Let Every Person Be Subject…

The Bible treats leadership as a divine calling—structured, purposeful, and covenantal. It is never arbitrary. Every role that endures is designed to magnify Christ, to care for His flock, and to extend His kingdom until He comes again.

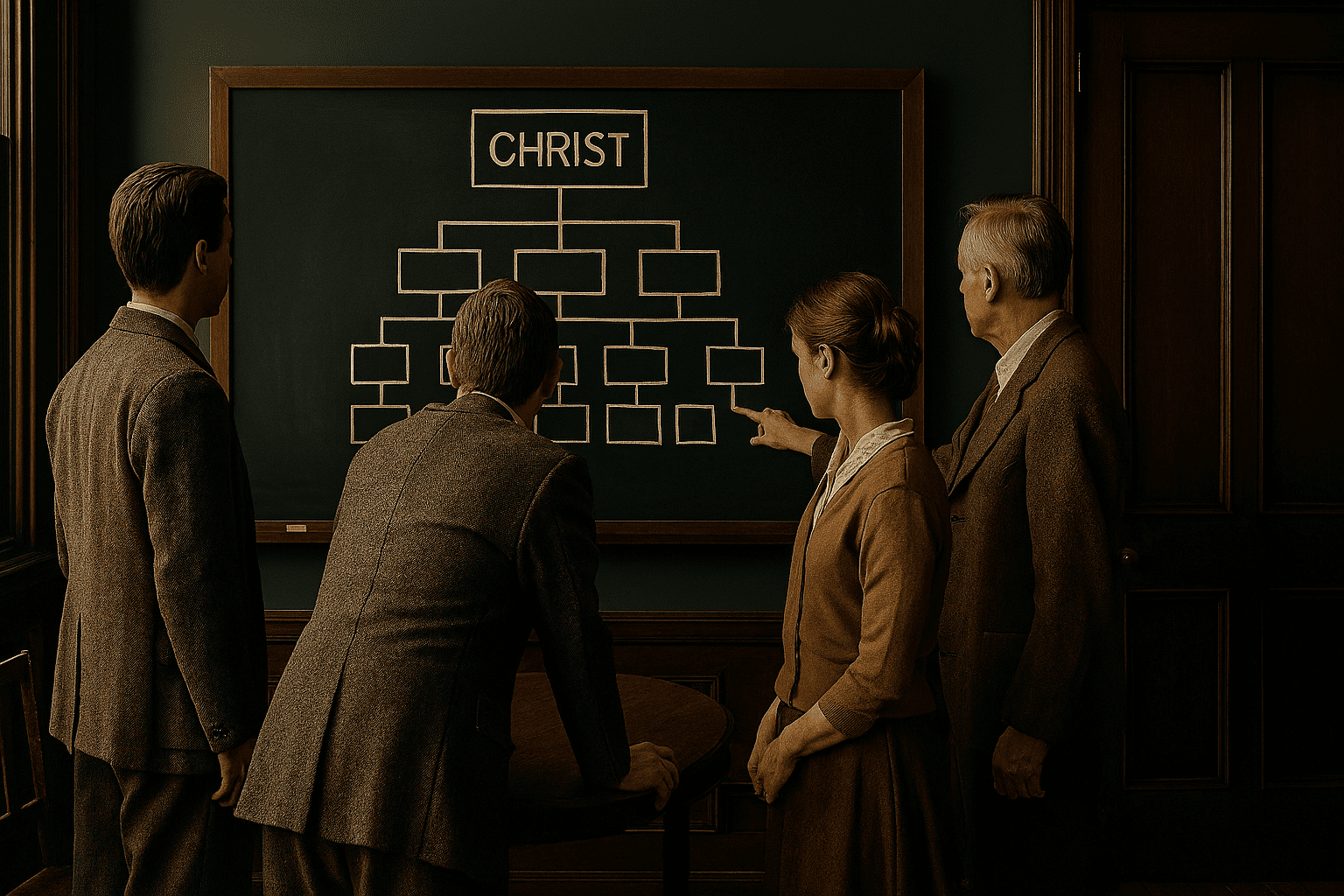

The divine architecture of biblical leadership

“Let every person be subject to the governing authorities. For there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been instituted by God.”

