Two mentions, one prayer modeled.

Together, they teach us what to ask for, in what order, and with what heart. This is formation through the Master’s instruction—learning to pray from the One who prayed perfectly.

Prayer – Matthew 6:9-13 & Luke 11:2-4

…the master template for kingdom priorities.

This article is part of our Prayers Series—a focused exploration of how Scripture teaches us to pray through biblical examples.

The Lord’s Prayer and the Architecture of Kingdom Communion

“Pray then like this: ‘Our Father in heaven, hallowed be your name. Your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread, and forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors. And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil.’”

— Matthew 6:9-13, ESV

“When you pray, say: ‘Father, hallowed be your name. Your kingdom come. Give us each day our daily bread, and forgive us our sins, for we ourselves forgive everyone who is indebted to us. And lead us not into temptation.’”

— Luke 11:2-4, ESV

Two Gospel writers, two contexts, one prayer.

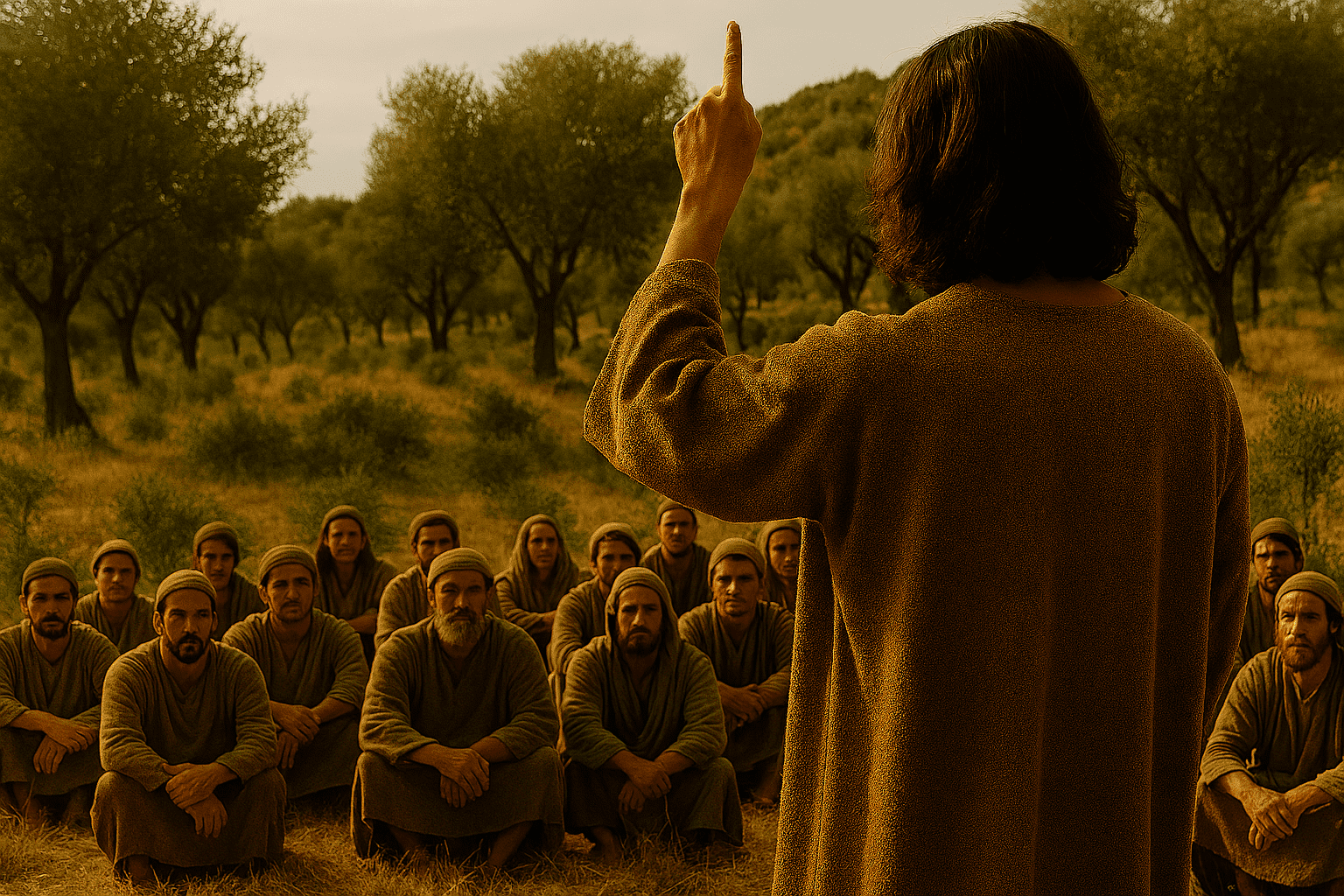

Matthew records Jesus teaching within the Sermon on the Mount—comprehensive kingdom instruction for gathered crowds. Luke captures the intimate moment when disciples, having watched Jesus pray, ask directly: “Lord, teach us to pray.” Same prayer, different settings. Same heart, different emphases.

