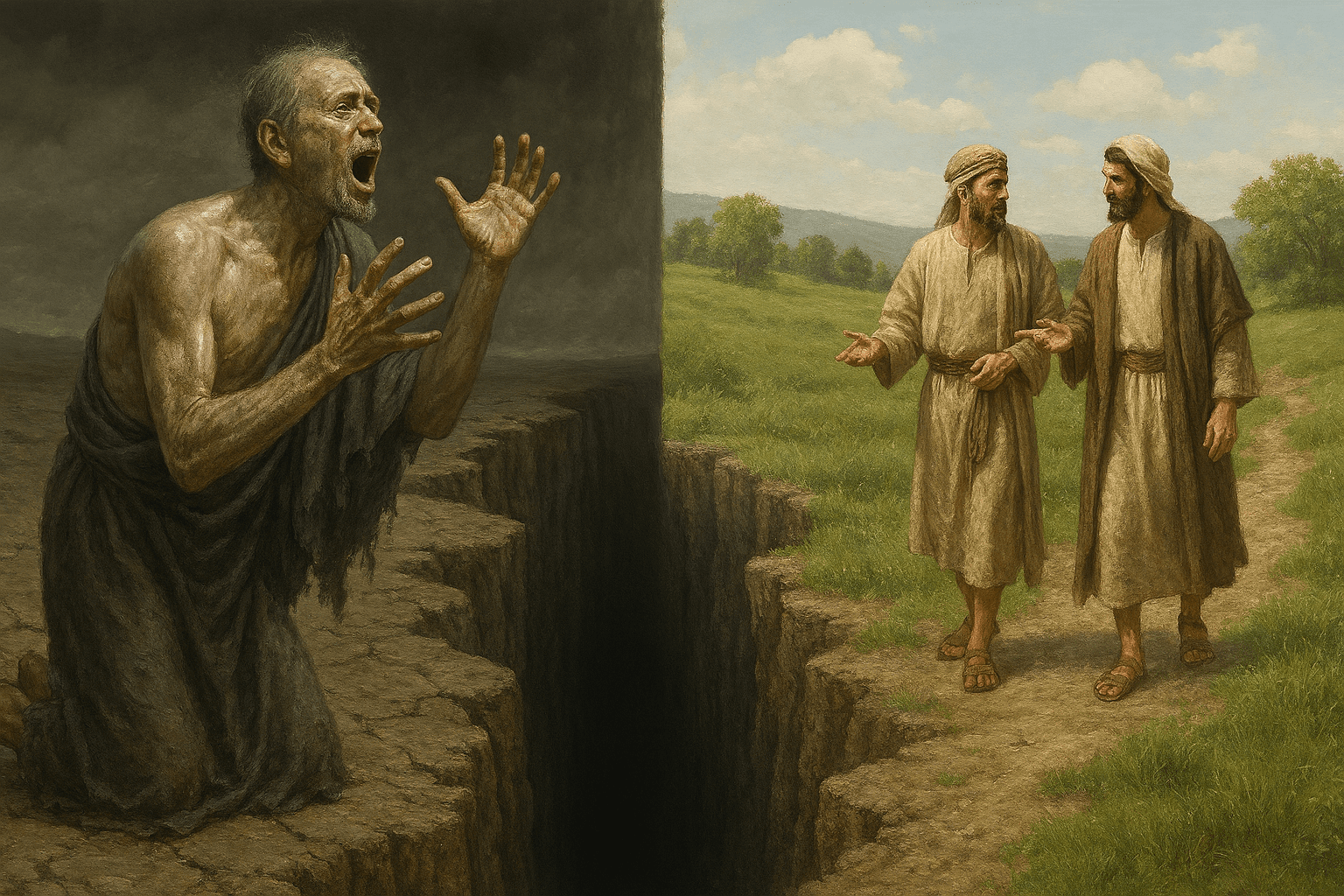

How did these men arrive at such different fates?

Two men, both dead, both conscious, eternally divided. Between them stretches a chasm that cannot be crossed. This is not mythology. This is Jesus’ parable teaching about the afterlife.

Where do we go from here?

“And in Hades, being in torment, he lifted up his eyes and saw Abraham far off and Lazarus at his side. And he called out, ‘Father Abraham, have mercy on me, and send Lazarus to dip the end of his finger in water and cool my tongue, for I am in anguish in this flame.’” (Luke 16:23–24, ESV)

Two men, both dead. One is in torment, conscious, aware, pleading. The other is comforted at Abraham’s side, silent, received. Between them stretches a great chasm, fixed and impassable. The rich man can see Lazarus. He can remember his life. He can speak, reason, and beg for mercy. But he cannot cross. He cannot escape. He cannot change his destiny. Death has sealed it.

This is not mythological allegory borrowed from pagan cosmology. This is Jesus’ teaching through parable—using narrative elements to reveal theological truths about the afterlife, the intermediate state between death and resurrection—and He refuses to soften the reality. The dead are conscious. The righteous and the wicked are separated. The destinies are irreversible. And the Scriptures that could have saved the rich man in life are the very Scriptures that now testify against him in death.

How did these two men arrive at such different fates? The backstory is brief and devastating. In life, there was a rich man “who was clothed in purple and fine linen and who feasted sumptuously every day. And at his gate was laid a poor man named Lazarus, covered with sores, who desired to be fed with what fell from the rich man’s table” (Luke 16:19–21, ESV). Wealth insulated from need. Comfort blind to suffering. Privilege deaf to the cries at its own doorstep. Then death came for both: “The poor man died and was carried by the angels to Abraham’s side. The rich man also died and was buried” (Luke 16:22, ESV). Death is the great equalizer. It strips away illusions, pretensions, and the false securities we cling to in this age. And it reveals where every soul will go.