— Romans 13:1

Authority doesn’t begin with elections, charisma, or convenience; it begins with God. From patriarchs and prophets to elders and apostles, Scripture presents leadership as something appointed by heaven for the good of God’s people and the glory of God’s name. Whether holding a staff, unrolling a scroll, or carrying a servant’s towel, biblical leaders are chosen to reveal God’s character, uphold His covenant, and shepherd His people through wilderness, exile, and mission. In an age suspicious of power and weary of frauds, Scripture anchors us: true authority is not self-made; it is God-ordained.

Leadership as covenant and calling

The Bible treats leadership as a divine calling—structured, purposeful, and covenantal. It is never arbitrary. Under the Old Covenant, God raises judges to deliver, priests to mediate, kings to steward justice, and prophets to confront and comfort. Under the New Covenant, Christ fulfills temple and priesthood, then initiates a Spirit-empowered architecture: apostles who lay foundation by witness and doctrine, elders who shepherd local bodies, deacons who preserve unity through service, and gifted workers—evangelists, teachers, prophets—who build up Christ’s body. Across both Testaments, the roles are not ornamental; they are instruments of God’s redeeming work, tied to promises, tested by obedience, and defined by service. This article traces how each role comes to be, what its God-given purpose is, and why God established it—then clarifies contested questions around Judas, the Twelve, Paul, and the Seventy-Two for Berean clarity.

Stewardship before the fall, covenant after it

Leadership begins in a garden—before crowns and thrones—when God gives humanity dominion to cultivate, guard, and steward creation (Genesis 1:26–28; 2:15). Dominion is responsibility under God’s rule, not domination by human whims. After the fall, as sin fractures communion and corrodes trust, God answers chaos with covenant: He calls specific people into specific roles, not to concentrate power but to embody fidelity and care. The pattern is consistent: God appoints, Scripture defines, and fruit reveals.

Patriarchs: carriers of promise

Before Israel is a nation, it is a family. Abraham is not king; he is bearer of promise. God calls him from Ur with a mission that will bless the nations: “I will make you a great nation… and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed” (Genesis 12:2–3). Patriarchal leadership is familial, rooted in faith and promise, not institutional power. Isaac and Jacob inherit the covenant and the responsibility to trust, obey, and transmit a holy heritage. Their authority is relational—anchored in God’s speech and ratified by God’s faithfulness. Purpose: cradle and transmit the promise. Qualification: call and covenant fidelity. Why God established it: to form a people through whom blessing would come to all nations.

Prophets: covenant prosecutors and comforters

As Israel grows, God raises prophets—not as fortune tellers but as messengers who call people back to righteousness, justice, and mercy. Moses resists the call at the bush, but God says, “I will be with your mouth and teach you what you shall speak” (Exodus 4:12). Prophets speak for God, often against kings, reminding Israel of covenant obligations and exposing idolatry. Their authority is not inherited; it is bestowed by divine encounter and authenticated by truth: their words must align with God’s law and come to pass (Deuteronomy 13:1–5; 18:20–22). Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel indict injustice and comfort the remnant with promises of restoration. Purpose: confront rebellion, confirm promises, and call to repentance. Qualification: divine calling, doctrinal fidelity, and truthful words. Why God established it: to keep His people tethered to His character and covenant.

