Altering the Course of Divine Judgment.

God’s holiness does not change, but His dealings with repentance does—because mercy is as much a part of His nature as justice. Repentance changes our standing before God, but it does not always remove the ripple effects of sin.

Holiness, Sin, and the Mercy That Withholds Judgment

“When God saw what they did, how they turned from their evil way, God relented of the disaster that he had said he would do to them, and he did not do it.”

— Jonah 3:10, ESV

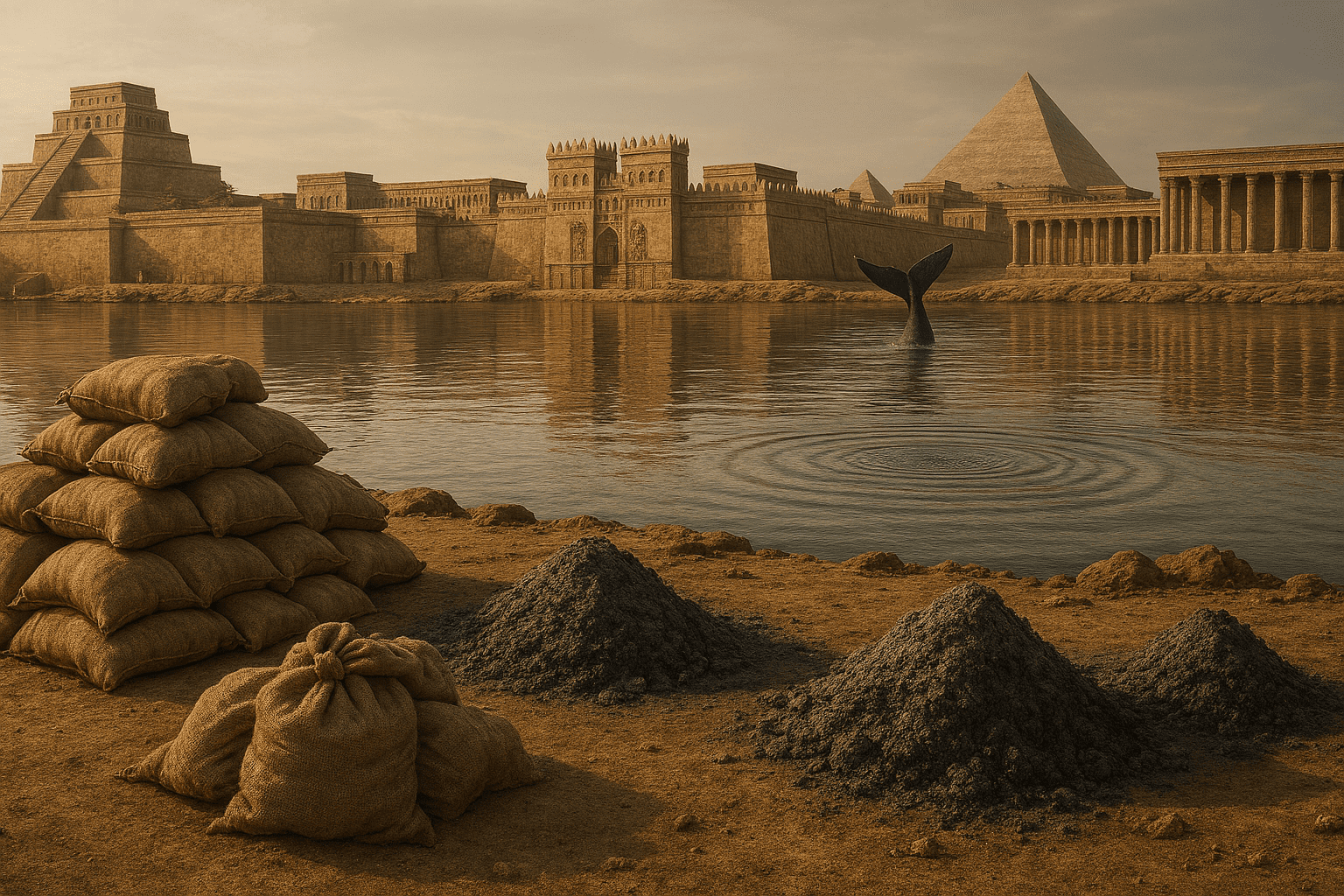

The streets of Nineveh were still. Sackcloth rustled in the wind. Ash clung to the foreheads of the mighty and the lowly alike. The king had stepped down from his throne, his royal robe replaced with the coarse fabric of mourning. From the palace to the marketplace, the city had turned from violence to pleading. Jonah’s voice had long since faded from the air, but the weight of his warning lingered. And then—God saw.

The God Who Is Holy

The God who saw Nineveh is the God Isaiah saw in the temple, high and lifted up, the train of His robe filling the sanctuary, seraphim crying to one another, “Holy, holy, holy is the LORD of hosts; the whole earth is full of his glory!” (Isaiah 6:3, ESV). Holiness is not an ornament to His nature; it is His very essence. It is the blazing purity that cannot look upon evil with approval, the moral perfection that exposes every shadow.

Nineveh’s cruelty, idolatry, and oppression had risen before Him, demanding justice. The Assyrian empire was infamous for its brutality—public executions, impalements, and the crushing of weaker nations. God’s holiness could not ignore such evil. His justice is not arbitrary; it is the necessary expression of His perfect character.

Yet holiness is not sterile detachment. The same fire that consumes sin also burns with love for the sinner. This is why God sends warnings before judgment. His holiness is not only retributive—it is redemptive. He is “merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness” (Exodus 34:6, ESV), even toward those who have provoked His wrath.

The People Who Are Sinful

From Eden onward, humanity has been bent toward rebellion. Paul’s verdict is universal: “For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23, ESV). Nineveh’s sin was notorious, but not unique. Pride, greed, violence, and deceit are not confined to ancient Assyria—they are the native language of fallen hearts.