Jesus does not let death dissolve into vagueness or sentimentality. He takes us behind the veil. He shows us Hades—the realm of the dead. He shows us Paradise—Abraham’s side. He shows us consciousness, memory, anguish, comfort, and the unbridgeable chasm between them. This is not the final judgment. This is not the lake of fire. This is not the resurrection. This is the intermediate state—the realm of the dead between death and the day of Christ’s return. And Jesus uses it to force a question we would rather avoid: What actually happens to every human being the moment they die? And what happens after that?

Eternal Destinies as Scripture Presents

If all humanity dies—the righteous and the wicked, the elect and the reprobate—then where do they go? What is Sheol? What is Hades? What is Paradise? What is Gehenna? What is the lake of fire? What is the resurrection? What is the second death? And perhaps most pressing: Is the final state of the wicked conscious or unconscious? Eternal or temporary? Punitive or annihilating?

Jesus’ parable refuses to let us sentimentalize the afterlife. Scripture refuses to let us flatten it into vague reassurances or wishful thinking. And the canon gives us a coherent, unavoidable architecture: a conscious intermediate state, a universal resurrection, a final judgment, and an eternal, embodied destiny—either in the New Heavens and New Earth or in the second death, the lake of fire (Revelation 20:14–15; 21:1–4). This is not mythology. This is not speculation. This is biblical eschatology—the doctrine of last things—delivered with clarity and severity.

This article interrogates each stage, each term, each state, and each eventuality—not to satisfy curiosity but to confront the reality Jesus insists we face before we die. We will examine what constitutes human personhood and what death separates. We will map the complete biblical vocabulary for death and the afterlife. We will explore the intermediate state as Scripture describes it, the resurrection as Scripture promises it, the judgment as Scripture declares it, and the eternal destinies as Scripture refuses to soften them. We will test popular assumptions about the afterlife against the canonical witness, asking not what we wish were true but what God has revealed to be true.

The Intermediate State: Conscious, Divided, Waiting

The moment a human being dies, Scripture says they enter the realm the Old Testament calls Sheol—שְׁאוֹל, the place of the dead—and the New Testament calls Hades—ᾍδης, its Greek equivalent. These terms—though they share vocabulary with ancient Near Eastern and Greco-Roman cosmology—are filled by Scripture with distinct theological meaning. In the Old Testament, Sheol carries broad semantic range: the grave itself, the realm of all the dead, poetic metaphor for death, sometimes covenantal judgment. By the New Testament period, Hades (the Greek equivalent) becomes more specifically associated with the intermediate state—the conscious condition of the dead awaiting resurrection and final judgment. Jesus’ parable uses this developed understanding to reveal what lies beyond death. And Jesus’ parable in Luke 16 is the most detailed narrative window Scripture gives us into that realm, though other texts—Luke 23:43, Philippians 1:23, 2 Corinthians 5:8, Revelation 6:9-11—provide equally vital testimony to conscious intermediate existence.

The first thing we notice is consciousness. The rich man lifts his eyes. He speaks. He remembers his five brothers. He reasons. He pleads. He experiences anguish—odunaomai (ὀδυνάομαι), a term denoting intense physical and emotional suffering. He is not asleep. He is not annihilated. He is not dissolved into non-being. He is awake, aware, and in torment. And Lazarus, though silent in the narrative, is portrayed as comforted, received, carried to Abraham’s side—literally “Abraham’s bosom,” kolpos (κόλπος), a term denoting intimate fellowship and the place of honor at a banquet, evoking the beloved disciple reclining on Jesus’ chest at the Last Supper (John 13:23). The word suggests not merely location but relationship, comfort, and honored proximity to the covenant father.

And this waiting place is divided. Abraham explains the division explicitly: “Between us and you a great chasm has been fixed, in order that those who would pass from here to you may not be able, and none may cross from there to us” (Luke 16:26, ESV). The righteous are comforted; the wicked are in anguish. The chasm between them is fixed—not by geography but by the irreversible judgment of God. No one crosses. No one switches sides. No one negotiates. No one bargains. The destinies are sealed, not because God is cruel but because death is the boundary God has set for repentance. Scripture establishes this principle explicitly: “It is appointed for man to die once, and after that comes judgment” (Hebrews 9:27, ESV). The author of Hebrews writes this in the context of Christ’s once-for-all sacrifice, contrasting the repeated rituals of the old covenant with the finality of Christ’s death and the finality of human death as the threshold beyond which no further opportunity for repentance exists. Jesus’ parable in Luke 16 illustrates this irreversibility through the fixed chasm—the narrative embodies the doctrinal principle Hebrews declares.

But what of the objection that this is merely a parable, a story not meant to be taken literally? Jesus’ parables use symbolic elements to teach real truths. The prodigal son is not a historical figure, but the father’s love and the son’s repentance reflect real theological realities (Luke 15:11–32). Similarly, Jesus uses narrative elements in Luke 16—Abraham as speaker, Lazarus as exemplar, the rich man as cautionary figure—to teach about the real structure of the afterlife. The dialogue is representative. The geography is parabolic. The theology is binding. To dismiss the parable’s teaching about consciousness, division, and irreversibility because it is a parable is to misunderstand how Jesus teaches. He uses stories to reveal truths we could not otherwise see.