Priests and Levites: mediators of holiness

Priests are instituted to mediate between God and people. Aaron and his sons are consecrated with oil and blood, set apart to offer sacrifices, teach the law, and preserve holiness (Exodus 28–29; Leviticus 8–10; 21). Qualifications are strict: lineage from Aaron, physical integrity, moral sobriety. The priesthood is not a career; it is a calling that foreshadows the ultimate High Priest. Levites, though not priests, are appointed to assist in tabernacle and temple service, guard sacred things, carry the ark, and teach (Numbers 3–4; Deuteronomy 33:8–11). Together, they form Israel’s sacred infrastructure, ensuring worship is orderly, sacrifices rightly offered, and holiness central. Purpose: mediate access and instruction, embody holiness. Qualification: lineage and purity. Why God established it: to dwell among a holy people through ordered worship and atoning sacrifice until fulfillment in Christ.

Judges: Spirit-empowered deliverers

In the pre-monarchic era, judges arise in crises. They are not elected; they are raised up. “Then the Lord raised up judges, who saved them out of the hand of those who plundered them” (Judges 2:16). Deborah, Gideon, and Samson are empowered by the Spirit to deliver Israel, administer justice, and restore covenant faithfulness. Their leadership is occasional and time-bound—divine intervention in seasons of oppression and apostasy. They do not build dynasties; they rescue a people to return them to God. Purpose: deliver and restore. Qualification: God’s raising and Spirit empowerment. Why God established it: to interrupt cycles of sin with mercy and justice.

Kings: covenant stewards under law

Eventually, Israel demands a king “like the nations.” God grants the request but sets conditions: the king must not multiply horses, wives, or wealth; must write his own copy of the law; must fear the Lord and keep His statutes (Deuteronomy 17:14–20). Saul is chosen but falters, exposing the danger of pride. David—shepherd, psalmist, warrior—becomes the archetype of covenant kingship, and God makes with him a promise: a son whose kingdom will be everlasting (2 Samuel 7). The monarchy in Israel is never absolute; it is tethered to Torah and subject to prophetic rebuke. Even Solomon, in wisdom, stumbles when he forgets the source and boundaries of his authority. Purpose: steward justice, protect the people, uphold law. Qualification: covenant fidelity and humility. Why God established it: to provide ordered governance under His law while pointing to the true King.

The New Covenant: fulfillment, transformation, initiation

With the coming of Christ, leadership is clarified and reordered. The veil is torn. The temple is no longer central; the Church becomes the temple. The Levitical priesthood is fulfilled and rendered obsolete, because the once-for-all sacrifice has been offered by the true High Priest (Hebrews 7–10). Authority shifts from hereditary, temple-centered offices to Spirit-gifted, grace-based leadership—given to build up the body of Christ.

The Twelve: chosen, commissioned, configured to Israel’s story

Jesus spends the night in prayer, then chooses twelve from among His disciples and names them apostles (Luke 6:12–13). The number is not incidental; it signals a new Israel. Just as twelve tribes formed the covenant people, twelve apostles are appointed to sit on thrones, judging the twelve tribes (Luke 22:30; Matthew 19:28). The Twelve are foundational witnesses: they accompany Jesus from the baptism of John through His ministry; they see Him risen; they are sent to preach, baptize, and teach all He commanded (Matthew 28:18–20; Acts 1:21–22). Their authority is unique and their role unrepeatable as a closed, symbolic circle bound to the reconstitution of God’s people around Jesus.

Judas: chosen, yet a betrayer—no mistake, but fulfillment

Judas Iscariot is included among the Twelve. This was not an oversight. “Jesus knew from the beginning who those were who did not believe, and who it was who would betray him” (John 6:64). Later, He says, “Did I not choose you, the Twelve? And yet one of you is a devil” (John 6:70). Judas’s inclusion fulfills Scripture—“He who ate my bread has lifted his heel against me” (Psalm 41:9; cited in John 13:18)—and serves God’s sovereign purposes. His proximity to Jesus for three years underscores Christ’s innocence and warns the Church: ministry activity and reputation are not substitutes for true faith. Judas’s apostleship was real, but his betrayal shows divine calling does not override human responsibility. Jesus did not err; Judas fulfilled prophecy and revealed the peril of hypocrisy.