The prophets often spoke of Israel’s sins in the same breath as the nations’. Amos condemned Damascus, Gaza, Tyre, Edom, and Ammon—but he also turned his gaze on Judah and Israel (Amos 1–2). The point is clear: no people, no matter their heritage or privilege, can stand before God’s holiness on their own merit.

Nineveh’s guilt was undeniable. But guilt is not the end of the story when God is the one writing it.

The Warning That Is Mercy

Jonah’s cry—“Yet forty days, and Nineveh shall be overthrown!” (Jonah 3:4, ESV)—was not an immutable decree carved in stone. It was a conditional warning, consistent with God’s own stated pattern: “If at any time I declare concerning a nation… that I will pluck up and break down and destroy it, and if that nation… turns from its evil, I will relent of the disaster that I intended to do to it” (Jeremiah 18:7–8, ESV).

The warning itself was mercy. God could have destroyed Nineveh without a word, as He did Sodom and Gomorrah. Instead, He sent a prophet—reluctant though Jonah was—giving space for repentance. Every prophetic warning in Scripture is an act of grace, a divine invitation to turn before it is too late.

The Repentance That God Sees

Nineveh’s response was immediate and total: “And the people of Nineveh believed God. They called for a fast and put on sackcloth, from the greatest of them to the least of them” (Jonah 3:5, ESV). The king himself stepped down from his throne, covered himself in sackcloth, and sat in ashes. His decree called for everyone—even the animals—to fast and cry out to God, turning from violence and evil.

This was not a superficial performance. The text emphasizes their turning “from their evil way” (v. 10). Repentance in Scripture is never merely emotional sorrow; it is a decisive change of direction. As Joel would later exhort, “Rend your hearts and not your garments” (Joel 2:13, ESV).

And then comes the hinge: “When God saw what they did… God relented of the disaster… and he did not do it” (Jonah 3:10, ESV). The “when He saw” is not a revelation to God—He knew their repentance before it happened. It is a narrative marker for us, showing that God’s mercy is not abstract. It is applied in real time to real people who turn to Him.