What Dies and What Remains: The Constitution of Human Personhood

Before we can understand where we go when we die, we must understand what we are. What constitutes a human being? Are we merely physical bodies animated by chemical processes, destined to dissolve into unconsciousness at death? Are we immaterial souls temporarily trapped in flesh? Or are we something more complex—a unity of body and soul, both essential to our humanity?

Scripture’s answer is clear: human beings are embodied souls. We are not bodies that happen to have souls, nor are we souls that happen to inhabit bodies. We are both, inseparably designed by God to exist as integrated wholes. When God created Adam, He “formed the man of dust from the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living creature” (Genesis 2:7, ESV). The Hebrew term translated “living creature”—nephesh chayyah (נֶפֶשׁ חַיָּה)—literally means a living soul or being. Adam became a living soul when the material (dust) and the immaterial (breath of God) were united. This is the constitution of human personhood: body and soul together.

Death, then, is the unnatural rupture of this unity. When Rachel dies, the text says “her soul was departing (for she was dying)” (Genesis 35:18, ESV). James defines death precisely: “The body apart from the spirit is dead” (James 2:26, ESV). Death is not the annihilation of the person. Death is the separation of body and soul. The body returns to dust (Genesis 3:19; Ecclesiastes 12:7). The soul—the immaterial, conscious self—returns to God who gave it (Ecclesiastes 12:7). This return is not necessarily to fellowship or communion; Ecclesiastes speaks of all souls returning to God’s jurisdiction, to stand under His authority, whether for judgment or for blessing. The wicked return to God as Judge; the righteous return to God as Father.

This is why the intermediate state is conscious. The soul does not cease to exist when it separates from the body. When Jesus tells the thief on the cross, “Today you will be with me in Paradise” (Luke 23:43, ESV), He is not promising bodily resurrection that very day. He is promising conscious fellowship in Paradise—the thief’s soul with Christ’s soul—while their bodies remain dead. When Stephen prays, “Lord Jesus, receive my spirit” (Acts 7:59, ESV), he is commending his immaterial self to Christ, knowing that his body will be stoned to death but his soul will be received into Christ’s presence. When Paul says, “We would rather be away from the body and at home with the Lord” (2 Corinthians 5:8, ESV), he is describing the soul’s conscious existence in God’s presence even while the body lies in the grave awaiting resurrection.

But the intermediate state is not the final state. Why? Because human beings are designed to be embodied. The soul without the body is incomplete. This is not to say the soul in Paradise is miserable—Paul calls it “far better” than this life (Philippians 1:23, ESV)—but it is to say that the soul in Paradise is not in its final, intended state. God did not create us as pure spirits. He created us as embodied beings, and His plan of redemption includes the redemption of the body, not merely the salvation of the soul.

This is why the resurrection is necessary. The soul in the intermediate state is conscious, blessed (if in Paradise), or tormented (if in Hades), but it is waiting. Waiting for what? For the reunion of body and soul. For the resurrection of the dead. For the restoration of full human personhood. When Christ returns, “the dead in Christ will rise first” (1 Thessalonians 4:16, ESV). The souls in Paradise will be reunited with their bodies—not the old, corrupted, mortal bodies they left behind, but new, glorified, immortal bodies fit for the New Creation (1 Corinthians 15:42–44). And the souls in Hades will likewise be reunited with their bodies—raised to stand before the judgment seat and then cast, body and soul together, into the lake of fire (Matthew 10:28; Revelation 20:13–15).

This is why Jesus says we should “fear him who can destroy both soul and body in hell” (Matthew 10:28, ESV). The final judgment is not merely spiritual. It is embodied. The wicked are not disembodied spirits floating in torment. They are raised, body and soul reunited, to face judgment and enter eternal punishment as whole persons—just as the righteous are raised, body and soul reunited, to enter eternal life as whole persons.

The modern tendency is to think of death as the end of personhood because we equate personhood with physical presence. We see the body in the casket, lifeless, and we assume the person is gone. But Scripture says otherwise. The body is dead, yes. The soul has departed, yes. But the person—the conscious, accountable, remembering self—continues. The rich man in Hades is still the rich man. He remembers his life. He knows he has five brothers. He reasons. He pleads. He suffers. He is not annihilated. He is separated from his body, awaiting the resurrection and the judgment.

And this is the terror of the second death: it is not unconsciousness. It is not the mercy of oblivion. It is the eternal, conscious, embodied existence of the wicked in separation from God, in the lake of fire, with no hope of escape, no possibility of repentance, no end to the torment. The body and soul that sinned together will suffer together. The body and soul that rejected Christ together will be rejected together. This is the justice of God: sin is punished in the same constitution in which it was committed.

And this is the hope of the gospel: salvation is not escape from embodiment but the redemption of embodiment. Christ did not come to free us from our bodies. He came to redeem our bodies (Romans 8:23). He did not come to make us disembodied spirits. He came to raise us from the dead, body and soul reunited, to live forever in the New Heavens and New Earth, where we will worship God face to face, in resurrected bodies that never decay, in a world where death has been swallowed up in victory (1 Corinthians 15:54).

This is what we are: embodied souls, created for eternity, awaiting resurrection, destined for judgment, and called to repent and believe before death separates what God has joined together.

Mapping the Biblical Vocabulary: Every Term for Every State

Before we proceed further, we must map the complete biblical vocabulary for the afterlife. Scripture uses distinct terms for distinct realities, and conflating them leads to confusion. The intermediate state is not the final state. Hades is not Gehenna. Paradise is not the New Heavens and New Earth. Let us trace each term, count its occurrences, and locate its proper place in the biblical architecture of death and eternity.