The vacancy and Matthias: restoration by prayerful discernment

Judas’s defection creates a wound that must be healed, not merely for administrative completeness but for symbolic integrity. Peter stands among the disciples after the ascension and explains: Judas “turned aside to go to his own place,” and “his office let another take” (Acts 1:20). The word “office” (episkopē) signals a real, divinely instituted stewardship requiring a faithful servant. The replacement must have accompanied Jesus from John’s baptism to the ascension and must be a witness of His resurrection (Acts 1:21–22). Two men are proposed—Joseph called Barsabbas (Justus) and Matthias. The community prays, entrusting the decision to the Lord who knows hearts: “Show us which of these two you have chosen” (Acts 1:24). Then they cast lots, a practice in Israel symbolizing surrender to God’s decision: “The lot is cast into the lap, but its every decision is from the LORD” (Proverbs 16:33). This was not divination but prayerful submission to divine sovereignty—and God, who has a clear pattern of intervening when His people err (Jonah, Balaam, Abraham at Moriah), gave no correction. The lot falls to Matthias, and he is numbered with the eleven apostles (Acts 1:26). The Twelve are restored before Pentecost—before Paul’s conversion on the Damascus road years later—ready to testify together as a complete witness. Matthias is not a consolation prize; he is God’s choice—prayed for, qualified, and added to the witness. Scripture records no controversy, no correction, no competing claim.

Why Matthias Stands

Paul’s Own Testimony: Paul acknowledges “the Twelve” as a completed group (1 Corinthians 15:5), describes himself as coming “last of all” and “untimely born” (15:8), and never claims Matthias’s place should have been his.

Sovereign Method: The lot-casting was preceded by prayer (Acts 1:24) and grounded in Scripture’s affirmation that “every decision [of the lot] is from the LORD” (Proverbs 16:33).

Divine Silence as Confirmation: God has a pattern of correcting His people’s errors (Jonah, Balaam, Abraham). No correction appears regarding Matthias—only his simple inclusion among the apostles (Acts 1:26).

Disciple versus apostle: a crucial distinction for clarity

A disciple (mathētēs) is a learner, follower, student of Jesus. In the Gospels, “disciple” refers broadly to those who follow Jesus, including women (Luke 8:1–3). After Pentecost, all believers are called disciples (Acts 6:1). An apostle (apostolos) is literally “one who is sent”—a commissioned emissary with authority. Jesus chose twelve disciples and designated them apostles (Luke 6:13). Every apostle is a disciple, but not every disciple is an apostle. Discipleship is the broad call to follow Jesus; apostleship is the narrower office of being sent with His authority to bear foundational witness and establish the Church.

The Seventy(-Two): ordinary disciples sent with extraordinary authority

Luke 10 records Jesus sending seventy (or seventy-two, depending on manuscripts) disciples in pairs. Unlike the Twelve, they are not named. Their mission is to heal, proclaim the kingdom, and prepare towns for Jesus’ arrival. Their anonymity is instructive: they represent the broader body of disciples, ordinary followers entrusted with extraordinary mission. Their joy—“Lord, even the demons are subject to us in your name!” (Luke 10:17)—shows that authority in Christ is not limited to the Twelve. Jesus rejoices, yet redirects their joy: “Do not rejoice in this, that the spirits are subject to you, but rejoice that your names are written in heaven” (Luke 10:20). Leadership gifts are tools; sonship is the treasure.

