Whose Name..?

Not just religious giving—it was for the national infrastructure. The tithe funded worship, welfare, and judicial oversight. It was the economic engine of the covenant community. But is it a prescribed new covenant number?

Rethinking Tithes and Giving in the Kingdom of Grace

“Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.”

Matthew 22:21, ESV

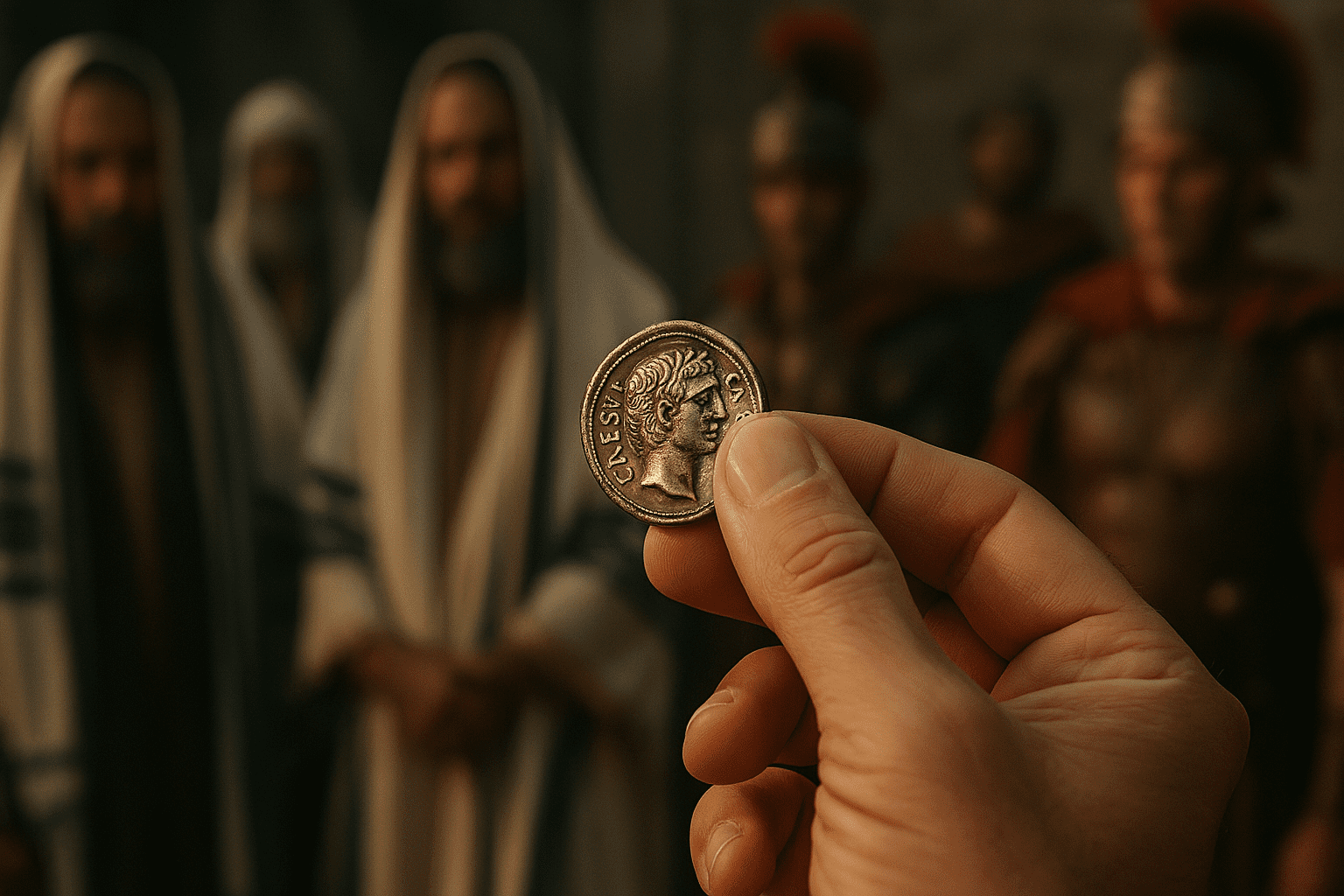

The coin glinted in the sunlight, stamped with Caesar’s image. A trap had been set. The Pharisees, joined by Herodians, asked Jesus whether it was lawful to pay taxes to Rome. If He said yes, He’d alienate the Jewish nationalists. If He said no, He’d be branded a rebel. But Jesus didn’t take the bait. Instead, He asked for a coin, pointed to the image, and delivered a reply that still reverberates: “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.”

It was more than a clever dodge. It was a redefinition of allegiance. In one sentence, Jesus separated civic obligation from divine devotion. But what, exactly, belongs to God? And how does that shape our understanding of giving in the New Covenant?

To answer that, we must first understand the tithe—not as a spiritual metaphor, but as a civic mechanism embedded in Israel’s theocratic system. Only then can we grasp the radical shift Jesus inaugurated: from taxation under law to generosity under grace.

Theocratic Infrastructure and the Levitical Economy

- Leviticus 27:30–32 — “Every tithe of the land… is holy to the Lord.”

- Numbers 18:21–24 — “To the Levites I have given every tithe… as their inheritance.”

- Deuteronomy 14:22–29 — Instructions for annual and third-year tithes.

- 2 Chronicles 31:5–6 — Hezekiah’s reforms and tithe restoration.