Sheol (שְׁאוֹל) appears 65 times in the Hebrew Old Testament. It is the realm of the dead, the grave, the pit, the place where all who die descend. Jacob expects to go down to Sheol mourning for Joseph (Genesis 37:35). Hannah prays that the Lord brings down to Sheol and raises up (1 Samuel 2:6). The Psalmist cries out for deliverance from Sheol (Psalm 86:13). Isaiah mocks the king of Babylon, saying Sheol beneath is stirred up to meet him when he comes (Isaiah 14:9). Job longs for Sheol as a hiding place from affliction (Job 14:13). The term is morally neutral in the Old Testament—both righteous and wicked go to Sheol. It is simply the place of the dead, awaiting resurrection and judgment.

Hades (ᾍδης) appears 10 times in the New Testament, translating the Hebrew Sheol into Greek. Jesus declares that the gates of Hades will not prevail against His church (Matthew 16:18). He warns Capernaum that it will be brought down to Hades for rejecting Him (Matthew 11:23; Luke 10:15). In the parable of the rich man and Lazarus, the rich man is in Hades, in torment, while Lazarus is at Abraham’s side (Luke 16:23). At Pentecost, Peter quotes Psalm 16, declaring that God did not abandon Christ’s soul to Hades (Acts 2:27, 31). In Revelation, Death and Hades are personified as riders (Revelation 6:8), and at the final judgment, Death and Hades give up their dead and are themselves thrown into the lake of fire (Revelation 20:13–14). Like Sheol, Hades is the intermediate holding place for the dead. It is not the final hell. It is temporary. It will be emptied at the resurrection and destroyed at the final judgment.

Paradise (παράδεισος) appears 3 times in the New Testament. Jesus promises the repentant thief on the cross, “Today you will be with me in Paradise” (Luke 23:43, ESV). Paul speaks of being caught up to the third heaven, into Paradise, and hearing things that cannot be told (2 Corinthians 12:3–4). John hears Christ promise the church in Ephesus, “To the one who conquers I will grant to eat of the tree of life, which is in the paradise of God” (Revelation 2:7, ESV). The term derives from the Persian word for a royal garden or enclosed park, and it evokes Eden, the garden of God. In Jewish thought, Paradise became a term for the abode of the righteous dead, awaiting resurrection. Jesus uses it to describe the same reality as ‘Abraham’s side’—the comfort side of the intermediate state for believers, expressed through both Jewish covenant imagery (Abraham) and broader biblical restoration imagery (Paradise as renewed Eden). Paradise is not yet the New Creation, but it is conscious, blessed fellowship with Christ while awaiting the resurrection.

Gehenna (γέεννα) appears 12 times in the New Testament, all but one in the words of Jesus (the exception is James 3:6). Jesus warns that it is better to enter life maimed than to be thrown into Gehenna, “where their worm does not die and the fire is not quenched” (Mark 9:43–48, ESV). He tells the Pharisees they are sons of hell—literally, sons of Gehenna (Matthew 23:15). He warns that whoever says “You fool!” will be liable to the hell of fire—Gehenna (Matthew 5:22). He commands us to fear not those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul, but rather to fear Him who can destroy both soul and body in Gehenna (Matthew 10:28). The term derives from the Valley of Hinnom (Ge-Hinnom in Hebrew), a ravine south of Jerusalem where Israel once burned children as sacrifices to Molech (2 Kings 23:10; Jeremiah 7:31). By Jesus’ day, Gehenna had become a symbol of divine judgment and final punishment. Gehenna is not Hades. Gehenna is the final hell, the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels (Matthew 25:41), into which the wicked will be cast after the resurrection and final judgment.

The Lake of Fire appears 5 times in Revelation, always in the context of final judgment (Revelation 19:20; 20:10, 14, 15; 21:8). The Beast and the False Prophet are thrown alive into the lake of fire that burns with sulfur (Revelation 19:20). The devil is thrown into the lake of fire where the Beast and the False Prophet are, and they are tormented day and night forever and ever (Revelation 20:10). Death and Hades are thrown into the lake of fire, and this is explicitly called “the second death” (Revelation 20:14). Anyone whose name is not found in the book of life is thrown into the lake of fire (Revelation 20:15). The cowardly, faithless, detestable, murderers, sexually immoral, sorcerers, idolaters, and all liars—their portion is in the lake that burns with fire and sulfur, which is the second death (Revelation 21:8). The lake of fire is Revelation’s term for the same final reality Jesus calls Gehenna. It is the final, eternal, conscious punishment of the wicked. It is not Hades. Hades is temporary; the lake of fire is eternal.

Tartarus (ταρταρόω) appears once in the New Testament. Peter writes that God did not spare the angels when they sinned, but cast them into Tartarus—tartaroō (ταρταρόω)—and committed them to chains of gloomy darkness to be kept until the judgment (2 Peter 2:4, ESV). The term is a verb, meaning “to cast into Tartarus,” and it refers to a place of imprisonment for fallen angels. In Greek mythology, Tartarus was the deep abyss below Hades where the Titans were imprisoned. Peter borrows the term to describe the place where sinning angels are held, awaiting final judgment. This is not the intermediate state for human beings. This is not Hades. This is a specialized holding place for rebellious angelic powers. Jude 6 confirms this, saying that angels who did not stay within their own position of authority are kept in eternal chains under gloomy darkness until the judgment of the great day.