Paul: apostle “as one untimely born”—equal in authority, distinct in appointment

After the Twelve are restored, the risen Christ appears to another man—on a road, in blinding glory, interrupting a life of zeal opposed to the Church. “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting,” He says to Saul of Tarsus (Acts 9:5). Ananias is sent to him with a commission: Saul is a “chosen instrument” to carry Christ’s name before Gentiles, kings, and the children of Israel (Acts 9:15–16). Paul later insists: “Paul, an apostle—not from men nor through man, but through Jesus Christ and God the Father” (Galatians 1:1). Yet notably, Paul never disputes Matthias’s selection or claims to be “the rightful twelfth.” Instead, he acknowledges “the Twelve” as a distinct, completed group to whom Christ appeared (1 Corinthians 15:5), and describes himself as “last of all… as to one untimely born” (1 Corinthians 15:8)—an apostle after and beyond the Twelve, not in place of one. He received the gospel by revelation (Galatians 1:12), saw the risen Lord (1 Corinthians 9:1), and was taken up into visions too wondrous for words (2 Corinthians 12:1–6). He describes himself as “the least of the apostles,” yet he labors more than any—“not I, but the grace of God that is with me” (1 Corinthians 15:9–10).

How does Paul fit with the Twelve? He does not replace Judas; Matthias did that—before Paul’s conversion even occurred. Paul never argues he should have been numbered among them. He is not one of the Twelve who accompanied Jesus in His earthly ministry. Yet he is an apostle of Christ, bearing equal authority and recognition among the apostolic leadership. In Jerusalem, those “reputed to be pillars”—James, Cephas (Peter), and John—extend the right hand of fellowship to Paul and Barnabas, recognizing Paul’s call “to the Gentiles” as distinct but equal to Peter’s call “to the circumcised” (Galatians 2:7–9). Paul submits his gospel to them “lest I had run in vain” (Galatians 2:2), not due to lack of Christ’s commissioning, but to protect unity and confirm truth. The Church thus holds two categories in tandem: the Twelve as foundational witnesses tied to Israel’s story, and other apostles personally commissioned by the risen Christ for mission beyond Jerusalem. If the Twelve signify restored Israel, Paul signifies the Church’s centrifugal mission—the Abrahamic blessing now realized and poured out among the nations.

Barnabas and the wider apostolic band: Spirit-sent, church-affirmed

Barnabas—“son of encouragement”—is set apart by the Holy Spirit, with Saul, in the church at Antioch: “Set apart for me Barnabas and Saul for the work to which I have called them” (Acts 13:2). With prayer, fasting, and laying on of hands, the church sends them. Luke later refers to “the apostles Barnabas and Paul” (Acts 14:14). The term “apostle” can refer both to the Twelve and to Christ-sent emissaries beyond the Twelve. James, the Lord’s brother, is called an apostle in a broader sense by Paul (Galatians 1:19). Silas, Timothy, and others function in apostolic teams. Scripture distinguishes between a closed, symbolic circle (the Twelve) and an open category of Christ-commissioned emissaries (apostles) extending the mission. This clarifies the “oddity” of Paul after Matthias: there is no contradiction, only distinction. Matthias restored the Twelve; Paul was added as Christ’s apostle to the Gentiles, validated by revelation, suffering, and fruit.

Elders and overseers: shepherds who guard doctrine and souls

As apostles plant churches, they appoint elders in every city (Acts 14:23; Titus 1:5). Elders (presbyteroi) and overseers (episkopoi) are two terms for the same role in the New Testament, emphasizing maturity and responsibility. Qualifications are rigorous: above reproach, faithful in marriage, sober-minded, hospitable, able to teach, not violent, not greedy, managing household well (1 Timothy 3:1–7; Titus 1:5–9). Their task is shepherding: feeding the flock with sound doctrine, protecting against wolves, correcting error, and modeling righteous living (Acts 20:28–31; 1 Peter 5:1–4). The authority of elders is pastoral and doctrinal; it is not authoritarian. They lead by teaching, example, and care, under the Chief Shepherd. Purpose: shepherd and guard. Qualification: character and competence in teaching. Why God established it: to provide ongoing, local care and doctrinal stability.