This is not just the Lord’s Prayer. It’s the pattern for all prayer—given twice to ensure we don’t miss its significance.

Why This Prayer Matters

The Lord’s Prayer stands as Christianity’s master template for communion with God. Where Paul’s prayers show us intercession and Daniel’s prayer models confession, Jesus’ prayer establishes the fundamental priorities and posture of all biblical prayer. Having two Gospel accounts allows us to see both the comprehensive framework (Matthew) and the essential elements (Luke).

Matthew’s version provides the complete architectural blueprint—six petitions that move from God’s glory to human need, from eternal concerns to temporal necessities. Luke’s version offers the stripped-down essentials—five core elements for disciples learning to pray.

Together, they teach us what to ask for, in what order, and with what heart. This is formation through the Master’s instruction—learning to pray from the One who prayed perfectly.

Walking Through the Prayer

1. Our Father in Heaven / Father

Matthew: “Our Father in heaven…” Luke: “Father…”

Both Gospels begin with relationship, not ritual. Matthew’s “Our Father in heaven” balances intimacy with transcendence—family closeness with eternal majesty. Luke’s simple “Father” captures the Aramaic “Abba” Jesus used—the intimate address that revolutionized prayer.

The difference is emphatic, not essential. Matthew emphasizes God’s transcendence (“in heaven”) for those who might presume upon divine intimacy. Luke emphasizes accessibility (“Father”) for disciples learning that God is approachable. Both establish that prayer begins with relationship, not religion.

The word “Father” (πατήρ) establishes the tone and theology of everything that follows. If God is truly Father, then His name deserves honor, His kingdom demands priority, His will requires submission, His provision can be trusted, His forgiveness can be sought, and His protection can be claimed.

2. Hallowed Be Your Name

Both: “hallowed be your name.”

Both accounts agree perfectly here. The first petition is identical—not about us but about God. “Hallowed” (ἁγιασθήτω) is aorist passive: “let your name be sanctified” or “treated as holy.” This isn’t asking God to make His name more holy (impossible) but praying that His character would be honored, His reputation restored, His glory displayed.

In Hebrew thought, “name” represents character and reputation. To pray “hallowed be your name” is to pray that God would be rightly regarded by creation. This must come first—God’s honor before human comfort, divine reputation before personal relief.

3. Your Kingdom Come

Both: “Your kingdom come.”

Again, both accounts align perfectly. “Kingdom” (βασιλεία) refers not to territory but to sovereignty—God’s rule, authority, and dominion. This has both present and future dimensions: we pray for God’s kingdom to come now in our hearts and ultimately when Christ returns.

Notice this comes before personal requests. We pray for God’s reign before our relief, His authority before our agenda, His kingdom before our comfort.

4. Your Will Be Done (Matthew Only)

Matthew: “your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.” Luke: [omitted]

Matthew includes the third God-centered petition; Luke moves directly to human needs. This isn’t contradiction but emphasis. Matthew’s fuller version specifies what kingdom-coming looks like: God’s will being done on earth as completely as in heaven.

Luke’s omission doesn’t diminish the concept—”Your kingdom come” implies God’s will being done. But Matthew makes it explicit, perhaps for readers who need to understand that kingdom prayer requires will-submission.

The phrase “on earth as it is in heaven” provides the standard: perfect, immediate, joyful obedience to God’s desires. This echoes Jesus in Gethsemane: “Not my will, but yours be done.”

5. Give Us Daily Bread

Matthew: “Give us this day our daily bread” Luke: “Give us each day our daily bread”

Both shift from God’s glory to human need, but notice the order—only after praying for God’s name, kingdom, and will do we pray for provision. The word “bread” (ἄρτος) represents basic sustenance, not luxury.

Matthew emphasizes “this day”—present focus rather than future anxiety. Luke emphasizes “each day”—ongoing dependence rather than one-time provision. Together they teach daily trust without tomorrow’s worry.

Both assume dependence (“give us”) and community (“us,” not “me”). We don’t demand but ask, and even personal needs are prayed within corporate context.