The Abyss (ἄβυσσος) appears 9 times in the New Testament, primarily in Luke and Revelation. The demons beg Jesus not to command them to depart into the abyss—abussos (ἄβυσσος), the bottomless pit (Luke 8:31). Paul asks rhetorically, “Who will descend into the abyss?” to bring Christ up from the dead (Romans 10:7). In Revelation, the abyss is the prison from which the beast ascends (Revelation 11:7; 17:8), where the angel casts Satan and locks him for a thousand years (Revelation 20:1–3), and from which demonic locusts emerge to torment the earth (Revelation 9:1–11). The abyss is the realm of demonic confinement, a place of restraint for evil powers until the appointed time of their release or final judgment. It is not the lake of fire. It is not Gehenna. It is not Hades. It is a holding place for spiritual forces of evil.

The New Heavens and New Earth are the final dwelling place of the righteous, the eternal destiny of the redeemed. Isaiah prophesies their creation (Isaiah 65:17; 66:22). Peter promises that we are waiting for new heavens and a new earth in which righteousness dwells (2 Peter 3:13). John sees them in vision: “Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more” (Revelation 21:1, ESV). This is not Paradise. This is not Abraham’s side. This is not the intermediate state. This is the eternal state, the final dwelling place of God with man, where death shall be no more, neither shall there be mourning, nor crying, nor pain anymore (Revelation 21:3–4). The New Jerusalem descends from heaven, adorned as a bride for her husband (Revelation 21:2). The tree of life grows there, bearing twelve kinds of fruit (Revelation 22:2). The curse is removed. The servants of God worship Him face to face (Revelation 22:3–4). This is the goal of redemption, the completion of salvation, the restoration of Eden, the fulfillment of all God’s promises.

The biblical vocabulary is precise, and the canonical architecture is clear:

- Stage 1 – Death: Body and soul separate (James 2:26).

- Stage 2 – Intermediate State (now until resurrection): Sheol/Hades—the realm of the dead, divided into two sides: Paradise (Abraham’s side) for the righteous in conscious comfort, and the torment side for the wicked in conscious anguish. This is temporary, awaiting resurrection.

- Stage 3 – Resurrection (at Christ’s return): All are raised—body and soul reunited (John 5:28-29; 1 Thess 4:16; Rev 20:13).

- Stage 4 – Final Judgment: All stand before Christ. Works are judged. Destinies are declared (Rev 20:11-15).

- Stage 5 – Eternal Destinies: The righteous enter the New Heavens and New Earth in glorified bodies (Rev 21:1-4). The wicked are cast into Gehenna—the lake of fire, the second death—in resurrected bodies, for eternal conscious punishment (Rev 20:14-15; Matt 25:46).

Tartarus and the Abyss are specialized holding places for fallen angels and demonic powers, not the normal destinations of human souls. Hades is temporary. Gehenna is eternal. The lake of fire is Revelation’s term for what Jesus calls Gehenna. To conflate these stages is to miss the scriptural architecture. To distinguish them is to see the progression clearly: death, intermediate state, resurrection, judgment, eternal destiny.

Sleep as Metaphor: Death’s Appearance, Not Its Reality

But what of the language of sleep? Scripture frequently uses sleep to describe death. David speaks of sleeping with his fathers (1 Kings 2:10). Paul writes, “We do not want you to be uninformed, brothers, about those who are asleep, that you may not grieve as others do who have no hope” (1 Thessalonians 4:13, ESV). Stephen, as he dies under the stones, “fell asleep” (Acts 7:60, ESV). Does this language teach that the dead are unconscious, unaware, in a state of soul-sleep until the resurrection?

No. Sleep is a metaphor, not a theological description of the intermediate state. And Scripture itself demonstrates this by using sleep and death contrastively, not interchangeably. When Jesus says to the disciples, “Our friend Lazarus has fallen asleep, but I go to awaken him” (John 11:11, ESV), the disciples misunderstand and reply, “Lord, if he has fallen asleep, he will recover” (John 11:12, ESV). They think Jesus means natural sleep. So Jesus speaks plainly: “Lazarus has died” (John 11:14, ESV). Here sleep is a figure for death, but the disciples’ confusion shows that sleep and death are not the same thing. Jesus must clarify because death is not merely sleep.

Scripture uses sleep as a metaphor for death for three reasons: first, because death resembles sleep in outward appearance—the body lies still, eyes closed, motionless, awaiting awakening. Second, because for believers, death is temporary—just as sleep ends in waking, so death ends in resurrection. Paul makes this explicit when he writes of the resurrection as the moment when “the dead in Christ will rise” (1 Thessalonians 4:16, ESV), using the sleep metaphor to emphasize the certainty of awakening, not the unconsciousness of the interval. Third, because sleep softens the terror of death for those in Christ—it is rest, not annihilation; dormancy, not destruction.

But the metaphor of sleep does not negate the reality of conscious existence in the intermediate state. When Stephen is stoned, he does not fall into unconsciousness and wait in oblivion. Before the narrative says “he fell asleep,” it records his conscious prayer: “Lord Jesus, receive my spirit” (Acts 7:59, ESV). The sleep language describes his death; the prayer describes his conscious commendation of his spirit to Christ at the moment of death. When Paul contemplates his own death, he does not speak of unconscious waiting but of immediate presence with Christ: “My desire is to depart and be with Christ, for that is far better” (Philippians 1:23, ESV). To depart—analusai (ἀναλῦσαι), meaning to break camp, to set sail, to leave this life—is to be with Christ, not to enter unconscious oblivion. If death meant soul-sleep, Paul’s statement makes no sense. Why would unconsciousness be “far better” than conscious service to Christ in this life? The answer is clear: Paul expects immediate, conscious fellowship with Christ upon death.

