with core evangelical beliefs suitable for congregational confession.

Evangelical Focus: The emphasis on calling for spiritual awakening and restoration serves the church’s missionary purpose, encouraging congregational engagement in evangelism and intercession for the lost. This outward focus prevents the song from becoming merely experiential or self-focused.

Pastoral Concerns: The song’s confident expectation of restoration could create unrealistic expectations about timing or certainty of specific outcomes. Congregations might misunderstand the difference between confident prayer and prophetic guarantee, potentially leading to disappointment when expected resurrections don’t occur according to human timelines.

Musical and Literary Quality: The song demonstrates strong musical composition with effective use of biblical imagery and contemporary language. The repetitive structure serves both congregational singing and meditative reflection.

Verdict: Suitable for corporate worship with pastoral framing to clarify the distinction between confident intercession and prophetic declaration, and to maintain realistic expectations about divine timing in restoration.

Personal Devotion Assessment

For individual believers, “Dry Bones” offers significant devotional value, particularly for those burdened by concern for spiritually lost family members or friends. The song provides biblical language for intercession while encouraging faith despite discouraging appearances.

The connection to Ezekiel’s vision invites deeper biblical study and meditation on God’s power to restore what appears hopelessly lost. This can strengthen personal faith and provide comfort during seasons when prayer seems ineffective or circumstances appear insurmountable.

The repeated invocation of God’s breath connects personal prayer with the broader biblical theme of divine life-giving power, from Genesis creation (Genesis 2:7) through Pentecost (Acts 2:2-4) to final resurrection (1 Corinthians 15:45). This theological richness supports extended personal reflection.

However, individual use requires biblical balance to avoid the presumption that human calling automatically produces divine response or that spiritual resurrection occurs according to human timelines. The song works best when balanced with Scripture’s teaching on divine sovereignty, human responsibility, and the mystery of conversion timing.

Verdict: Highly suitable for personal devotion, particularly beneficial for intercession and as encouragement during seasons of concern for spiritually lost loved ones.

Doctrinal and Pastoral Considerations

Several areas require careful pastoral attention to prevent theological misunderstanding:

- Prophetic Authority: The song’s use of command language (“come alive”) could be misunderstood as claiming prophetic authority rather than expressing confident prayer. Clear teaching about the distinction prevents inappropriate expectations about believer’s spiritual authority.

- Conversion Certainty: The confident tone might suggest that proper prayer guarantees specific outcomes rather than expressing faith in God’s power and willingness to save. Pastoral guidance should emphasize divine sovereignty in salvation timing and methods.

- Human Agency: While maintaining proper emphasis on divine power, the song could benefit from clearer acknowledgment of human responsibility in responding to gospel proclamation.

- Eschatological Tension: The song’s triumphant expectation of restoration needs balance with biblical teaching about the “already/not yet” nature of kingdom victory, preventing unrealistic expectations about complete earthly restoration.

These concerns don’t disqualify the song but indicate areas where broader biblical teaching provides necessary theological context.

The Valley of Divine Possibility

Returning to Ezekiel’s extraordinary vision in the valley of dry bones, we discover both the power and the proper boundaries of Lauren Daigle’s contemporary adaptation. Like the ancient prophet’s proclamation, the song calls forth life in apparently hopeless circumstances, maintaining confidence in divine power to accomplish what human effort cannot achieve.

The song succeeds in capturing the essential biblical truth that God specializes in resurrection—bringing life from death, hope from despair, restoration from ruin. Daigle’s lyrical theology maintains proper emphasis on divine agency while encouraging believers to participate through prayer and proclamation in God’s restorative work. The explicit biblical foundation provides congregations with solid theological grounding for their intercession and evangelical efforts.

Most significantly, “Dry Bones” demonstrates how contemporary worship can appropriately adapt biblical imagery to address current spiritual needs without abandoning scriptural accuracy. The song’s treatment of spiritual deadness, divine mercy, and restoration power aligns with both Ezekiel’s original vision and New Testament teaching on spiritual regeneration.

However, the song’s confident expectation of restoration requires pastoral wisdom to prevent misunderstanding about divine timing, human authority, and the certainty of specific outcomes. While God indeed possesses power to resurrect any spiritual deadness, His methods and timing often exceed human understanding and expectation.

For the contemporary church seeking to maintain both biblical fidelity and evangelical fervor, “Dry Bones” offers a valuable resource that encourages bold intercession while pointing toward the God who alone can save. It serves not as guarantee of specific outcomes but as invitation to participate in the ancient prophetic pattern of proclaiming life to death, hope to despair, and divine possibility to human impossibility.

The song’s enduring impact reflects the church’s deep need for hope regarding spiritually lost loved ones and confidence in God’s restorative power. As believers continue to witness spiritual deadness in family members, communities, and culture, “Dry Bones” provides biblical language for their intercession and encouragement for their faith. In this role, it points ultimately toward the God whose breath first gave life to Adam, whose Spirit gives spiritual birth to believers, and whose power will ultimately raise the dead in final resurrection—the same God who can breathe life into the driest bones and most hopeless situations according to His perfect will and timing.