In ancient Israel, the tithe was not merely a spiritual discipline—it was a national tax. The Mosaic covenant established a theocracy, where God was king and the Levites functioned as civil servants. They maintained the tabernacle, taught the law, and adjudicated disputes. But unlike the other tribes, the Levites received no land inheritance. Their sustenance came from the tithe.

This wasn’t just religious giving—it was national infrastructure. The tithe funded worship, welfare, and judicial oversight. It was the economic engine of the covenant community.

Malachi’s Rebuke and the Collapse of Covenant

Malachi 3:8–10 — “Will man rob God? Yet you are robbing me… Bring the full tithe into the storehouse.”

By the time of Malachi, the system was faltering. The temple had been rebuilt after exile, but the people were apathetic. Priests were corrupt. Sacrifices were blemished. And the tithe was neglected.

The accusation is not metaphorical. Withholding the tithe meant starving the Levites, abandoning the poor, and dishonoring the covenant. The rebuke is sharp because the stakes are high: the entire theocratic structure depended on faithful giving.

Malachi offers a promise—but it’s covenantal, not commercial. The tithe was the hinge of national obedience. Without it, the system collapsed.

Jesus’ Kingdom and the Absence of Civic Mandate

- John 18:36 — “My kingdom is not of this world.”

- Luke 21:1–4 — The widow’s offering: “She… put in more than all of them.”

- Matthew 23:23 — “You tithe mint and dill… but neglect justice, mercy, and faithfulness.”

Jesus never commands a tithe. He praises the widow who gives two small coins—not for the amount, but for the heart behind it. He warns against Pharisees who tithe herbs but neglect weightier matters. His emphasis is always on posture, not percentage.

His kingdom has no tax code, no priestly caste, no temple bureaucracy. It is a spiritual reign—one that transforms hearts, not governments.

Typological Fulfillment and the End of the Levitical System

- Hebrews 7:4–9 — “Consider how great this man was… Melchizedek received tithes from Abraham.”

- Hebrews 8:13 — “In speaking of a new covenant, he makes the first one obsolete.”

The tithe pointed forward. It sustained a priesthood that mediated between God and man. But in Christ, that mediation is fulfilled. He is the final priest, the final sacrifice, the final temple.

Hebrews draws the typological thread tight. Jesus, like Melchizedek, receives a better offering—not grain, but lives. The old covenant is set aside, and with it, the civic structures that required taxation. What remains is the call to generosity—not as law, but as love.

Paul’s Theology of Giving and the Grace of Overflow

- 2 Corinthians 8:3–5 — “They gave beyond their means… first to the Lord.”

- 2 Corinthians 8:9 — “Though He was rich, yet for your sake He became poor.”

- 2 Corinthians 9:6–7 — “Each one must give… not reluctantly or under compulsion.”

- Philippians 4:18 — “A fragrant offering, a sacrifice acceptable and pleasing to God.”

Paul never commands a tithe. Instead, he builds a theology of giving rooted in grace. The Macedonians gave sacrificially—not because they had much, but because they had been transformed.

Giving becomes a reflection of Christ’s self-emptying love. The harvest is not wealth—it’s righteousness. The goal is not accumulation, but abundance—for others.

Giving as Formation, Not Obligation

- Romans 12:1 — “Present your bodies as a living sacrifice.”

- Acts 2:44–45 — “They had all things in common… as any had need.”

In the New Covenant, giving is not about funding a government. It’s about forming a people. It’s not about percentages—it’s about posture. The church is not sustained by taxes, but by grace. And grace, when truly received, overflows.

Giving is essential—but in a different way. It’s not enforced by statute, but provoked by salvation. It’s not calculated—it’s consecrated.

The Circle Closes on the Coin

- Genesis 1:27 — “So God created man in His own image.”

- Matthew 22:21 — “Render… to God the things that are God’s.”

The coin bore Caesar’s image. But humans bear God’s. When Jesus said, “Render to God the things that are God’s,” He wasn’t just talking about money. He was talking about everything.

Imagine a believer holding a coin—not asking “how much must I give?” but “how deeply can I surrender?” The question shifts from percentage to posture, from law to love.

In the Old Covenant, giving was about sustaining a nation. In the New Covenant, it’s about surrendering to a kingdom. The tithe was a tax. Giving is a treasure.

And so the circle closes. The trap set by the Pharisees becomes a doorway to deeper truth. In the kingdom of grace, the question is no longer “How much must I give?” but “How much can I offer?”

Because in this kingdom, giving is no longer a tenth—it’s a testimony. Paul captures this transformation perfectly: ‘Each one must give as he has decided in his heart, not reluctantly or under compulsion, for God loves a cheerful giver’ (2 Corinthians 9:7). The Macedonians exemplified this—they gave ‘beyond their means’ not because of a percentage requirement, but because they had ‘first given themselves to the Lord’ (2 Corinthians 8:3,5). Their generosity testified to Christ’s transforming work in their hearts.

Editor’s Note: Some readers may wonder about Abraham’s tithe to Melchizedek (Genesis 14:20) and the judgment of Ananias and Sapphira (Acts 5:1-11).

Abraham’s tithe was a one-time act of gratitude following military victory, not an established pattern.

The Ananias and Sapphira incident actually supports this article’s thesis—Peter explicitly states “while it remained unsold, did it not remain your own? And after it was sold, was it not at your disposal?” (Acts 5:4). Their sin wasn’t failing to give a prescribed amount, but lying about their voluntary gift. This confirms that New Covenant giving is voluntary, heart-motivated, and without fixed percentages—making deception about one’s generosity all the more grievous because it corrupts the very nature of grace-based giving.