The language of sleep is pastoral comfort, not ontological description. It assures believers that death is not the end, that the body will awaken, that separation is temporary. But it does not teach that the soul ceases to be conscious between death and resurrection. Jesus’ parable in Luke 16, Paul’s longing to be with Christ, Stephen’s prayer as he dies, the souls under the altar crying out in Revelation 6:9–10—all testify to conscious existence in the intermediate state. Sleep describes the body’s rest and the certainty of resurrection. It does not describe the soul’s condition between death and awakening.

The Resurrection: Universal, Bodily, Irreversible

But the intermediate state is not the end. Scripture insists that every human being—every one—will be raised. Jesus says explicitly, “An hour is coming when all who are in the tombs will hear his voice and come out, those who have done good to the resurrection of life, and those who have done evil to the resurrection of judgment” (John 5:28–29, ESV). This statement appears in John’s Gospel within Jesus’ discourse on His authority to judge and give life, where He claims equality with the Father and declares that the dead will hear the voice of the Son of God and live (John 5:25). The resurrection is not selective. It is universal. All will be raised—the righteous to life, the wicked to judgment.

Daniel saw the same reality in apocalyptic vision: “And many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt” (Daniel 12:2, ESV). Daniel’s vision comes at the climax of his prophecy, following the tribulation of Israel and the deliverance of God’s people, pointing forward to the final resurrection as the vindication of the righteous and the exposure of the wicked. John sees the dead, great and small, standing before the throne, with Death and Hades giving up their dead for judgment (Revelation 20:12–13). The sea, Death, and Hades surrender their captives. No one remains hidden. No one escapes. All are raised.

Why resurrect the wicked? Because judgment is not merely spiritual. Humanity sinned in the body; humanity is judged in the body. The deeds done in the body—whether good or evil—are brought into account (2 Corinthians 5:10). Why resurrect the righteous? Because salvation is not escape from creation but the renewal of creation. The New Heavens and New Earth are not ethereal clouds but a restored cosmos, a redeemed Eden, a world where death is no more and the curse is undone (Revelation 21:1–4). Resurrection is the necessary precondition for both eternal punishment and eternal life because both destinies are embodied destinies. We do not float as disembodied spirits for eternity. We are raised, body and soul reunited, to face judgment and enter our eternal state.

The Final Judgment: Public, Righteous, Eternal

After resurrection comes judgment—final, public, irreversible. Christ is the Judge. The Father “has given all judgment to the Son” (John 5:22, ESV). Truth is the standard. Every secret thing will be brought to light (Ecclesiastes 12:14). Works are the evidence. “The dead were judged by what was written in the books, according to what they had done” (Revelation 20:12, ESV). Eternity is the outcome. And Scripture gives only two outcomes: eternal life in the presence of God or eternal punishment in the lake of fire, the second death (Matthew 25:46; Revelation 20:14–15).

Here the question presses hardest: Is the second death conscious? Scripture’s answer is unflinching. The Beast, the False Prophet, and the Devil are cast into the lake of fire where “they will be tormented day and night forever and ever” (Revelation 20:10, ESV). The wicked share the same destination: “If anyone’s name was not found written in the book of life, he was thrown into the lake of fire” (Revelation 20:15, ESV). Jesus describes the final judgment as a place of weeping and gnashing of teeth—not the silence of non-existence but the agony of regret, rebellion, and ruin (Matthew 25:30). Paul calls it “eternal destruction, away from the presence of the Lord and from the glory of his might” (2 Thessalonians 1:9, ESV). Paul writes this to the Thessalonians in the context of Christ’s return in flaming fire, bringing vengeance on those who do not know God and do not obey the gospel—a destruction that is not cessation but everlasting separation.

The Greek term for destruction—apo̅leia (ἀπώλεια)—does not mean annihilation. It means ruin, loss, separation from God’s saving purposes. When a wineskin is destroyed, it does not cease to exist; it becomes useless for its intended purpose (Matthew 9:17). When the son in the parable is lost—apollumi (ἀπόλλυμι), the verbal form—he is not annihilated; he is separated from the father’s house, ruined, in a far country feeding pigs (Luke 15:13–17). The word denotes not cessation of existence but the loss of everything that makes existence good.

Why call it “death” if it is conscious? Because in Scripture, death is not primarily the cessation of existence but the rupture of relationship. Physical death is the separation of body and soul (James 2:26). Spiritual death is the separation of the sinner from God’s life (Ephesians 2:1). The second death is the final, irreversible separation from God’s goodness, mercy, and presence. It is called death because it is the ultimate expression of alienation from the source of all life. But it is not unconsciousness. It is conscious exclusion from the only source of joy.

Abraham’s Role: Covenant Witness, Not Afterlife Manager

And why does Jesus place Abraham in the parable? Because Abraham is the covenant father, the one whose name the rich man invokes as a shield. “Father Abraham, have mercy on me,” he cries (Luke 16:24, ESV), as if lineage could save him. Abraham’s presence exposes the lie. Covenant privilege without covenant faith is no refuge. Physical descent from Abraham counts for nothing if the heart remains impenitent. John the Baptist warned the Pharisees and Sadducees of this very danger: “Do not presume to say to yourselves, ‘We have Abraham as our father,’ for I tell you, God is able from these stones to raise up children for Abraham” (Matthew 3:9, ESV).