Deacons: dignified servants who preserve unity and care for need

When a practical crisis threatens unity—Greek-speaking widows overlooked in daily distribution—the apostles propose appointing seven reputable, Spirit-filled men to handle the work so the apostles can devote themselves to prayer and the Word (Acts 6:1–6). Though “deacon” (diakonos) is not used in Acts 6, the role anticipates the established office in 1 Timothy 3:8–13: dignified, not double-tongued, not addicted to much wine, not greedy, holding the mystery of faith with a clear conscience, tested and blameless. Deacons are not junior elders; they are ministers of mercy and order, ensuring the church’s practical care matches its preached truth. Stephen, one of the seven, preaches with power and dies with glory; Philip, another, evangelizes Samaria and the Ethiopian. Service and proclamation are companions, not rivals. Purpose: meet tangible needs and guard unity. Qualification: tested character. Why God established it: to free word-ministry while dignifying and protecting the vulnerable.

Teachers, evangelists, and prophets: gifts for the Church’s growth

Christ gives gifts—apostles, prophets, evangelists, shepherds, teachers—to equip the saints for ministry and build up the body (Ephesians 4:11–13). Teachers instruct; evangelists herald good news; shepherds care; prophets speak Spirit-prompted words that edify and warn. The New Testament anchors these gifts in order: prophecy is tested; teaching is weighed; leadership is plural; and all is done decently and in order (1 Corinthians 14; 1 Timothy 4; Titus 2). Gifts are not titles to wield; they are graces to steward. Purpose: maturation and unity. Qualification: Spirit-gifting, tested words, faithful lives. Why God established it: to build a healthy, truth-anchored, mission-advancing Church.

What the New Covenant closes—and what it initiates

The New Covenant fulfills and ends specific roles by meeting their purpose in Christ.

- The Levitical priesthood ends because we have a great High Priest, Jesus, who offers the perfect sacrifice once for all and ever lives to intercede (Hebrews 7–10). In Him, all believers become a royal priesthood, offering spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God (1 Peter 2:5, 9). The priestly function remains—intercession, worship, holiness—but the office shifts from hereditary caste to the whole people of God in Christ.

- Animal sacrifices cease because Christ’s blood accomplishes true cleansing and reconciliation (Hebrews 10:1–18).

- Temple-centered worship ends because God’s presence dwells in the Church by the Spirit; believers are living stones built into a spiritual house (1 Corinthians 3:16–17; 6:19; 1 Peter 2:5).

- Monarchy as a theocratic institution tied to land and temple is not carried forward. Kingship is fulfilled in Christ, the Son of David, whose kingdom is not of this world (John 18:36) and whose rule is over all. Human leadership in the Church is pastoral, not royal; plural, not dynastic; accountable to Scripture and Spirit.

The New Covenant initiates or reframes leadership accordingly:

- Apostles establish foundation by witness and doctrine. The Twelve are unique as a closed circle; other apostles, like Paul and Barnabas, are Christ-sent emissaries for mission. The office is foundational, not perpetually inheritable in the form of the Twelve.

- Elders/overseers shepherd local churches as ordinary, ongoing leadership.

- Deacons serve practical needs to guard unity and dignity.

- Teachers, evangelists, and prophets function as gifts for edification, under tested order and pastoral oversight.

Purpose, qualifications, and God’s “why” behind every role

Across both covenants, God’s rationale for leadership is consistent: reveal His character, uphold His covenant, protect His people, and advance His mission.

- Prophets exist to speak God’s word, confront idolatry, and comfort the faithful. Qualifications center on God’s call, fidelity to Scripture, and truthfulness.

- Priests/Levites exist to mediate holiness—offering sacrifices, teaching law, guarding sacred space—anticipating Christ’s priesthood. Qualifications are lineage and purity.

- Judges exist to deliver and restore in times of crisis; qualification is God’s raising and the Spirit’s empowerment.

- Kings exist to steward justice under God’s law; qualification is covenant fidelity, not mere power.