6. Forgive Us Our Debts/Sins

Matthew: “forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors” Luke: “forgive us our sins, for we ourselves forgive everyone who is indebted to us”

Both address our deepest need: forgiveness. Matthew uses “debts” (ὀφειλήματα)—moral obligations we’ve failed to pay. Luke uses “sins” (ἁμαρτίας)—missing the mark, moral failure. Both words capture the same reality: we owe God what we cannot pay.

The connection to forgiving others appears in both but with different nuance. Matthew: “as we also have forgiven” suggests comparison—we ask for forgiveness in proportion to how we forgive. Luke: “for we ourselves forgive” suggests evidence—we demonstrate having received forgiveness by extending it.

Both teach that unforgiveness reveals an unforgiven heart. This isn’t earning God’s mercy but showing we’ve received it.

7. Lead Us Not Into Temptation

Matthew: “And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil” Luke: “And lead us not into temptation”

Both seek protection from spiritual danger. “Lead us not” (μὴ εἰσενέγκῃς) asks God not to bring us into situations where we might fall. “Temptation” (πειρασμός) can mean testing or trial—circumstances that reveal spiritual condition.

Matthew adds “but deliver us from evil” (or “the evil one”), emphasizing protection from Satan’s attacks. Luke’s shorter version focuses solely on avoiding temptation rather than escape from it.

Both acknowledge ongoing vulnerability—even disciples need divine protection from spiritual danger.

Kingdom Crescendo: The Pattern Complete

This prayer moves from worship to warfare, from God’s glory to human need, from eternal to temporal concerns. Matthew’s six petitions provide comprehensive coverage; Luke’s five offer essential elements. But both establish the same hierarchy: God’s honor first, then human needs in proper order.

This is the grammar of kingdom living—relationship with God that prioritizes His glory while trusting His goodness for our needs.

Key Takeaways:

As Bereans, we should examine this teaching against Scripture (Acts 17:11). Here’s what stands firm:

- Two Accounts Confirm Core Elements – Matthew and Luke agree on the essential structure: relationship, worship, submission, provision, forgiveness, protection.

- Context Shapes Emphasis, Not Content – Matthew’s comprehensive version and Luke’s condensed version serve different teaching purposes but identical theological priorities.

- God’s Glory Always Precedes Human Need – Both versions begin with God-centered petitions before addressing personal concerns.

- Daily Dependence is Assumed – Whether “this day” or “each day,” both emphasize ongoing reliance rather than future security.

- Forgiveness is Reciprocal – Both connect receiving God’s forgiveness with extending forgiveness to others, though with different nuances.

- This is Model, Not Formula – Jesus teaches prayer patterns, not magic formulas—”pray like this” rather than “pray exactly this.”

- Prayer Requires Teaching – Luke’s context (disciples asking to learn) reminds us that effective prayer must be learned, not just attempted.

Timeline Note: Though Jesus had already taught this prayer publicly during the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 6), Luke’s account (Luke 11) captures a later, private moment—likely a year or more into His ministry. By then, the disciples had witnessed His prayer life repeatedly and were growing in spiritual hunger. It’s not incongruous that they would ask, “Teach us to pray,” even after hearing the model previously. Perhaps this wasn’t a request for repetition, but a desire for increased likeness.

Jesus, as a rabbi, often revisited core teachings in new contexts. The Sermon on the Mount likely occurred in the early Galilean phase of His ministry (circa 28 AD), while Luke’s account unfolds during His later Judean journey toward Jerusalem (circa 29–30 AD). Time, geography, and audience separate the two occasions—but unified in purpose: to shape kingdom prayer.

Editor’s Note: The Lord’s Prayer provides the master template in our prayer series. Where Paul demonstrates intercession for growth and Daniel models confession for cleansing, Jesus establishes the foundational pattern that encompasses worship, submission, provision, forgiveness, and protection. Having two Gospel accounts allows us to see both comprehensive instruction (Matthew) and essential elements (Luke).

Rather than personalizing this prayer (it’s already complete), we use it as the structural template for all our prayers:

The Kingdom Prayer Pattern: "Our Father in heaven [relationship], hallowed be your name [worship]. Your kingdom come, your will be done [submission]. Give us daily bread [provision]. Forgive us as we forgive others [cleansing]. Lead us not into temptation [protection]."

This pattern can guide any prayer, ensuring we maintain kingdom priorities: God’s glory first, then our needs in proper biblical order. Whether following Matthew’s fuller version or Luke’s essential elements, the architecture remains the same—and it’s the foundation upon which all other biblical prayers are built.

For a complete treatise on this prayer, see here: “Teach Us to Pray”