Abraham becomes the perfect narrative voice to deliver the devastating line: “They have Moses and the Prophets; let them hear them” (Luke 16:29, ESV). The rich man had the Scriptures. He had the Law. He had the Prophets. He had every warning, every call to repentance, every promise of judgment. And he ignored them. Now he wants a miracle—a resurrection, a supernatural sign, a warning from beyond the grave. Abraham refuses. “If they do not hear Moses and the Prophets, neither will they be convinced if someone should rise from the dead” (Luke 16:31, ESV). The parable is not teaching that Abraham manages the afterlife or that the righteous and wicked literally converse across a chasm. Jesus is using real afterlife categories—consciousness, comfort, torment, fixed destinies—arranged in a story form to expose the danger of presumption and the sufficiency of Scripture.

The Sufficiency of Scripture: Resurrection Is Not Enough

And the final line is the sharpest: “If they do not hear Moses and the Prophets, neither will they be convinced if someone should rise from the dead” (Luke 16:31, ESV). Someone did rise. Jesus told this parable, and then He died, and then He rose from the dead on the third day, just as the Scriptures foretold (1 Corinthians 15:3–4). He appeared to the apostles, to more than five hundred witnesses, to James, to Paul (1 Corinthians 15:5–8). The resurrection happened. And still, many are not convinced. The religious leaders who demanded His crucifixion heard the testimony of the guards at the tomb and chose to bribe them into silence (Matthew 28:11–15). The Pharisees who saw Lazarus raised from the dead plotted to kill both Jesus and Lazarus (John 11:53; 12:10). Miracles do not soften hard hearts. Resurrection does not create faith where Scripture has been rejected.

This is why the parable ends where it does. The rich man wanted a warning sent. Abraham said Scripture was enough. Jesus told the story, rose from the dead, and proved Abraham right. The problem is not a lack of evidence. The problem is a refusal to hear what God has already spoken.

It is about eternal separation

“Between us and you a great chasm has been fixed, in order that those who would pass from here to you may not be able, and none may cross from there to us.” (Luke 16:26, ESV)

—Luke 16:31, ESV

Abraham’s answer to the rich man is final. The chasm is fixed. No one crosses. No warnings will be sent. No miracles will be performed. “They have Moses and the Prophets; let them hear them” (Luke 16:29, ESV). The rich man had the Scriptures in life. He ignored them. Now he wants resurrection, supernatural intervention, a sign from beyond the grave to convince his brothers. Abraham refuses: “If they do not hear Moses and the Prophets, neither will they be convinced if someone should rise from the dead”

Someone did rise. Jesus told this parable, and then He died, and then He rose from the dead on the third day, just as the Scriptures foretold (1 Corinthians 15:3–4). The resurrection happened. And still, many are not convinced. The religious leaders who demanded His crucifixion heard the testimony and chose to suppress it (Matthew 28:11–15). The Pharisees who saw Lazarus raised plotted to kill both Jesus and Lazarus (John 11:53; 12:10). Miracles do not soften hard hearts. Resurrection does not create faith where Scripture has been rejected.

And now we stand where the rich man’s brothers stood—alive, warned, confronted by the same Scriptures, addressed by the same Christ who told the story and then rose from the dead. The parable is not about wealth and poverty. It is not about social justice. It is not about topography. It is about eternal separation. It is about conscious existence after death. It is about the fixed chasm between the elect and the non-elect, between those at Abraham’s side and those in torment, between Paradise and Hades.

The intermediate state is real. The separation is conscious. The destinies are irreversible. The resurrection is coming. The judgment is certain. And the final state—either eternal life in the New Heavens and New Earth or eternal punishment in the lake of fire—is embodied, conscious, and everlasting.

“And in Hades, being in torment, he lifted up his eyes and saw Abraham far off and Lazarus at his side” (Luke 16:23, ESV). Two men, both dead, both conscious, eternally divided. One in comfort. One in torment. Both awaiting the resurrection. Both facing the final judgment.

The question is not whether we will die. The question is not whether we will be conscious after death. The question is where we will be when we lift our eyes—and whether we will have heard Moses and the Prophets, and Christ, before the chasm is fixed.

Editor’s Note: If you have read this article and still regard the intermediate state, the resurrection of the body, and the conscious eternal destinies as mythological speculation or theological invention, then perhaps the problem is not the evidence but the heart that receives it. Jesus Himself said in this very parable, “If they do not hear Moses and the Prophets, neither will they be convinced if someone should rise from the dead” (Luke 16:31, ESV). No amount of biblical exposition, no marshaling of Scripture texts, no careful exegesis will persuade a heart hardened against God’s revelation. The issue is not intellectual but spiritual—not lack of proof but refusal to see, inability to hear, resistance to what God has plainly spoken.

But if you are someone of faith—if you trust God’s Word as Abraham trusted God’s promise—and you find yourself uncertain or unfamiliar with these doctrines because you have not had much teaching on eschatology, death, and the afterlife, I encourage you not to take our word for any of this. Study the passages listed below in their full context. Read the chapters surrounding each verse. Trace the themes through the canon. Let Scripture interpret Scripture. Pray, ask the Spirit to illuminate what God has revealed. The doctrine of last things is not reserved for theologians or academics. It is given to the church, to every believer, so that we might live with urgency, hope, and clarity about where we are going and why we must hear Christ before we die.

The chasm is real. The judgment is certain. The destinies are eternal. And the Scriptures are sufficient.