- Apostles exist to witness, teach, and lay foundation; qualifications for the Twelve include historical presence and resurrection witness, while Paul’s and others include personal commissioning by the risen Christ, gospel truth, and fruit.

- Elders/overseers exist to shepherd and guard; qualifications are character and competence in teaching.

- Deacons exist to serve needs and preserve unity; qualifications are character and tested faith.

- Teachers/evangelists/prophets exist to build up the Church; qualifications are Spirit-gifting, tested words, and faithful lives.

Why does God establish roles? Because order serves love. Structure guards holiness. Authority, rightly ordered, protects the vulnerable, checks error, and channels grace. God’s “why” is pastoral: He appoints leaders to serve, not to be served; to lay down their lives, not to secure their legacy. The cruciform shape of leadership is the New Covenant’s signature: “The Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many” (Mark 10:45). Leaders mirror the Lamb, not the emperors.

The church’s posture: discernment, submission, and hope

If all authority comes from God, how does the Church live under imperfect leaders? The New Testament forms a posture: discernment regarding truth and life; submission within godly order; confrontation when leaders err; and hope anchored in Christ’s ultimate rule.

- Discernment tests teaching against Scripture and watches the life of leaders (Acts 17:11; 1 Timothy 4:16). False prophets and pretenders will arise; the Berean church learns, examines, and holds fast to what is good.

- Submission honors legitimate authority for the sake of unity, mission, and worship (Hebrews 13:17; 1 Thessalonians 5:12–13). Submission is not servility; it is ordered love under Christ’s headship.

- Confrontation corrects leaders when they deviate from the gospel (Galatians 2:11–14), always aimed at repentance and restoration. Authority is accountable, never absolute.

- Hope looks beyond all human offices to Christ, the Head of the Church, whose authority is perfect, whose care is unfailing, and whose kingdom cannot be shaken (Hebrews 12:28).

Weaving back to the contested questions: Judas, Matthias, Paul, and the Seventy-Two

We can now address the pressing questions with clarity.

- Did Jesus make a mistake naming Judas as an apostle? No. Jesus chose Judas knowingly, and Judas’s betrayal fulfilled Scripture (John 6:64–70; Psalm 41:9; John 13:18). Judas’s inclusion exposes hypocrisy and underscores Christ’s innocence, becoming a sober warning to the Church.

- Why was Matthias necessary if Paul would later be called? Because the Twelve are a symbolic, closed circle tied to Israel’s story and the promised judgment of the twelve tribes (Matthew 19:28; Luke 22:30). Matthias restores the circle before Pentecost—and chronologically before Paul’s conversion. Paul’s apostleship is distinct—Christ’s direct appointment to extend the mission to the Gentiles—equal in authority but different in category from the Twelve. Paul himself never contested this: he defends his apostleship despite not being one of the Twelve (Galatians 2; 2 Corinthians 11-12), not because he should have been counted among them.

- How do disciple and apostle relate? Discipleship is the broad call to follow Jesus; apostleship is the narrower commission to be sent with His authority. Every apostle is a disciple; not every disciple is an apostle.

- What is the role of the Seventy(-Two)? They represent ordinary disciples sent in mission with real authority under Christ’s name (Luke 10). Their work proves that power in ministry is not confined to office; it is distributed by Christ through the Spirit to the wider body.

In short, the New Testament’s leadership architecture is coherent, not contradictory: the Twelve signify reconstituted Israel; Matthias restores the symbol; Paul and others extend the mission; elders and deacons sustain local care; teachers, evangelists, and prophets grow the body; and all disciples participate in the life and work of the kingdom.