Echoes Throughout Scripture

Nineveh’s story is not an isolated event. When Hezekiah lay sick and near death, he turned his face to the wall and prayed, weeping bitterly. God’s word came through Isaiah: “I have heard your prayer; I have seen your tears. Behold, I will heal you” (2 Kings 20:5, ESV).

When Ahab, one of Israel’s most corrupt kings, tore his clothes and fasted after Elijah’s rebuke, the Lord said, “Because he has humbled himself before me, I will not bring the disaster in his days” (1 Kings 21:29, ESV).

Even Manasseh, who had filled Jerusalem with idolatry and bloodshed, found mercy when he humbled himself greatly before the God of his fathers in captivity; God brought him back to Jerusalem and restored his kingdom (2 Chronicles 33:12–13).

In each case, repentance altered the course of judgment. God’s holiness did not change, but His dealings with the repentant did—because mercy is as much a part of His nature as justice.

Mercy and the Consequences That Remain

Repentance changes our standing before God, but it does not always remove the ripple effects of sin. David was forgiven for his sin with Bathsheba—“The LORD also has put away your sin; you shall not die” (2 Samuel 12:13, ESV)—yet Nathan told him, “The sword shall never depart from your house” (v. 10).

This is not God being vindictive. It is the reality of a moral universe. Choices have consequences. Trust broken takes time to rebuild. Wounds inflicted may leave scars. But grace means those scars are no longer signs of condemnation; they become testimonies of redemption.

Grace That Is Sufficient

Paul’s thorn in the flesh was not removed despite his prayers, but God told him, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness” (2 Corinthians 12:9, ESV). Grace is not merely pardon; it is sustaining power. It is what carried the Ninevites forward after their reprieve. It is what carried David through family turmoil. It is what carries us when the consequences of past sin still echo in our lives.

The Cross: Where Holiness and Mercy Meet

All these moments point to the cross, where holiness and mercy meet perfectly. God’s judgment against sin fell on Jesus, so that mercy could flow to us without compromising holiness: “For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God” (2 Corinthians 5:21, ESV).

At Calvary, God did not merely relent from judgment—He satisfied justice and extended mercy in one act. The cross is the ultimate “when God saw,” the moment when the repentance of sinners meets the provision of a Savior.

The God Who Still Sees

And so we return to Nineveh. The sackcloth still clung to skin, the ashes still marked foreheads, but the air was different. The fear of impending ruin had given way to the relief of mercy received. The same God still sees. He sees the turning of a heart, the humbling of a will, the cry for mercy. His holiness has not diminished, and neither has His readiness to forgive.

“When God saw what they did, how they turned from their evil way, God relented of the disaster that he had said he would do to them, and he did not do it.”

— Jonah 3:10, ESV

The city of Nineveh stands as a witness: judgment can be withheld, grace can be given, and the God who sees is the God who saves.

Editor’s Note: Our hope is that we addressed how God’s unchanging character expresses itself through His responsive mercy. “When God sees” reveals the beautiful truth of divine sovereignty—not as cold determinism, but as covenantal love that operates according to God’s eternal nature.

God’s sovereignty isn’t mechanical or impersonal—it’s covenantal and responsive. The threat against Nineveh wasn’t an immutable decree carved in stone, but a conditional warning that perfectly aligns with God’s revealed character in Jeremiah 18:7-10.

When Nineveh repented, God didn’t change His eternal will—He enacted what was always consistent with His nature: mercy meeting genuine repentance.

This has immediate application for every believer. Connecting Nineveh’s story to our ongoing sanctification. Holiness isn’t a destination we reach this side of eternity—it’s the daily discipline of stopping, turning around, and walking worthy of our great salvation. Like the Ninevites, we’re called to ongoing repentance, not as defeated Christians, but as those progressively transformed by grace.

If you are wrestling with past failures or present struggles, you will find hope in a God whose sovereignty includes foreknown contingencies—a God who delights in mercy and responds to the turning heart. This isn’t cheap grace; it’s costly grace that calls us to genuine transformation while assuring us that our God sees, responds, and saves.

A timely reminder that our God’s heart beats with mercy toward the repentant.