SCRIPTURE REFERENCES USED IN THIS ARTICLE (in order of appearance)

Luke 16:19–31 (primary text—parable of the rich man and Lazarus)

- Luke 16:19–21 (backstory: rich man and Lazarus in life)

- Luke 16:22 (both men die)

- Luke 16:23–24 (rich man in Hades, Lazarus at Abraham’s side)

- Luke 16:26 (great chasm fixed)

- Luke 16:28 (rich man’s five brothers)

- Luke 16:29 (“They have Moses and the Prophets”)

- Luke 16:31 (“If they do not hear Moses and the Prophets…”)

Revelation 20:14–15 (lake of fire, second death)

Revelation 21:1–4 (New Heavens and New Earth)

John 13:23 (beloved disciple at Jesus’ chest)

Hebrews 9:27 (appointed to die once, then judgment)

Luke 15:11–32 (prodigal son parable)

Genesis 2:7 (Adam became a living soul)

Genesis 35:18 (Rachel’s soul departing)

James 2:26 (body apart from spirit is dead)

Genesis 3:19 (dust to dust)

Ecclesiastes 12:7 (spirit returns to God)

Luke 23:43 (today you will be with me in Paradise)

Acts 7:59 (Stephen: “Lord Jesus, receive my spirit”)

2 Corinthians 5:8 (away from body, at home with the Lord)

Philippians 1:23 (desire to depart and be with Christ)

1 Thessalonians 4:16 (the dead in Christ will rise)

1 Corinthians 15:42–44 (resurrection body: imperishable, glorious, spiritual)

Matthew 10:28 (fear Him who can destroy both soul and body in hell)

Revelation 20:13–15 (final judgment, lake of fire)

Romans 8:23 (redemption of our bodies)

1 Corinthians 15:54 (death swallowed up in victory)

Genesis 37:35 (Jacob: go down to Sheol)

1 Samuel 2:6 (the Lord brings down to Sheol and raises up)

Psalm 86:13 (deliverance from Sheol)

Isaiah 14:9 (Sheol stirred up to meet the king of Babylon)

Job 14:13 (Sheol as hiding place)

Matthew 16:18 (gates of Hades will not prevail)

Matthew 11:23; Luke 10:15 (Capernaum brought down to Hades)

Acts 2:27, 31 (God did not abandon Christ’s soul to Hades)

Revelation 6:8 (Death and Hades as riders)

Revelation 20:13–14 (Death and Hades give up the dead, thrown into lake of fire)

2 Corinthians 12:3–4 (Paul caught up to Paradise)

Revelation 2:7 (tree of life in the paradise of God)

Mark 9:43–48 (Gehenna: worm does not die, fire not quenched)

Matthew 23:15 (sons of Gehenna)

Matthew 5:22 (liable to the hell of fire—Gehenna)

2 Kings 23:10; Jeremiah 7:31 (Valley of Hinnom, child sacrifices to Molech)

Matthew 25:41 (eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels)

Revelation 19:20 (Beast and False Prophet thrown into lake of fire)

Revelation 20:10 (Devil tormented day and night forever and ever)

Revelation 21:8 (cowardly, faithless, etc.—portion in the lake of fire)

2 Peter 2:4 (angels cast into Tartarus)

Jude 6 (angels kept in eternal chains under gloomy darkness)

Luke 8:31 (demons beg not to be sent to the abyss)

Romans 10:7 (who will descend into the abyss?)

Revelation 11:7; 17:8 (beast ascends from the abyss)

Revelation 20:1–3 (Satan cast into the abyss for a thousand years)

Revelation 9:1–11 (demonic locusts from the abyss)

Isaiah 65:17; 66:22 (new heavens and new earth prophesied)

2 Peter 3:13 (new heavens and new earth in which righteousness dwells)

Revelation 21:1 (new heaven and new earth)

Revelation 21:2 (New Jerusalem descends)

Revelation 22:2 (tree of life with twelve kinds of fruit)

Revelation 22:3–4 (no more curse, worship face to face)

1 Kings 2:10 (David slept with his fathers)

1 Thessalonians 4:13 (those who are asleep)

Acts 7:60 (Stephen fell asleep)

John 11:11 (Lazarus has fallen asleep)

John 11:12 (disciples: if he has fallen asleep, he will recover)

John 11:14 (Lazarus has died)

Revelation 6:9–10 (souls under the altar crying out)

John 5:28–29 (all in tombs will hear His voice and come out)

John 5:25 (the dead will hear the voice of the Son of God)

Daniel 12:2 (many who sleep shall awake, some to everlasting life, some to shame)

Revelation 20:12–13 (the dead judged by what was written in the books)

2 Corinthians 5:10 (deeds done in the body)

John 5:22 (Father has given all judgment to the Son)

Ecclesiastes 12:14 (every secret thing brought to light)

Matthew 25:46 (eternal punishment vs. eternal life)

Matthew 25:30 (weeping and gnashing of teeth)

2 Thessalonians 1:9 (eternal destruction, away from the presence of the Lord)

Matthew 9:17 (wineskins destroyed)

Luke 15:13–17 (prodigal son lost/ruined)

Ephesians 2:1 (dead in trespasses and sins)

Matthew 3:9 (God able to raise up children for Abraham from stones)

1 Corinthians 15:3–4 (Christ died, buried, raised on the third day)

1 Corinthians 15:5–8 (resurrection appearances)

Matthew 28:11–15 (guards bribed to lie about resurrection)

John 11:53 (Pharisees plotted to kill Jesus)

John 12:10 (chief priests plotted to kill Lazarus)