Back to the beginning, with clarified sight

We return to Romans 13:1—no longer as a blunt instrument, but as a bright lens. Authority, in all its forms, is from God. Whether prophetic or priestly, judicial or royal, apostolic or pastoral, leadership in Scripture is never self-appointed. It is God-ordained, covenant-bound, and Spirit-empowered. The Twelve stand as foundation stones of a renewed people; Judas’s tragedy warns against hollow discipleship; Matthias’s selection restores symbolic integrity; Paul strides across nations as Christ’s emissary; elders and deacons quietly guard and serve the flock; and the Seventy-Two remind us that ordinary disciples carry extraordinary grace. Through them all, the true Leader remains the Lord—whose cross defines authority, whose Spirit empowers service, and whose promises secure a kingdom where justice and mercy meet.

In an age that distrusts power, the Bible gives something better than cynicism: a vision of leadership that is holy, humble, and hopeful. Appointed by heaven, these roles do not exalt men; they exalt God. And that—always and forever—is the point.

Editor’s Note: What Remains for Us Today?

When Christ fulfilled the Old Covenant, He did not leave His people leaderless or adrift. The temple curtain was torn, the sacrifices ceased, and the Levitical priesthood found its completion in Him. Yet in place of those shadows, God has given us something better—roles and callings that remain for the health of His Church until the day Christ returns.

The Temple is no longer a building of stone in Jerusalem. You, the people of God, are the temple. Paul reminds us, “Do you not know that you are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in you?” (1 Corinthians 3:16). Every believer is a living stone, joined together into a dwelling place for God by the Spirit (Ephesians 2:21–22). This means holiness is not confined to sacred geography—it is carried in the lives of God’s people wherever they go.

The High Priest is no longer a man from Aaron’s line. There is only one, and His name is Jesus. He has entered the heavenly sanctuary once for all, securing eternal redemption (Hebrews 9:11–12). We do not need another mediator, for Christ Himself intercedes for us at the right hand of the Father (Romans 8:34). Our confidence rests not in human priests but in the perfect priesthood of Christ.

Evangelists remain as heralds of the good news. Like Philip in Acts 21:8, they are called to proclaim Christ where He is not yet known and to stir the Church to bold witness. Their work reminds us that the gospel is not meant to be hoarded but shared, and that every believer is called to bear witness, even if not all are evangelists by office.

Shepherds (Pastors/Elders) are given to care for the flock. Peter exhorts them, “Shepherd the flock of God that is among you… not domineering over those in your charge, but being examples to the flock” (1 Peter 5:2–3). Their authority is pastoral, not tyrannical; their model is the Good Shepherd who lays down His life for the sheep (John 10:11). In a world of fractured trust, faithful shepherds embody Christ’s care.

Deacons serve as dignified ministers of mercy. Their calling is to meet practical needs, preserve unity, and ensure that no one in the body is neglected (Acts 6:1–6; 1 Timothy 3:8–13). They remind us that service is not secondary—it is central to the life of the Church. In their quiet faithfulness, they reflect the humility of Christ who washed His disciples’ feet.

Elders (Overseers/Presbyters) continue as the ordinary, ongoing office of spiritual oversight in local congregations. They are charged to guard doctrine, nurture souls, and model maturity (Titus 1:5–9). Their authority is not about status but stewardship, not about control but care. They are under-shepherds, accountable to the Chief Shepherd.

And finally, Ambassadors—a title Paul gives not to a select few but to all believers. “We are ambassadors for Christ, God making his appeal through us” (2 Corinthians 5:20). This is not an office but an identity. Every Christian represents the King in word and deed, pleading with the world: “Be reconciled to God.”

So what are we left with today? Not a temple of stone, but a temple of people. Not a line of priests, but one eternal High Priest. Not kings on thrones, but shepherds and servants. Not sacrifices of bulls and goats, but the living sacrifice of holy lives (Romans 12:1). And not a closed circle of apostles, but a global body of ambassadors—disciples sent into the world with the gospel of reconciliation.

This is the architecture of leadership under the New Covenant: Christ as cornerstone, His people as the temple, and His Spirit equipping shepherds, servants, and heralds to build up the body. Every role that endures is designed to magnify Christ, to care for His flock, and to extend His kingdom until He comes again.